By William Tyre

DINING ROOM (Photo by James Caulfield)

On a brisk autumn day in early December 2023, a truck pulled up in front of the landmark Glessner House at 1800 S. Prairie Avenue. Soon a massive oak sideboard emerged, weighing more than 400 pounds, as well as all the pieces needed to assemble a 16-foot extension dining table. The same scene would have played out in late November 1887, in anticipation of the Glessners moving into their new home the next week. The Glessners would not have been able to tell the difference between the original and recreated furniture pieces, as every detail was meticulously replicated, from the elaborate carved panels down to the iron brackets and screws no one could even see. This is the story of the new furniture.

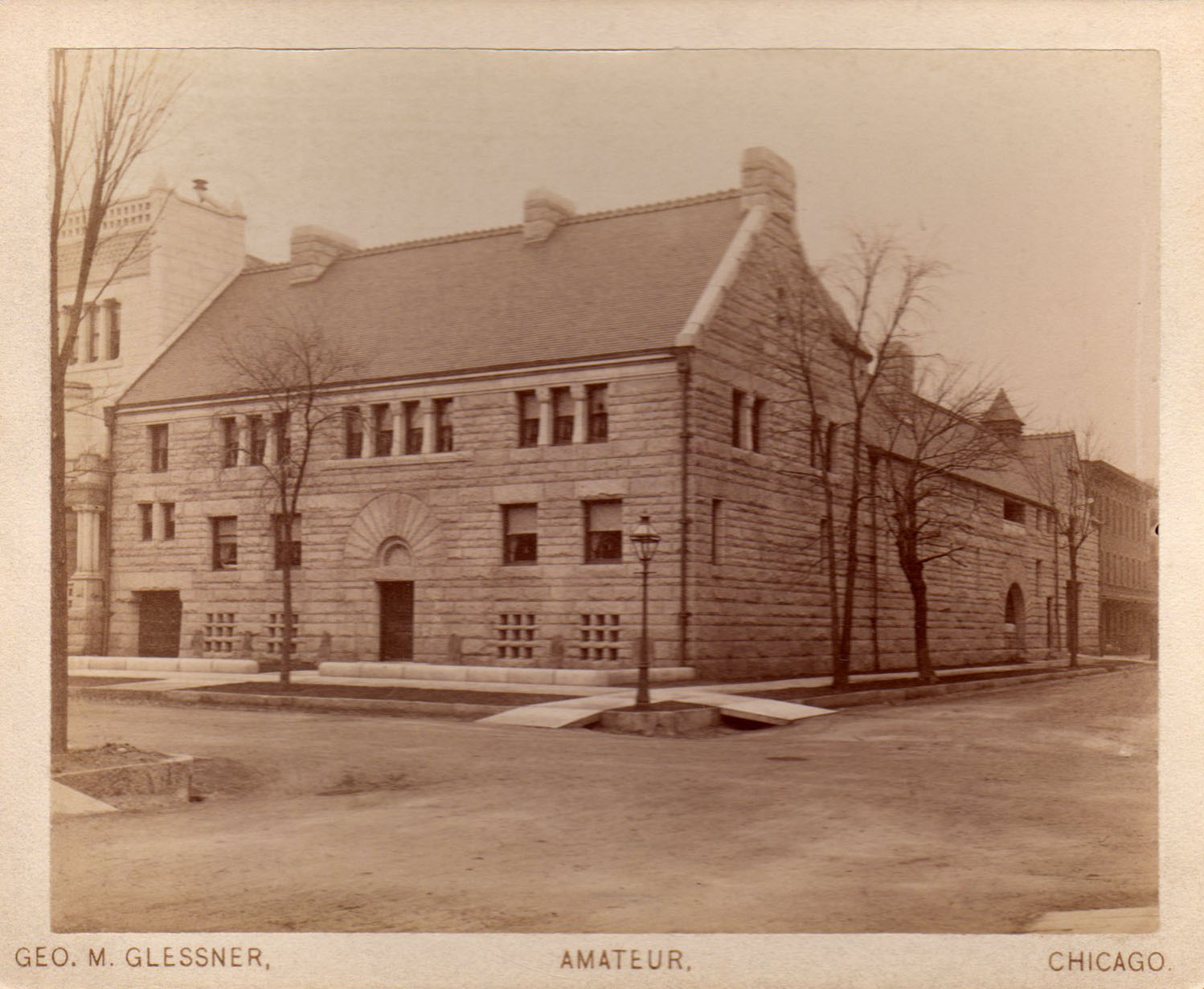

The story begins in the spring of 1885 when John and Frances Glessner selected Henry Hobson Richardson – the most celebrated architect in America at the time – to design their new home on Chicago’s exclusive Prairie Avenue, home to Marshall Field, George Pullman, and most of Chicago’s millionaires. Richardson’s innovative design, which positioned the main rooms into a south-facing courtyard, was not appreciated by most of the neighbors who referred to it as the fortress or the jail. Pullman, whose home was catty-cornered to the Glessners, was quoted as saying, “I don’t know what I ever did in my life to deserve having to look at that every day when I step foot outside my front door.”

EXTERIOR

Although the exterior of the house, clad in rusticated Braggville granite, represented Richardson’s mature style (which became known as Richardsonian Romanesque) and did give the appearance of a fortress, the interior was warm and inviting. Richardson designed the rooms to accommodate Frances Glessner’s request that the new 17,000 square foot house preserve the “cozy feeling” of the smaller home they were living in at that time at Washington and Morgan streets (demolished 1888).

Richardson died in April 1886, just after finishing the design of the new house. It was completed under the supervision of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, the successor firm which later gave Chicago both its Art Institute and Public Library (now the Cultural Center). The 28-year-old Charles Coolidge, one of the partners in the new firm who became a close friend of the Glessners, designed the furniture for the oak paneled dining room which measured 18 by 27 feet, making it the largest room in the house. Quartersawn white oak, used for the mouldings, fireplaces, and staircases throughout the house, was selected for the sideboard, dining table, and eighteen chairs. The elegant carvings captured the details from the historic Romanesque buildings upon which Richardson based his designs.

DINING ROOM CIRCA 1888

The furniture witnessed decades of the Glessners’ elaborate eight-course dinners that frequently included artists, architects, musicians, authors, and university presidents as guests. As founders and major supporters of what is now the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, they welcomed the leading musicians of the day including Ignacy Paderewski, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Enrico Caruso, to name but a few. Theodore Thomas and Frederick Stock, the first two music directors, were regular guests and often celebrated Thanksgiving and Christmas with the family.

The furniture was made by A. H. Davenport and Company, a prominent interior decoration and furniture making firm based in Boston. Their chief designer, Francis Bacon, had previously worked as an architect in Richardson’s office, so it is no surprise Richardson frequently employed the firm to execute his designs. Bacon is credited with the design of the Glessners’ Steinway grand piano, with its elaborate inlay work of various woods and mother of pearl set into the mahogany case. Davenport created numerous other pieces for the house ranging from the massive partners desk in the library to bedroom suites, and an assortment of tables, chairs, and cabinets.

Davenport had an outstanding reputation. One of their largest commissions consisted of 225 pieces of furniture and decorative items for the Iolani Palace, the royal residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawaii, completed in 1882. Much of the original furniture is still in place in the house, now open as a house museum. In the early 1900s, architect Stanford White engaged Davenport to make the furniture for the state dining room in the White House during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Many of those pieces are still in use.

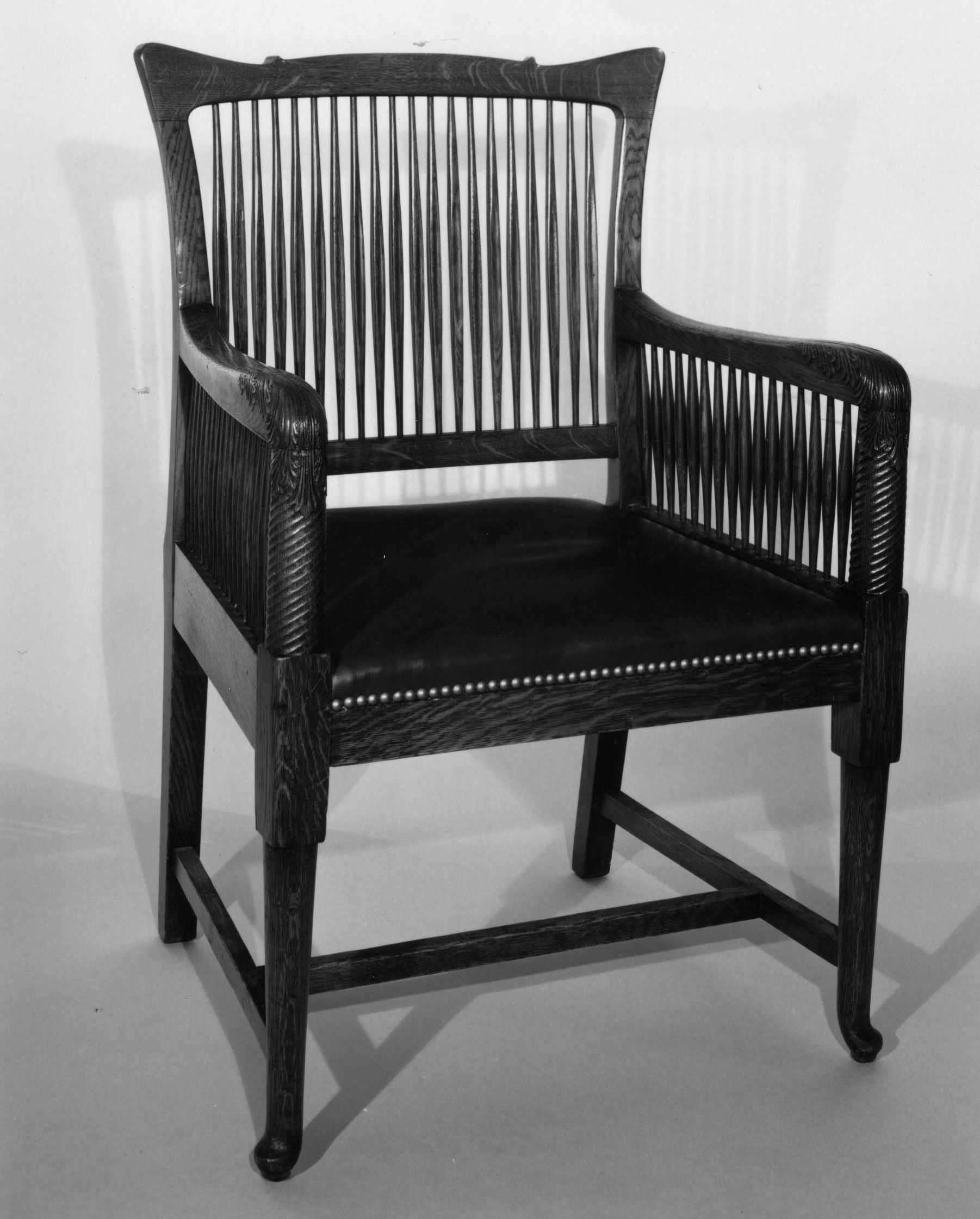

The Glessners’ dining table measured six feet in diameter when closed. It was supported by four slightly tapered square legs, each decorated with acanthus leaves and paw feet. Ten one-foot leaves expanded the table to sixteen feet, providing seating for eighteen. The chairs, similar in design to other pieces designed by Richardson, were an interesting mix of Colonial Revival, specifically the slender spindles reminiscent of Windsor chairs, and the Art Nouveau, including the sinuous curves of the top rail. The two armchairs featured shallow carved acanthus leaves on the armrests which gracefully curved directly into the spiraled arm supports.

ARMCHAIR

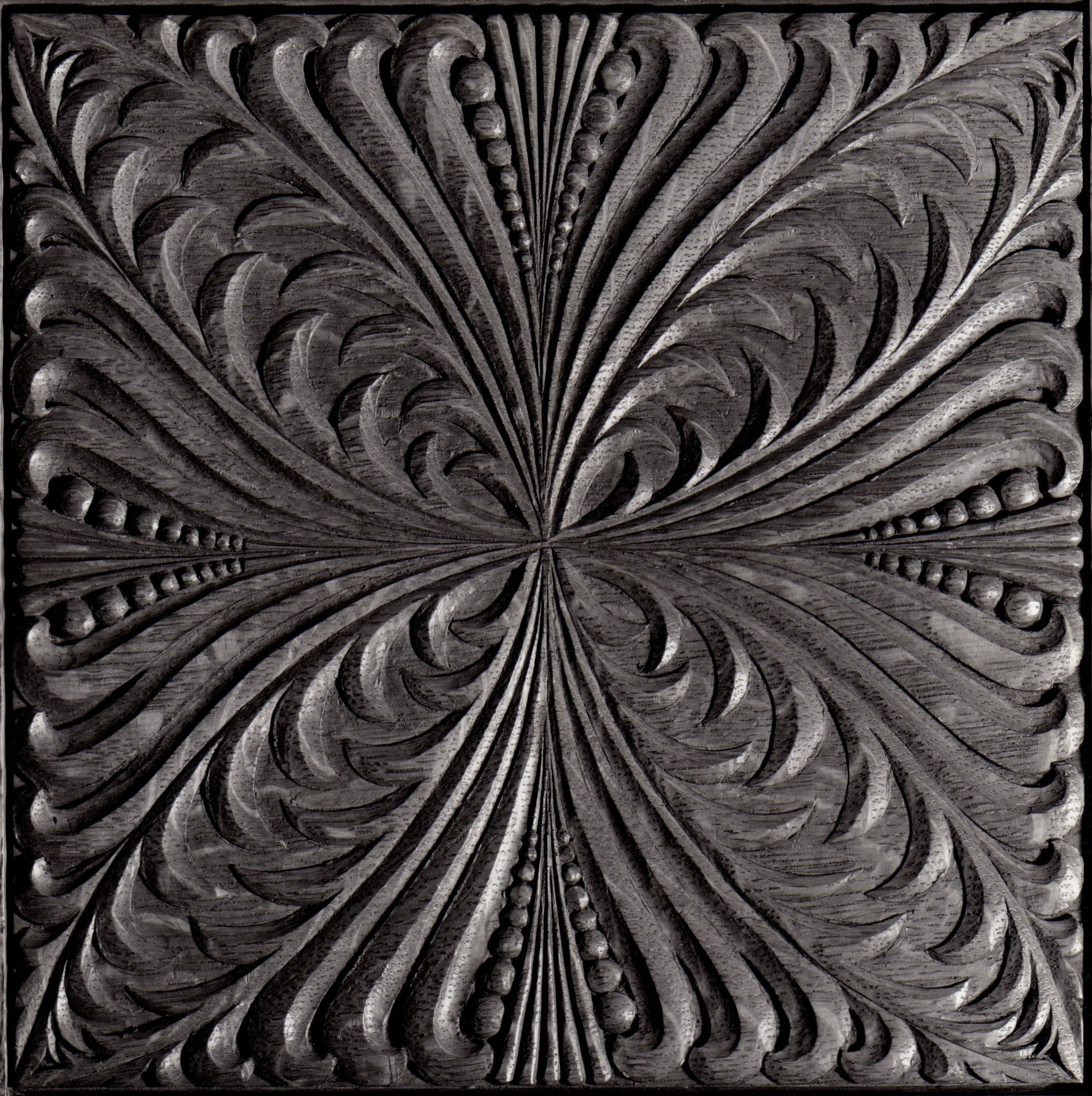

The sideboard was a tour-de-force of carved design. Although it is a free standing piece of furniture, the proportions align perfectly with the grid of oak paneling behind. An upper shelf, supported on four exquisitely carved columns, was designed to hold some of the Glessner favorite decorative objects. The ample top provided space for serving trays, decanters, and other items used during meal service. Five carved panels, each with a unique design, adorn the back of the piece and the two cabinet doors.

The Glessners paid a total of $10,000 for all the furniture in the house made by Davenport. When John Glessner died in January 1936, the dining room furniture was appraised for just $101, a sign of changing tastes and the country being in the midst of the Great Depression. The descendants removed most of the contents of the house, but as no one had a need for such massive dining room furniture, it was left in the building when it was donated to the Armour Institute (now Illinois Tech) in 1938.

The furniture remained when Armour leased and eventually sold the house to the Lithographic Technical Foundation, which moved the furniture to the second floor hall, using the table for meetings and conferences. When the Foundation moved to Pittsburgh in 1965, they sold the table, sideboard, and fourteen side chairs for $250, as their plans called for the house to be demolished. (The two armchairs and two remaining side chairs were left behind in the attic and were found when the house was saved from demolition and purchased in 1966).

For decades, a smaller table and sideboard were placed in the dining room along with the four surviving chairs, but they did not begin to portray the elegance that the room once possessed. In 2021, long-time docent Allan Vagner and his wife Angie, made a generous and visionary lead gift to recreate the table and sideboard. After an extensive search, Patrick Burke of Atelier Burke in Newton, Wisconsin was commissioned to recreate the furniture. Burke had trained as a woodcarver in northern Italy and possessed all the necessary skills to recreate Coolidge’s designs and Davenport’s expert craftsmanship.

DINING ROOM 1923

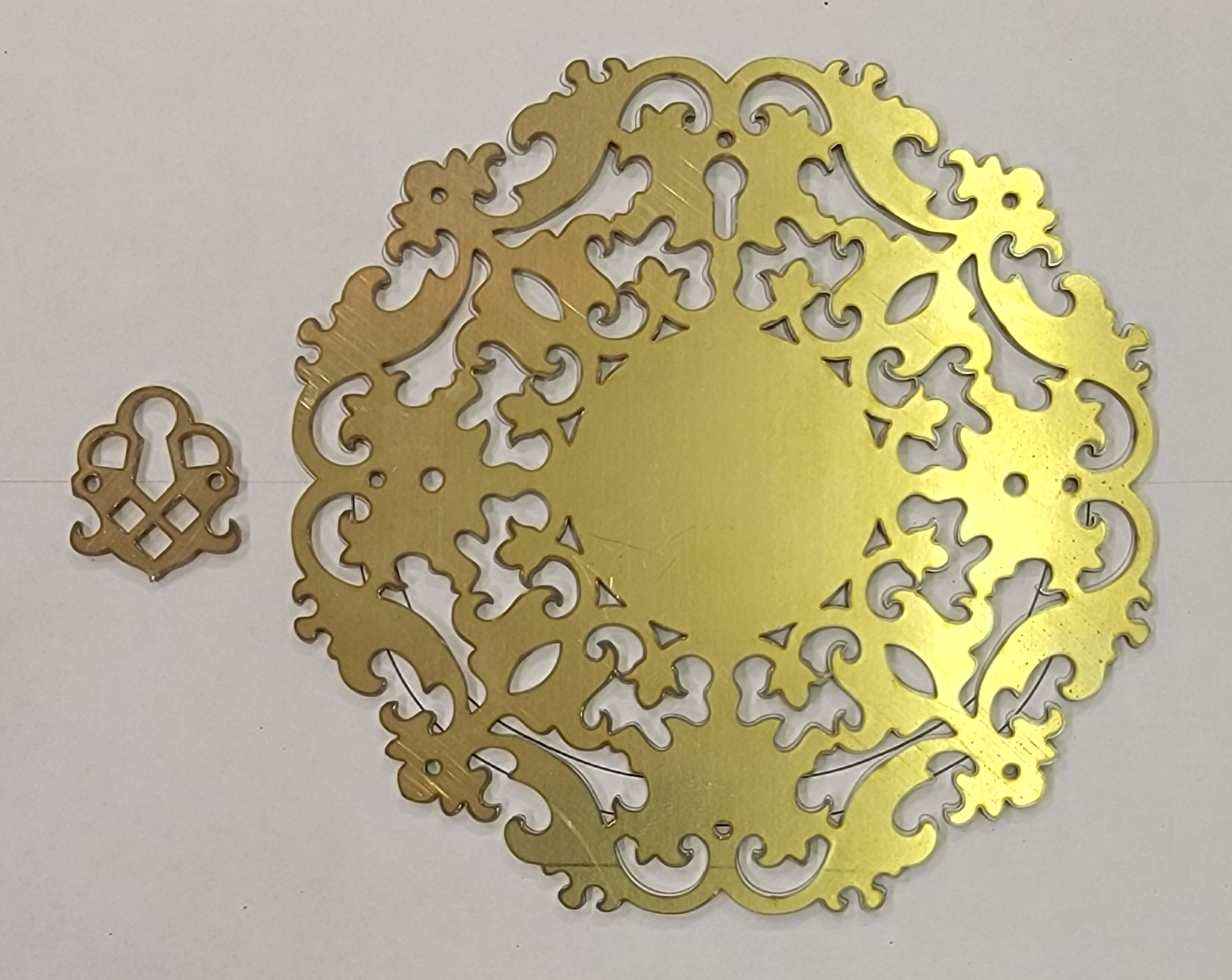

Historic images were analyzed for details. Two photographs, taken in 1923 by the firm of Kaufmann and Fabry, survived as 8×10 glass negatives, allowing the most minute details to be examined, including the distinctive brass drawer pulls and keyhole escutcheons. Since the furniture was being left in the house, the Glessners’ daughter, Frances Glessner Lee, also had the five carved panels of the sideboard professionally photographed in 1936.

CARVED PANEL

The size of the sideboard was easy to determine, using the oak wall paneling as a guide, as well as the set of original linen runners visible in the 1923 photos, which were still in the museum collection. The table size was a bit of a challenge. The room was measured, including the south-facing bay window incorporated into the room to accommodate the table at full length. Chairs were measured and etiquette books were consulted to confirm how much table space each guest should have (24 inches or more). It was ultimately determined the table was sixteen feet in length.

SCHWEBEL TABLE LEG

The Schwebel family owned a Davenport dining room table with nearly identical legs and allowed Patrick to come to Peoria to study it for details. David Martland, a major collector of Davenport furniture, invited Patrick to visit his homes in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Through these visits, Patrick gained a keen insight into exactly how the Davenport carvers executed their designs, and how they built the pieces, including the special hinges for the doors and the mortise and tenon joinery for the drawers.

Davenport pieces in the Glessner House collection were also examined, including the partners desk, which was found to have the identical keyhole escutcheons on the drawers, and the main hall fireplace surround, which had a similar egg-and-dart trim to the sideboard. Two headboards, made for the Glessners’ granddaughters and now displayed in the corner guest room, feature one of the five carved designs from the sideboard, albeit on a larger scale. Molds were made of several of the Glessner pieces for further study.

PATRICK MAKING MOLD

Production began with carefully selecting the quartersawn oak. The term refers to a specific way of cutting the oak logs to maximize the beauty of the grain, which also produces distinctive medullary rays across the grain, a unique feature of oak cut in this manner. Scaled drawings were produced and full size mockups were set up in the dining room to compare the dimensions and proportions with the historic photographs.

Two colleagues of Patrick selected and cut the wood, and assembled the furniture, while Patrick concentrated on all the elaborate carvings. A virtually endless variety of chisels were used for all of the fine detailing, each designed for a specific technique. The dining room table legs were initially modeled in clay until the exact profiles of the acanthus leaves and paw feet were perfected.

CARVING CENTER PANEL

The hardware, both decorative and structural, provided some of the most significant challenges. Some pieces, such as the bails (handles) and posts for the drawer pulls were cast using the lost wax method, but that was prohibitively expensive for other pieces like the elaborate filigree backplates. Those were hand cut after brass was obtained replicating the exact color of the late 19th century originals. Distinctive cast iron brackets unique to Davenport, used to hold the tabletop to the apron, were cast in a foundry. Joan Parcher, a prominent Providence, Rhode Island based jewelry designer and expert on historic furniture hardware, was engaged in this phase of the project.

BRASS HARDWARE

With all the pieces complete, the table and sideboard were carefully wrapped and packed for the trip from Newton to Chicago. Eight individuals were needed to get the sideboard into the house, using a specially built platform to hold the piece as it was carried up the front flight of stairs.

MOVING SIDEBOARD

The sideboard was reset with many of the pieces visible in the 1923 photos. The new furniture, and the identity of the lead donors, was revealed to an appreciative crowd on the evening of December 5, 2023. A second event took place on February 6.

SIDEBOARD

The final phase of the project will include replicating the missing side chairs. Patrick is hard at work on those chairs, and they are due for delivery in late September 2024. Once in place, the dining room will be offered as a unique venue for hosting dinner parties for up to eighteen people, just as the Glessners did a century ago.

For additional information and images, Glessner House has produced two “Secrets of Glessner House” videos available on YouTube:

Secrets Part 44 – History and Design

Secrets Part 45 – Recreating the Furniture

TABLE

For information on renting the dining room for your special event, call 312-326-1480 or send an email to info@glessnerhouse.org.