By Judy Carmack Bross

The Kalo Shop 14K necklace with pearls and garnets. Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers

The just opened Driehaus Museum’s stunning “Chicago Collects: Jewelry in Perspective,” motivated us to learn more out City’s jewelry legacy from local historian and expert Darcy Evon, author of Hand Wrought Arts & Crafts Metalwork & Jewelry 1890-1940, a comprehensive and beautiful book which features Midwest pioneers who influenced artisans across the country with their exquisite original jewelry.

Darcy Evon

Cover of Darcy Evon’s book

The Chicago Arts and Crafts Movement was ignited at the World’s Fair of 1893. Two years earlier, the Art Institute, under the leadership of the Founder and Dean of the Chicago School of Architecture Louis Millet, offered a three-year course in decorative design that drew hundreds of students from all over the country–predominantly women, who aspired to careers in the arts. The program touted that, “Graduates usually find employment at once.”

Art and Handicraft at the Women’s Building. Book cover from the 1893 World’s Fair.

Louis Millet, first Dean of the Chicago School of Architecture who taught the three-year Decorative Design degree program at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1891 to 1918. Hundreds of women and some men graduated from the program and pursued good paying jobs in the arts. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

Art Institute of Chicago copper and sterling pin made by C.D. Peacock. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

By 1895, artisans began to focus on handmade metalwork and jewelry that became characteristic of the city’s arts and crafts style. Early pioneers included Christia Reade–who worked as a designer for Louis Millet, and Jessie Preston, who made unique candelabra and hand wrought jewelry. Classes were taught at workshops, studios and institutes throughout the city–including Hull-House that catered to the many immigrants who had settled nearby. The Tree Studios became one of the country’s earliest art colonies and soon the Marshall Field & Co. Annex and the Fine Arts building served as modern arts and crafts incubators. Guided by the philosophy of the British Arts and Crafts Movement, handmade jewelry and metalwork became a commercial movement in Chicago, providing exceptional careers–especially for women and immigrants. Everyone knew everyone, the women served together on boards and art juries and were definitely acquainted with arts and crafts architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan. “These pioneering artists laid the foundation for a revolution in art and design,” Evon told us.

Kalo Arts Crafts Community House in Park Ridge, IL (1907-1914). Men and women silversmiths, designers, and crafts workers who were a part of the Kalo Shop. Courtesy of Darcy Evon

“In 1900, Clara Barck Welles and five other graduates of Millet’s decorative design course established the Kalo Shop as an avant-garde design studio. With its name taken from the Greek word to make things beautiful, the Kalo Shop became synonymous with innovation and entrepreneurship in the arts and crafts design of metalwork and jewelry. With the creation of what is ‘beautiful, useful and enduring’ as its mission, the Kalo Shop became a leader of emerging art industries sweeping America. It was the largest, longest lasting and most successful of the plethora of shops and workshops that developed after the 1893 World’s Fair,” said Evon, who is the historian for the Kalo Foundation in Park Ridge, once a major arts and crafts hub.

Portrait of Clara Barck Welles, 1906. Courtesy of Stanley Hess.

The Kalo retail shop at 222 N. Michigan Ave, where it was located from 1936 to 1970. Courtesy of Sharon Darling.

Early logo of the Kalo Shop, 1900. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

Hand Wrought mark on Kalo jewelry that was used from the 1930s to 1970. Earlier jewelry pieces were stamped Kalo. Courtesy of Darcy Evon

Early Kalo necklace in sterling silver and pearl. Courtesy of Millea Bros. and John Walcher. |

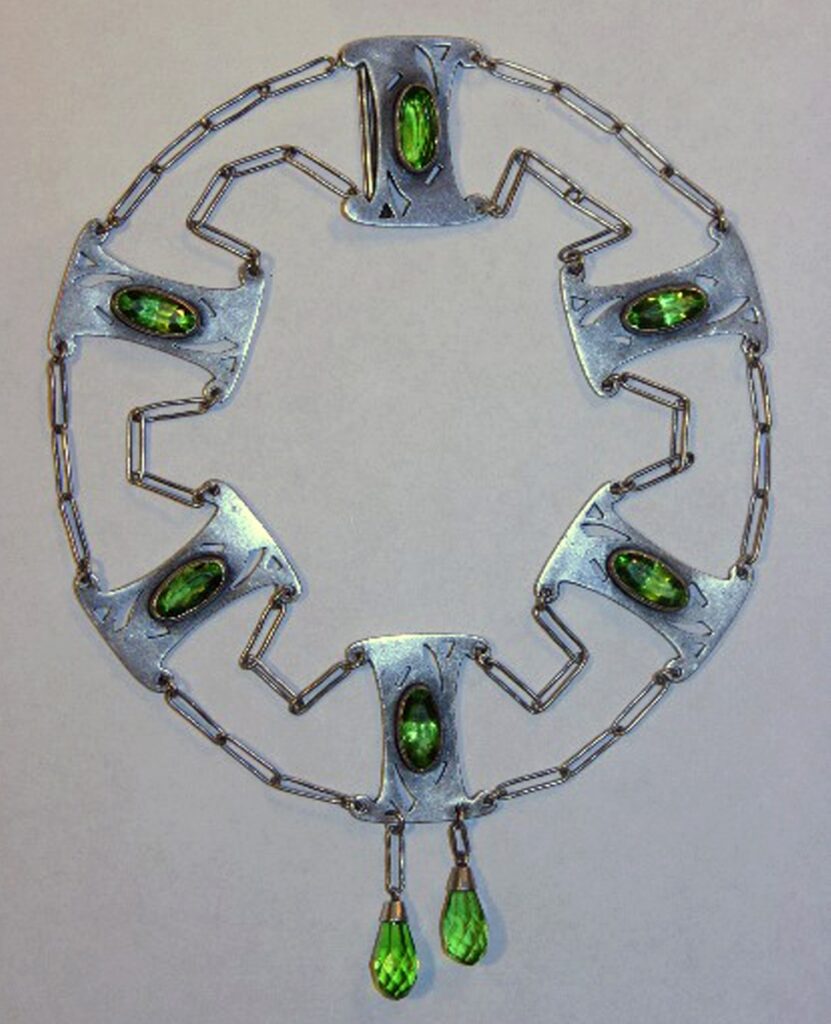

Kalo sterling silver necklace with peridot. Courtesy of Boice Lydell |

Unusual Kalo necklace in sterling silver adorned with pearls. Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers |

Geometric Kalo brooch in 14K and opal. Courtesy of Didier LTD. |

Amethyst ring in 14K by the Kalo Shop. Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers. |

Kalo tourmaline, moonstone, and silver gilt necklace, Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers

|

Kalo enamel and sterling silver necklace, bracelet, earrings and brooch. These innovative designs were made by Kalo silversmith Yngve Olsson at the Kalo Shop. Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers. |

Floral motif sterling silver necklace with peridot and pearls at the Kalo Shop. Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers |

Collection of Kalo hand wrought sterling repousse brooches in a variety of nature motifs. These extremely popular designs were made from c.1926 to 1970. Courtesy of John Walcher, Darcy Evon, and Chicagosilver.com.

“Clara Barck Welles was a very influential leader who launched the Kalo Arts Crafts Community in Park Ridge, IL that included workshops and a school where aspiring women artisans learned how to design and make hand wrought metal and jewelry. Initially taught by Matthias Hanck, many of the items produced by graduates were sold at the Kalo Shop in Chicago. Welles’s relentless focus on quality and innovative design was coupled with unparalleled output. Kalo Shop jewelry was made by some of the most talented jewelers and silversmiths in the country, interns, apprentices, and graduates of the Kalo School.”

Copper candlesticks made by Grant Wood for the Volund Crafts Shop that was in Park Ridge, IL from 1914 to 1915. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

Copper candlesticks made by Grant Wood for the Volund Crafts Shop that was in Park Ridge, IL from 1914 to 1915. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

Sterling silver bar pin with flower motif made for the Volund Crafts Shop. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

“Welles took an especial interest in Grant Wood after they met at the Art Institute where he exhibited copper work at the annual arts & crafts show. He became an apprentice at the Kalo workshops and later co-founded the Volund Crafts Shop in Park Ridge. After World War I started, the shop failed and Wood returned to Iowa broke and miserable. In 1930, he returned to Chicago as a painter and won the Art Institute’s purchase prize for American Gothic. Grant Wood became a world-wide sensation almost overnight.”

“Clara championed collaboration not competition, and encouraged workers to start their own companies,” Evon said. Kalo alumni opened studios and important jewelry and design companies, taught manual arts and influenced a generation of industrial designers through the Arts and Crafts Movement into the Modernism era. The result was innovative and distinctive hand wrought jewelry and silverwork with 70-years of works,”

Evon told us about two other leading women jewelers whom she most admires, and about the Marshall Field & Co. Craft Shop.

“Jessie Preston, who became one of the first women to design in metalwork here, creating unique candlesticks in 1895. She was also one of the earliest women craft workers to take a studio in the Fine Arts Building and she helped define the progressive nature of the artist colony for the next 20 years. During World War I Preston helped craft metal work for military and rehabilitation purposes.”

Blister pearl and sterling silver brooch made by Jessie Preston. Courtesy of Boice Lydell.

Collection of jewelry made by Jessie Preston published in The Sketch Book, Dec. 1906.

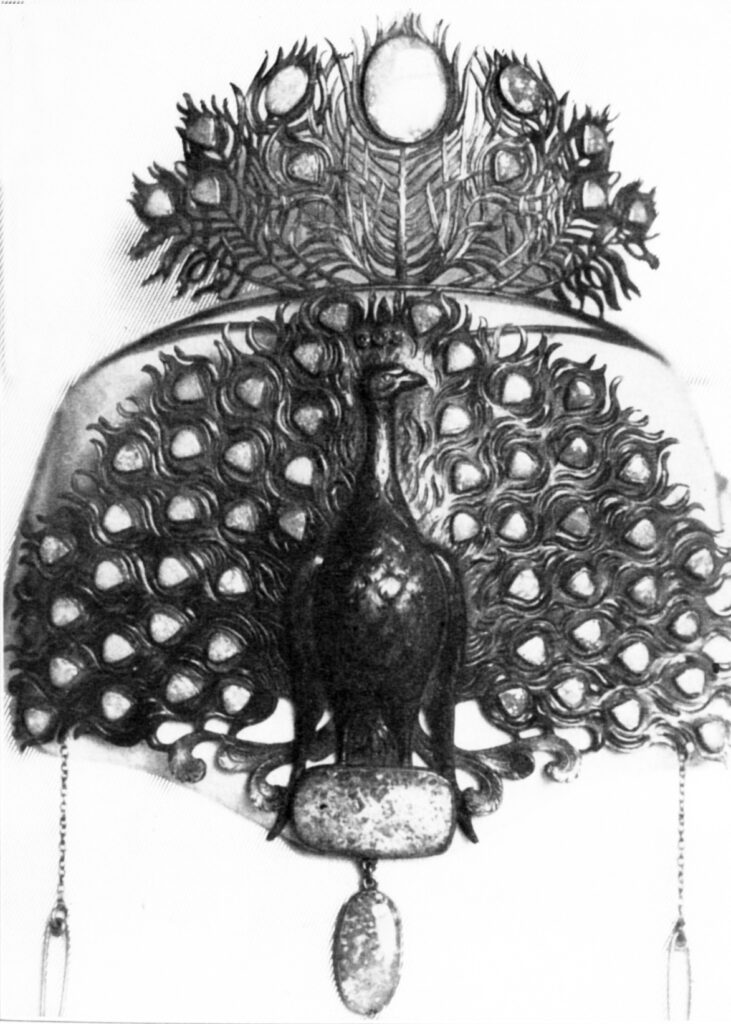

Leonide C. Lavaron, whose hand-painted china appeared in the World’s Fair of 1893, found that art metalwork and jewelry was more lucrative than painting and established her own studio in the Marshall Field & Co. Annex in 1901, moving to the Fine Arts Building in 1907. In 1905 she exhibited her famous peacock tiara made in gold set with diamonds, and the iridescent hues of her burnished copper pieces were said to pattern ancient Egyptian creations. Lavaron had several highly skilled jewelers who worked for her, including Emil Kronquist. She exhibited from Boston to Pasadena and her work was also featured in many of the Art Institute shows and in the leading art journals of the time. She remained active until her death in 1931.

Leonide C. Lavaron was a painter who exhibited painted china at the World’s Fair of 1893. She later became famous for her iridescent copper, shell lamps, candlesticks, and a broad range of jewelry.

Lavaron’s studio in the Fine Arts Building, 1911. Notice the broad range of artistic wares.

Studio postcard of Lavaron’s studio. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

Lavaron’s famous peacock tiara in gold with opals, c.1906.

Copper belt buckle with chrysoprase and red gemstones by Lavaron. Signed L.C.L. Courtesy of Darcy Evon

“Soon after the turn of the century, Marshall Field & Co. established itself as a major manufacturer of wholesale and retail arts and crafts jewelry, silver and metalwork. They were known for introducing the latest designs as well as beautiful custom work,” Evon said. “Its innovative workshops provided training for dozens of workers who went on to start their own companies or work for leading artisans of the period. They produced wholesale jewelry and silver in c.1903, and launched an important Craft Shop featuring innovative metalwork and jewelry for retail customers from 1907-1917.

Carved and chased 18K gold brooch with pears, made by Lavaron worker Emil Kronquist for his fiancee, 1906. Photo by Darcy Evon.

Marshall Field Craft Shop Workers (Photos courtesy of Darcy Evon)

A sterling silver acid-etched brooch made in the Craft Shop. These and similar items became extremely popular throughout the Midwest, c.1907-1911.

Chicago was a major jewelry-making center with hundreds of jewelry makers for many years. People would travel to Europe, Asia and South America to obtain stones. Ervin Lewy, one of a family of local jewelry makers, died on the Titanic on his way back to Chicago with a collection of purchased gems and hand carved cameos.

We asked Evon what were the most popular stones in arts and crafts settings.

Hallmark on the brooch.

“Between 1911 and 1919 cameos were in vogue again and many artists would go to Italy to find them. Prominent gems were lapis lazuli, turquoise, opal, chrysoprase, carnelian, onyx and moonstones. Pearls were also popular, including river pearls which you could collect yourself. Buyers would return from a trip with loose stones and ask the artist or jeweler to design them something special.”

Many Chicago jewelers excelled in metalwork and jewelry by hiring their own workers or by contracting with individual artisans on special order work. Important firms included the Jarvie Shop, Art Silver Shop, C.D. Peacock, Eicher-Andersen Studio, Hanck’s Art Jewelry Shop, Hull-House Shops, Lebolt & Co, Petterson Studios, the Randahl Shop, the Cellini Shop, J. Milhening, the Volund Shop (separate from the Volund Crafts Shop founded by Grant Wood and Kristoffer Haga), the Tre-O Shop, and many others. Petterson, Randahl and Lebolt made a broad range of hand-made silver items for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933-1934, and Green Duck Co., a local novelty manufacturing company, made the Fair’s souvenir spoon.

Chicago Arts & Crafts 14K and sterling coral cameos by Lewy Bros., The Julmat, Brandt Metal Crafters, J. Milhening, Lebolt & Co, John P. Petterson, and the Kalo Shop. Courtesy of Darcy Evon.

Sterling silver brooch with agate from The Jarvie Shop. Courtesy of Rago Auctions and Boice Lydell.

Lebolt & Co. 14K pendant.

Sterling silver necklace with pearls by Matthias Hanck. Courtesy of Toomey & Co Auctioneers.

Evon, an historian, arts and crafts scholar and entrepreneur who has several pieces in the current Driehaus show, grew up with a passion for the past, touring garage and estate sales with her mother when she was a child. “At a jewelry show in Ann Arbor in 1989 I bought seven beautiful arts and crafts pieces. I decided I had to read up on them and discovered Sharon Darling’s landmark book Chicago Metalsmiths which she had written in connection with the show she curated at the Chicago History Museum. It was the first of its kind, as most early metal crafters were totally unknown.

“In 1993 I began my research in Chicago and spent lots of time in the reading rooms of the Chicago History Museum, the Newberry Library and the Art Institute as well as visiting lots of local historical societies to learn more about artists not included in Metalsmiths. I did extensive genealogical research as well, tracking down and interviewing descendants of these artisans. I wrote articles published in the Chicago Sun-Times and suburban newspapers that prompted families to contact me as well. It is very hard when you ask people about two generations back, and you always have to confirm information with historical documents.”

Where to buy Chicago Arts and Crafts jewelry?

“Hand wrought jewelry and metalwork takes an incredibly long time to make, and not that many people these days have the patience or training to do it, “ Evon said. “Luckily, you can still find beautiful Chicago arts and crafts jewelry on eBay, Etsy and on auction sites. You can check out liveauctioneers.com for current sales.

We will be telling you more about the Driehaus exhibition soon.