BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

For John Bross, the first day of spring was to be celebrated.

It would begin with taking the winter wreath bearing lemons off the front door and then going to the front yard to look for his favorite flower, the vibrant blue Scilla siberica that springs up in the cold. He would then take a walk to Lincoln Park from our home in nearby Old Town.

Photo by Mike Traynor.

For the last six months he has not been able to walk to his beloved park due to an aggressive form of brain cancer known as glioblastoma. I choose to go along with those who believe that at the end we have a little say in our final departure. Winter ended at 10 pm on March 19th—a day earlier than the usual March 20 because it is leap year—and my husband, John, died peacefully in his sleep at 11:15 pm, filled with faith and his cat Sedgwick, as always throughout the illness right at his side.

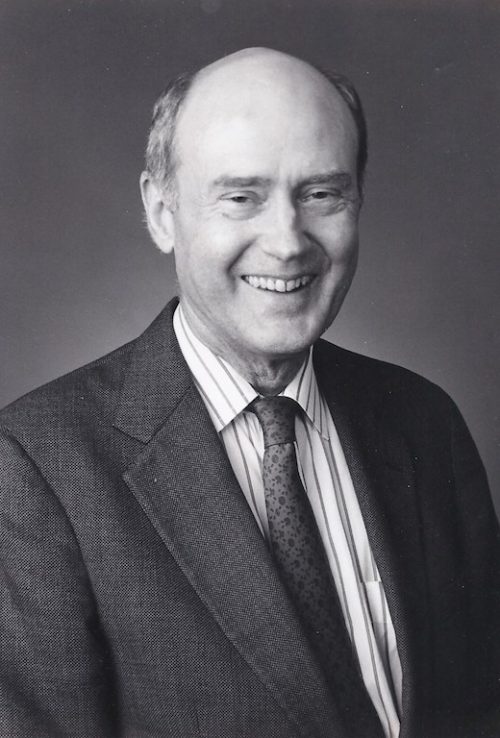

Photo courtesy of Northern Trust.

During these days of social distancing when there can be no celebratory memorial services or any gatherings of family and friends to swap lovely memories, many have showed love in inventive ways. If you are also dealing with a loss and you can’t reach out to a family in person, your love will find ways to be present: more phone calls, more emails, more letters are so welcome by grieving families who cannot hug you at this time. Some friends on a daily dog walk have come by to wave through the window.

John, had more friends than just about anyone due to his empathy, marvelous conversation, delightful wit, a desire to know all about you, and faith beyond measure. His close friend Mike Traynor walked through Lincoln Park in the days before John died, facetiming with him about the blue heron on the pond, the first blooms of spring in little gardens (such as the one named for David M. McKay, with rocks bearing Shakespeare sonnets), and a friendly squirrel perhaps missing human attention. He then sent the photos to John of the new life he was observing.

Photo by Mike Traynor.

Photo by Mike Traynor.

Photo by Mike Traynor.

John loved the statue of General Grant in Lincoln Park and its soaring base designed by a Chicago architect. As an author and authority on the Civil War, he loved the fact that over 100,000 people contributed to the funding of the bronze monument, and that Mrs. Grant was there for the dedication.

In 2018 John published Letters to Belle: Civil War Letters and Life of Chicago Lawyer and Volunteer Colonel John A. Bross, 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, about the intersection between the Civil War, Chicago, and his own ancestors. The book, which was the subject of the Annual Meeting of the Chicago History Museum and presented to other groups including the Society of Colonial Warriors in the State of Illinois, is a collaboration between John and his sister Justine Bross Yildiz.

Originally a project begun to share this family story with his grandchildren, it evolved into a book that John researched and wrote with great dedication. His hope was that the result does “what history should always do: namely, open our eyes to the past and give us a better understanding of where we came from and why and how we have become what we are.”

The book is divided into two sections, with one devoted to the almost 90 letters that Justine had in her possession, handed down over generations, written by their ancestor John Armstrong Bross to his wife, Belle (Isabella). In John’s words: “Some of these letters tell the story of battles or of the mundane day-to-day life of a soldier, but they all paint a picture of a devoted Chicago husband and father.” The other portion of the book provides a background on John Armstrong Bross and Chicago at that time, and an astute look into the Civil War and its battles, turning points, and lasting legacies.

John’s great-grandfather, originally from New York, was a successful lawyer and active member of the Third Presbyterian Church here in Chicago. He wed Isabella Mason in 1856, and the couple had a little girl, Cora, who died as a child, and a son, Mason. John was politically active, just like his older brother William, Illinois’s 16th Lieutenant Governor, who with Joseph Medill, was a principal owner of the Tribune.

John volunteered for service in the Civil War in 1862, age 36, raising two companies for the 88th Illinois Regiment and enlisting as captain of one of them. During his service, he participated in the Battle of Perryville (Kentucky), Murfreesboro (Tennessee), and the Battle of Chickamauga (Tennessee/Georgia). Following the latter, John was named by the Governor of Illinois to raise a regiment of African-American soldiers in Illinois. He left Tennessee and went back to begin recruiting in Quincy, Illinois. John’s 29th Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops (now 29th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry), joined General Grant and his army in Virginia.

John Armstrong Bross was shot down in the devastating Battle of the Crater, part of Grant’s siege of Petersburg, July 30, 1864. Of John, one of his men, Private Willis Bogart, wrote his widow, Belle, this: “I found in Colonel Bross a friend, one in whom every member of the regiment placed the utmost confidence, for, and with whom, each one would help defend the country to the end. Yes, I can say with truth, they would willingly die by his side. . . . He was loved by everyone, because he was a friend to every one.”

This present-day John Bross too loved his family: daughters Suzette Bulley, Lisette Bross, and Dolly Geary; son Jonathan; and his stepchildren George York, Charlotte Matthews, and Alice York; as well as sisters Wendy Frazier and Justine Yildez, and his brother Dr. Peter Bross. Each of his 12 grandchildren—Lucy, Daphne, and Allan Bulley; Parker and Avery Bross; Addison Bross-Caccioli; Eloise and Hilary Geary; Oliver and Henry York; and Colin and Clara Matthews—has extraordinary memories of their grandfar’s creativity.

A photo of us captured by his daughter Suzette Bross Bulley.

John in Murray Bay, captured by Lisette Bross.

They loved learning from him in Chicago; on vacations in national parks; and in Murray Bay, Quebec, Canada, where we spent summers on the St. Lawrence River, camping, hiking, whale-watching, and hearing him lead us all in singing “Shall We Gather By the River.” For the latter, he would accompany on the harmonica, standing on the beach below his beloved Murray Bay Protestant Church, where he was a Trustee, delighting the children as they roasted s’mores and collected sea glass.

His volunteer life stretched from Quebec to Chiapas, Mexico, where for 12 years he was a mission volunteer to two Episcopal congregations, one in the mountainous Mayan village of Yochib. With fellow volunteers from St. Chrysostom’s Church, Church of Our Savior, and others, he participated in services, advised elders, and taught games and English classes. Señor Mateo, the wise senior statesman of that community, told John that those classes were what the community really wanted, and John funded weekly classes with great pleasure for the last eight years.

Listing all the ways his volunteer spirit and effective leadership were put to work in Chicago would fill these pages. They appear in his obituaries as a testimony to his service. As a young lawyer, then trust officer at the Northern Trust Company, he and his first wife, Louise Smith Bross, began volunteering at the Art Institute of Chicago, where they started the first Auxiliary Board in the country. His involvement with the Art Institute remained active until his death.

Early on, John committed himself to the Chicago Area Project, where he was a board member for over 50 years, championing its projects for inner city youths. He once had a birthday party where he and lots of friends painted one of their centers along with the kids who used the center on a daily basis.

At St. James Cathedral, Bexley Seabury Seminary, where he received a degree following retirement; the University of Chicago; The Shirley Ryan AbilityLab: Facets: Bishop Anderson House: the Admiral at the Lake; and many more, John was the type of volunteer every board wants: a fully involved participant and an ambassador for that group within the community. No one was a better connector, forever thinking of ways to bring individuals and organizations together for the common good.

In December, the Great Lakes Dredge Society and Philharmonic, the men’s singing group that performs during the holidays for hospitals and other groups, came to our house to serenade John, a long time chairman. After quietly joining in as they sang “Bless This House,” John told them that a brain tumor was not so bad if he could have friends come and do such a wonderful thing. That was John. As was said about his great-grandfather before him, “He was loved by everyone because he was a friend to everyone.”

At this most serious time, due to shelter-in-place protocol, you may not be able to walk among the bursting signs of spring as John could not, but like John, we must always keep spring in our hearts. And so I close with this poem, written by the unintimidatable Emily Dickinson, a favorite of John’s, recalling the busyness of the hummingbird and the awakening of all life this time of year:

A Route of Evanescence,

With a revolving Wheel—

A Resonance of Emerald

A Rush of Cochineal—

And every Blossom on the Bush

Adjusts it’s tumbled Head—

The Mail from Tunis—probably,

An easy Morning’s Ride—