By Francesco Bianchini

I am not assailed by homesickness as soon as I set foot in another country. That said, I can conjure some pleasant memories in which an unexpected air of home enveloped me, as in a time bubble, as I traveled in distant lands. Once while traveling through the desolate slate-blue peaks of Snowdonia, and having stopped in a wayside inn merely to beg the use of the toilet, I suddenly smelled an authentically piquant bolognese sauce wafting from the kitchen. Odd, as the owners turned out to be from South Korea. We stayed for lunch.

‘Little Italy’ in Manhattan is now nothing more than an appendage of Chinatown, a rather faded symbol of Italian-ness. That’s why I went to Arthur Avenue in the Bronx to find what remains of the city’s community of Italian origins. The street was definitely in New York, I couldn’t be mistaken, but if I squinted my eyes to the point of blurring, and let myself be guided by the sounds and smells, I was carried back to the tree-lined streets of Parioli – the Roman neighborhood where both my grandmothers lived – with their corner groceries, wine and oil stores, that each spilled their goods onto the sidewalk.

Brave New World

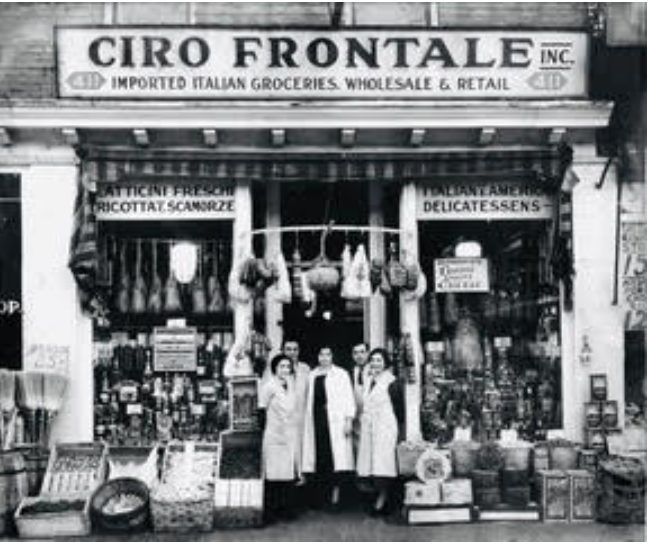

That was back in the Rome of the 1960s, and those ‘mom & pop’ shops – that seemed like dimly lit caves, with hundreds of cans climbing the walls, sausages and cheeses hanging from the ceilings – spread their pungent scents of pecorino, salt cod, anchovies in oil, cold cuts, and freshly baked bread. On Arthur Avenue there was even a coffee roaster whose fragrance dominated one side of the street and even more powerfully evoked my Roman childhood. But I was especially attracted by one particular grocery store, exactly like the ones I have seen in certain central districts of Naples – those whose matrons with dyed curls sitting imposingly at the checkout counter, are intent on carefully wrapping every object – from a bottle of wine, to a jar of peeled tomatoes – in tissue paper.

The store hadn’t changed much over the decades judging by the Art Deco tiles and wooden display cases full of cold cuts and cheeses – even caciotta, provola, and caciocavallo; the shelves loaded with packages of imported pasta, and the ceiling obscured by a thick rain of hams, loins, and salami of all shapes and sizes. I gazed in wonder at pyramids of tins of peeled tomatoes that ran around the shelf tops, with Mount Vesuvius coloring their labels. Sharpening my eyesight, I even spied, at the high point of one pyramidal altar, a photo portrait of Mussolini kept under cellophane, flanked by images of two patron saints. Dan, who was accompanying me, exposed me as a paesano to the grocer, he in a long white coat, who immediately began to speak in what he believed to be Italian – which, I supposed, was nothing more than the dialect his grandmother spoke at home, and which certainly did not correspond to what is spoken today in the region from which she’d emigrated.

We went to lunch at Mario’s where Capri’s Blue Grotto glistened, and Vesuvius loomed over the Bay of Naples, in a series of ninety-year-old oil paintings around the walls. From the simple pizzeria of its beginnings – when pizza was still a foreign specialty – the place had taken on a respectable air, with tables covered in starched white tablecloths placed in rows between the supporting columns of the dining room. Francis Ford Coppola had chosen Mario’s to shoot a scene from The Godfather, but when the patriarch, Mario himself, understood there would be a shootout in his restaurant, he forthrightly declined.

Neapolitan panoramas, Mario’s ristorante italiano

Regina, Mario’s niece, corrected me when I said the ambiance had something of an old-fashioned Italian feel to it. We do Neapolitan cuisine, she replied. I was relieved, interpreting this as a guarantee of quality, since ‘Italian cuisine’ is only an abstract concept, only authentic when regional cooking is present. From the menu, written in a touchingly vernacular Italian, we chose escarole in broth and an octopus salad; then braciole with peppers, stewed tripe, and – a Mario’s specialty – Roman-style skewers of bread and cheese, fried, and topped with anchovy sauce. When I commented on the views of Naples adorning the walls, Regina surveyed the amber patina that covered them and said, I’m sure Naples doesn’t look like that anymore. She was right: the idyllic gulf and harbor scenes preserved at Mario’s would now be filled with buildings, hotels, cranes, and cruise ships the size of citadels. But Regina couldn’t know because neither she nor her father, she confessed embarrassedly, had ever set foot in Naples, or anywhere else in Italy.

While staying in Morocco it was not easy to find the Casa d’Italia in a former pasha’s residence in the center of Tangier. We circled at least twice, following the vague instructions of a porter at the nearby Italian Hospital. In the portico of the restaurant, where a ficus plant proceeded torturously along the ceiling, reminiscent of Catholic religious institutions, a group of French people and other expats were having lunch. The menu was definitely Italian with entrees like spaghetti alle vongole and ossobuco alla milanese, but Dan and I ordered an excellent and plentiful fish fry accompanied by a dry white wine from Meknès. The maître d’ discreetly officiated from behind a column and directed an attentive yet unpretentious service. We returned from time to time gladly because it seemed to us to be a place where one returns with the illusion of, perhaps, being recognized and greeted politely as a regular customer.

A pasha’s palace, now Casa d’Italia, Tangiers

We had lunch there again on a radiant New Year’s Day morning. When we arrived, the portico was deserted and the tables set with crisp linen tablecloths and napkins, and thick white porcelain dishes, waiting for hoped-for patrons to park their cars in the shade of the palm trees surrounding the uneven courtyard. We basked in the colonial atmosphere while a host of idle waiters in starched white jackets scampered around like schoolchildren on a day off. A few customers eventually arrived in dribs and drabs – maybe expected, maybe not – the ladies in this group receiving hand-kissing from the maître d’. Everyone was welcomed with good wishes and hugs, and all were seated at a table on the far end of the colonnade. Then the sun began to beat down between the slats of the plastic ice-cream parlor-like curtains, discomforting them, and the waiters were asked to transfer crockery, personal belongings, cups of seafood cocktail, to the opposite side of the veranda. From behind an arch I saw the staff venting their discontent by aping, with eye-rolls, some of the diners.

New Year’s Day lunch on the colonnade