By Francesco Bianchini

If reborn in any other form, I’d be a caper bud, spending my brief existence basking in sunshine on an ancient stone wall, drunk from my own salty scent, tickled by sulfur-colored butterflies, bees, and lizards. Then I’d blossom into an elegant afternoon dress of white ruffles streaked with bold purple – nothing garish or pretentious – to make my entrance into society accompanied by the clatter of cicadas and bumblebees. I might also come to an untimely end but – all things considered – noble and productive. If someone were to take the trouble to harvest me before I bloomed, I would find myself in a glass jar, pickled in salt, vinegar, or oil – whichever you like – placed in the cool shade of a pantry, waiting to flavor any dish thanks to my exquisite versatility.

(from Pinterest) Capparis spinosa

No one wanted the caper badly, no one planted it or hoed it carefully; it came to flourish by virtue of its resilience, its ability to hunker down and thrive, perched in the interstices of arid limestone. It had no claims to water or other nutrients, just needing to be kissed from morning to night by the Mediterranean sun. But those who have tasted it chopped and mixed in a piquant sauce will not forget its taste, and will not forego that taste for anything in the world. I use capers in stuffed or sauteed escarole (with pine nuts, black olives, and a little garlic); in stir-fries with whatever vegetables I happen to have; in cacciatore sauce, and in pasta (whole-wheat spaghetti, olive oil, and fresh seasonal tomatoes). I never neglect to add capers to liver paté to give it that unique pungent touch. It’s worth mentioning that capers are rich in quercetin, a natural antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory, and they are studied for anti-cancer properties. So much substance for such an unassuming sprout.

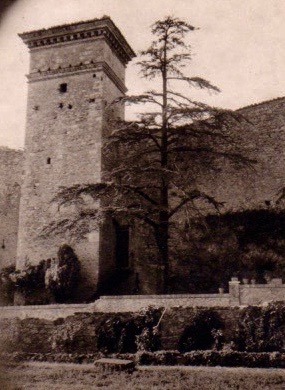

Germana’s wall of capers, in front of our tallest tower

The garden of my childhood, terraced below the house, was bordered by a long retaining wall. In the stones of that wall grew lush vines of wild caper. Had it not been for my Aunt Germana no one would have paid attention to them, and the pods would have blossomed peacefully into those large white flowers with fine purple pistils. For Germana, however, capers were an obsession. She kept an eye on the pods, and when they were ready, sun-ripened and about to open, she picked them while precariously balanced on a garden chair. Harvesting capers was a role that suited her and that no one challenged; it kept Germana occupied on the long days of summer.

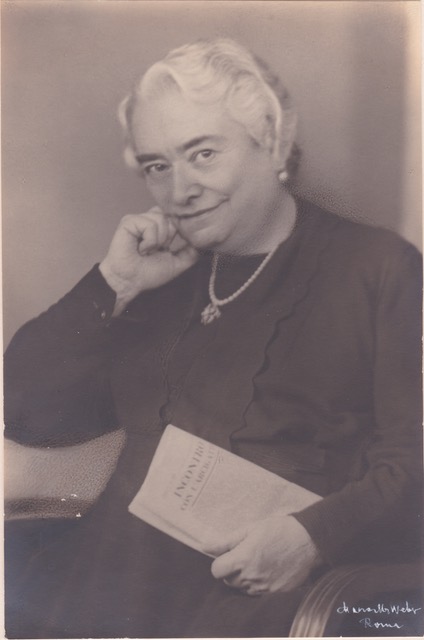

Once picked, the capers were strewn on wicker trays and left to dry on the roof of one of our medieval towers. When dry they were pickled and stored in glass jars in a cupboard. Germana’s dedication to this task was such that in the kitchen she earned the uncharitable nickname “Queen of Capers”. In reality, Germana had few pretensions. My great-grandmother’s unmarried younger sister, she was as submissive, modest, and simple-minded as the other was imperious, powerful, and cunning. I remember my aunt invariably dressed in a sort of thick cloth of indefinite color, buttoned at the front and knotted around her shapeless waist. She had a square face with heavy jaws, more than a trace of hair on her upper lip, and was almost completely bald (the price paid in a family that never ceased to intermarry). While attending to her humble task she scurried about releasing delicate farts.

One hot day the caper harvest resulted in a bad case of sunstroke. Germana had put a handkerchief on her head to protect her combed-over skull, but in the fervor of the work, perhaps stretching to reach the highest pods, it must have flown off without her noticing. She didn’t even hear the lunchtime gong that Rodolfo banged from the window with great indignation. She was found lying prostrate at the foot of the wall.

Aunt Germana |

Bisnonna Sofia |

Germana died in bed, asphyxiated by a faulty stove on Christmas Eve, 1967. She was over 90, an age not uncommon in the family and to which her meekness had contributed. The same fate did not, however, befall my aunt Gabriella (actually a distant relative) who shared Germana’s apartment. Their respective sleeping areas were separated by a simple curtain and, with the death of the neighboring aunt, Gabriella gained exclusive use of the entire suite. We children were too young to be exposed to the frightening mystery of death. We were taken away – Christmas presents and all – to the home of cousins, and when we returned a few days later there was no trace of Germana.

Me in the era of Germana