By David A. F. Sweet

One of seven children who grew up in the coal country of Western Pennsylvania, Bill Schmidt seemed destined to work in the mines. After all, his father Louis labored as a miner for decades. Attending college was far-fetched; Louis, suffering from black-lung disease and depression, committed suicide when Bill was 2, and there was no money to pay for tuition even if the teen with lackluster grades was accepted.

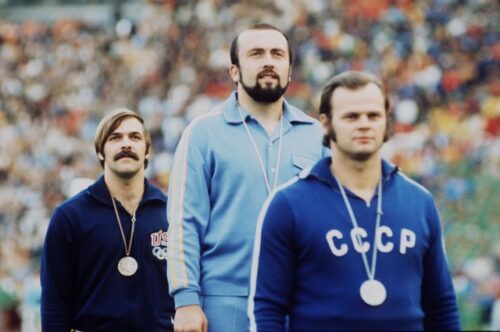

Bill Schmidt captured a bronze medal during the 1972 Olympics.

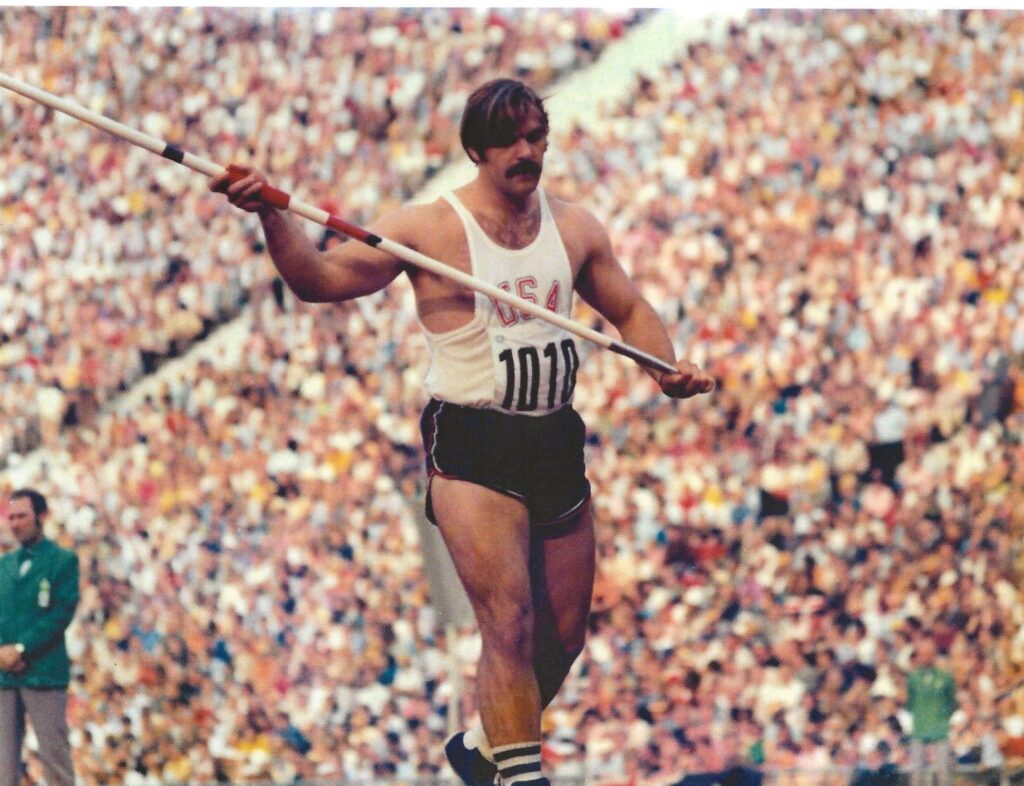

Yet he rode out of Southview, Pa. in a most unlikely way: throwing a spear, an ability that helped propel his life to startling heights.

The former Chicagoan story is told in his autobiography Southview to Gettysvue. Published last year by Newman Springs Publishing of New Jersey, it tracks how he captured a bronze medal in the javelin at the 1972 Summer Games in Munich – the ones marred by terrorism – to become the only male American to bring home a medal in that sport in the last 51 years (American Kate Schmidt, no relation, also earned a bronze medal in the javelin in 1972. The duo is the answer to a Trivial Pursuit question.).

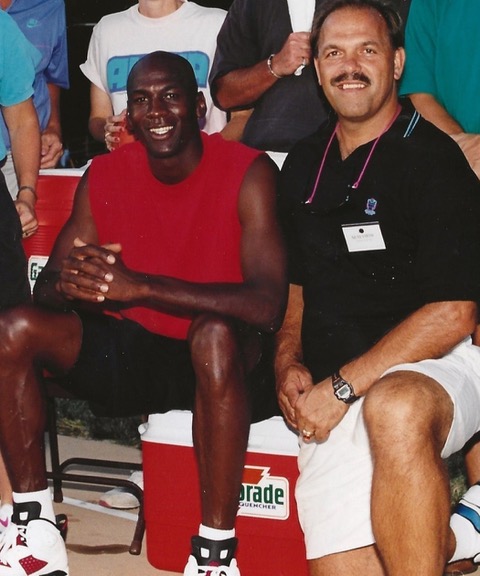

But that’s just part of the story. You may not have heard of Bill when he lived in Chicago, but you definitely know what he accomplished. During 15 years at Quaker Oats, he took a sleepy sports drink called Gatorade and – thanks to signing Michael Jordan to a 10-year-deal to promote it and negotiating multi-million-dollar contracts with the four major sports leagues, among other accomplishments – helped the brand grow to $1.75 billion in annual sales from $80 million.

And at the start in 1984, his marketing budget was zero.

“I had a blank canvas and no checkbook,” said the brand’s first vice president of sports marketing.

Back then, Gatorade was simply known as a thirst quencher. Athletes drank it, but sports’ promotion around the brand (which Quaker Oats had acquired from Stokely-Van Camp) was limited to relationships with the PGA Tour, NASCAR, and the NFL.

Schmidt had an insight to get the people at the grass roots – the trainers – to buy in. In 1985, he spent weeks in Florida and Arizona meeting team trainers at 5:30 a.m. before baseball spring-training games.

“I’d take coffee and donuts to them,” said Schmidt of his effort to not only sell them Gatorade but persuade them to place the coolers prominently in the dugouts. “I never even went to the games.”

Those who remember the end of important NFL games in the 1980s will also recall the birth of the Gatorade Dunk. Schmidt negotiated the deal that mandated that all NFL teams must have Gatorade on the sidelines. But he had no notion about the publicity those coolers would receive during a playoff game between the New York Giants and San Francisco 49ers in 1987.

After Schmidt signed Michael Jordan to a 10-year deal with Gatorade, the Be Like Mike commercials began and became a huge hit in the 1990s.

“It was totally serendipitous,” said Schmidt of the Gatorade Dunk on national TV, with New York Giants coach Bill Parcells getting doused after a big win. “(John) Madden gets the telestrator and starts diagramming what looks like a play, but it’s the Gatorade Dunk. I said I’ve died and gone to heaven.”

“The next day at work people said we need to capitalize on that. I said, ‘No let’s let it play out.’ There was pushback. I said, “OK, we have to at least do something with Bill Parcells. Let’s reinforce his wardrobe.” Schmidt sent the famous coach a gift certificate for Brooks Brothers clothes to replace his Gatorade-drenched outfit.

Then came Michael Jordan. Just like Nike wooed him at the dawn of his career against other shoe companies (as recounted in the movie Air, which is marred by many Hollywood liberties), Schmidt tried to lure him away from behemoth Coca-Cola in 1991.

Quaker Oats CEO William Smithburg signed off on paying Jordan at least $1 million a year for a decade, a far bigger deal than Coke was giving him. Schmidt promised to put him at the center of advertising; Coke had barely used him in commercials. Still, there was no guarantee Jordan would switch.

“I was nervous throughout the whole deal,” Schmidt recalled.

Gatorade landed Jordan. Months later, he won his first of six NBA titles. The next year, he and the Dream Team won the gold medal in Barcelona.

Return on investment can be hard to measure in sports marketing, but in at least one area, Jordan’s impact on Gatorade was clear.

“Michael helped drive us into 24 countries we hadn’t been in before that didn’t even know what a sports beverage was – but they knew who Michael Jordan was,” Schmidt said.

Of course, the Be Like Mike commercials (“I don’t think he’s been called Mike since,” Schmidt noted) were a massive hit – in fact, they were recently resurrected by Gatorade, now owned by PepsiCo.

“It was a simple message – if you could be like Michael Jordan for one day, would you do it? Absolutely,” said Schmidt, who was involved with the creation of the commercials and responsible for bringing shaving cream and a razor so Jordan at times could remove his summer goatee before filming.

By the turn of the century, Gatorade was immersed in sports – and profits. As former NBA Commissioner David Stern told Terry Lefton of Sports Business Journal about Schmidt’s impact, “People forget that sports drinks were hardly a category – he defined it.”

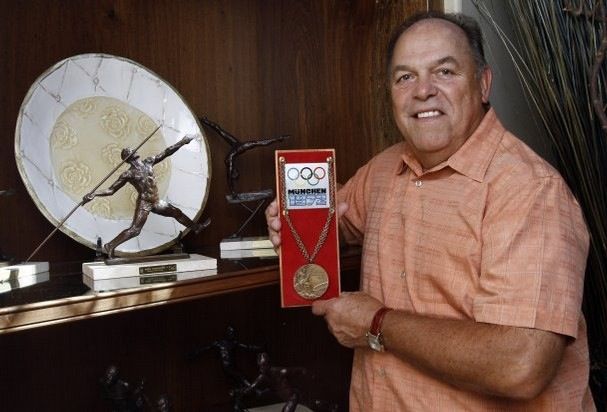

Schmidt displays his bronze medal.

At the same time, let’s not overlook the importance of the javelin to Schmidt’s story. Thanks to a search conducted by his high school track coach, Schmidt threw as a walk-on athlete at North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), where he eventually earned a scholarship. (The team’s shot putter? Future NFL Hall of Famer Mean Joe Greene, whose Coke commercial is arguably as iconic as Be Like Mike.) Despite setting the javelin record at the World Military Championships in Finland in 1971 when he served with the U.S. Army, Schmidt was a long shot to make the Olympic team. He was ranked ninth in the United States, and he never had a javelin coach; Schmidt taught himself by watching loop films of world-class javelin throwers.

Yet he won the Olympic Trials to earn a spot. The morning of qualifying in Munich, he walked to the basement of his Olympic Village dorm expecting transportation. There was none. Panicked, he ran the three miles to the stadium – but the guards’ said he was too late. Schmidt knocked the guards to the ground and made it to the qualifying round without any warmup. He qualified that day and, in the Finals, the next day, his throw of 276 feet 11 1/2 inches earned him a bronze medal at the 1972 Games.

What did he like best about competing in the javelin throw?

“Your success was dependent on you and you alone,” said Schmidt. “There was also no interpretation of technique. You threw the farthest, you won.”

There is much more. On the sports-marketing side, he promoted sports at the World Fair in Knoxville, Tenn., in 1982 – the first World Fair to feature sports – with no budget. He was responsible for the success of eight sports during the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. On the personal side, a brother was abused by priests (which led to about 60 years the brother spent in psychiatric facilities and mental hospitals). Schmidt says the Catholic Church failed his family. At the same time, he writes, “I believe Jesus Christ never failed me in my life. I give him all the praise and glory for all that I have accomplished.”

Schmidt was a powerful presence throwing the javelin at the 1972 Olympics.

Though the title Southview to Gettysvue may not resonate with many readers (the subtitle From a Coal Camp to Olympic Podium, to Courtside with Michael Jordan is definitely an attention-grabber), Schmidt has written a powerful book of interest to anyone who yearns for an insider look at Michael Jordan, the memories of an Olympic medalist or a rags-to-riches story.

“It doesn’t matter where you were born,” he said. “That doesn’t determine where you’ll end up.” Schmidt is certainly proof of that.

The Sporting Life Columnist David A. F. Sweet wrote a book about the 1972 Olympics called Three Seconds in Munich. He can be reached at dafsweet@aol.com. Southview to Gettysvue is available at amazon.com