By Stanley Paul

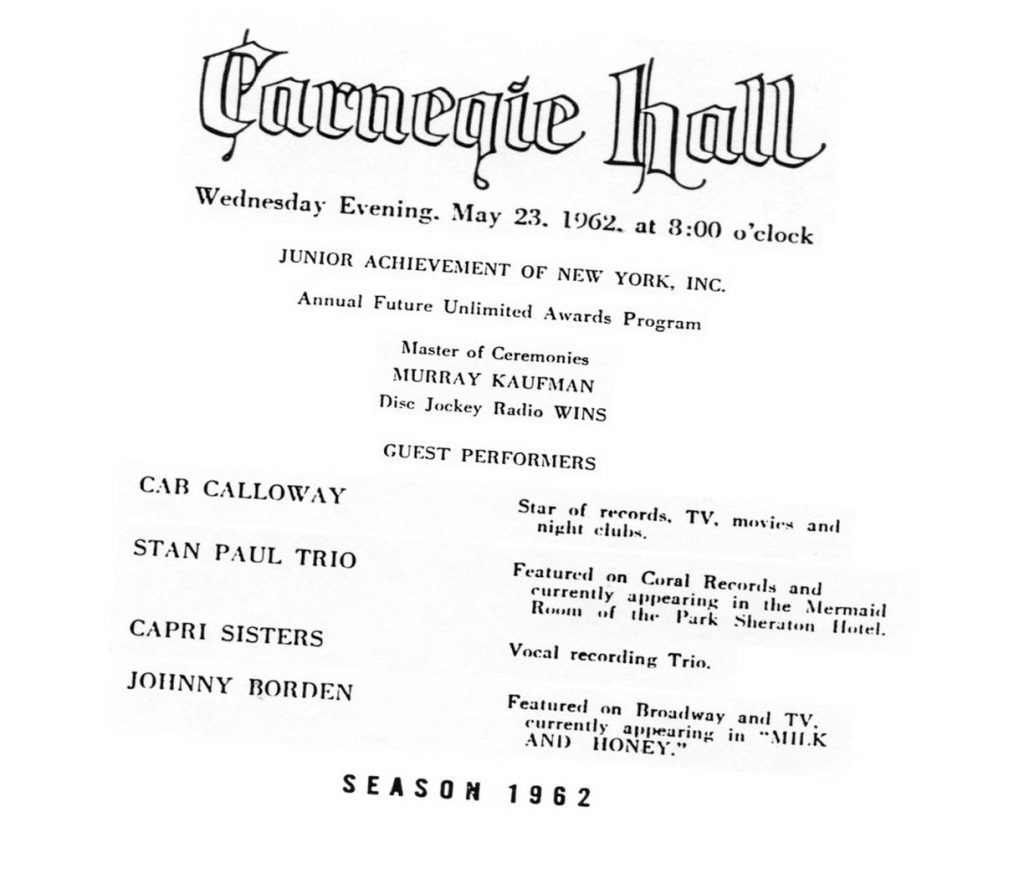

The movie My Geisha did not exactly thrill the critics, so after no more than a few weeks, my record was hardly getting any airplay. Decca did say, however, that they were very pleased with my performance and that they’d find something else for me to record soon. Though the movie and record hadn’t done particularly well, my publicity stunt had had excellent results. I was starting to get noticed, and soon received an offer to be part of a program that was being sponsored by the Junior Achievement Society of New York: I was going to perform at Carnegie Hall!

“Carnegie Hall!” Now that was one place I’d never in my wildest dreams imagined myself appearing. Carnegie had probably been in my parents’ fantasies for me back in the days when they’d been envisioning my future as a polished concert pianist.

Cab Calloway was on the bill, and for my bit, I’d been asked to play several selections from West Side Story. And I was nervous, to say the least.

As I stepped onto the stage, I was overwhelmed that I was actually going to perform here… my knees were knocking and my breath was short. Sitting down at the piano, I pressed my fingers down upon the keys and heard acoustics like I never had in my life. (And thankfully, because I was thoroughly familiar with the music, within a few minutes of starting, I calmed right down and had the time of my life.) The exhilaration of playing in such a magnificent place was simply indescribable; it was a night I’ll never forget.

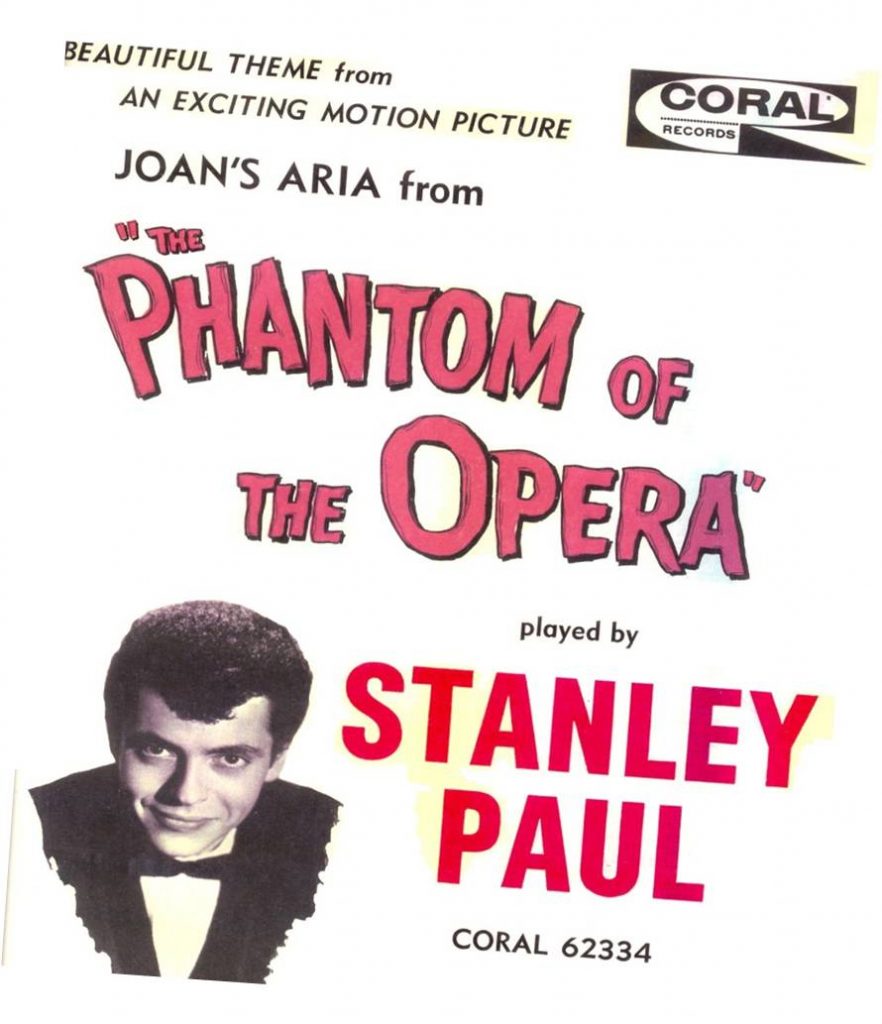

It wasn’t long after that Decca Records – because I was still under contract with them – wanted me to record a few new titles they had dreamed up for me… and I must say that, looking back, they were real doozies. The next one they chose for me to record was Phantom of the Opera, but not the version by Andrew Lloyd Webber… no, the 1962 British movie version. Decca even took out a full page ad in Cash Box and Billboard with my smiling face plastered across it!

The Phantom of the Opera bombed, just like My Geisha had before it. The people making decisions at Decca about what would succeed what wouldn’t were making some major errors in those days. Only days before, they’d turned down a group from Liverpool, a group that called themselves the Beatles. (I’m sure someone must have been fired for making that decision… Irving Berlin really knew what he was saying when he wrote, “There’s no business like show business!”)

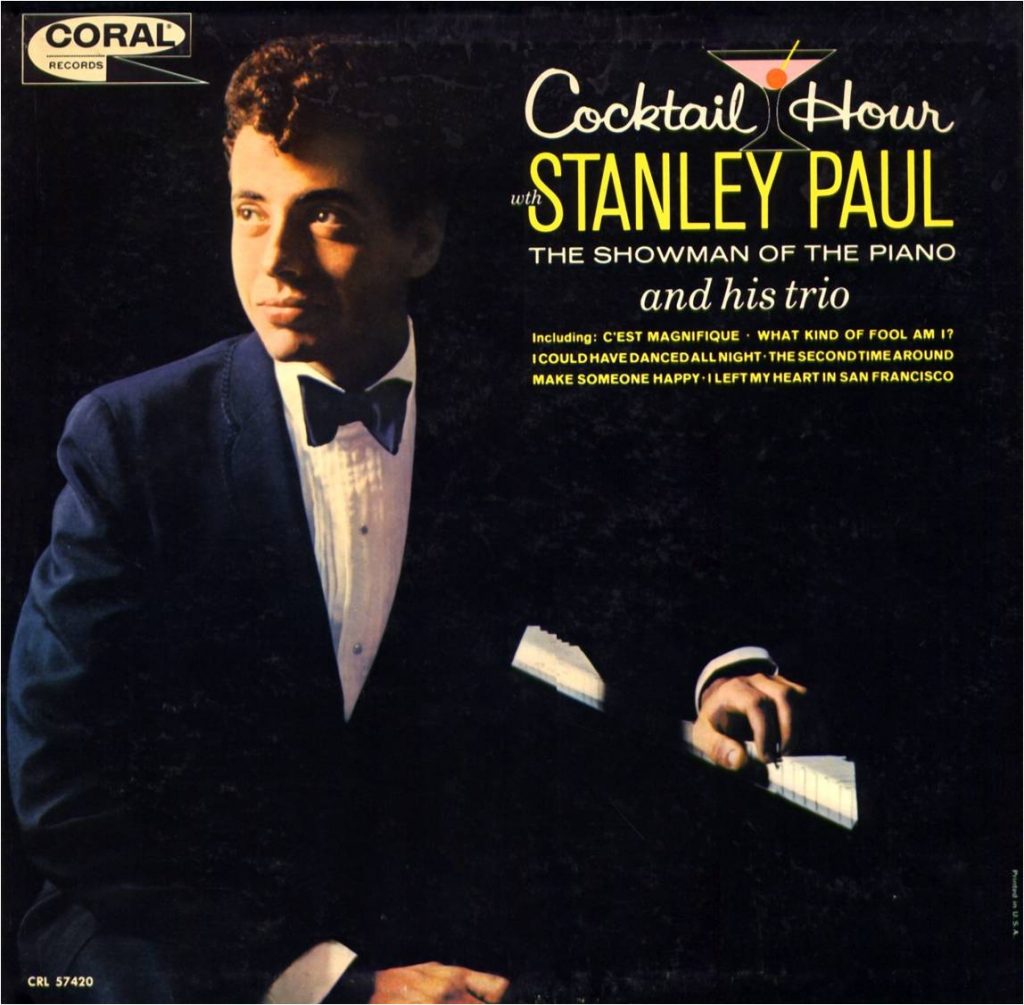

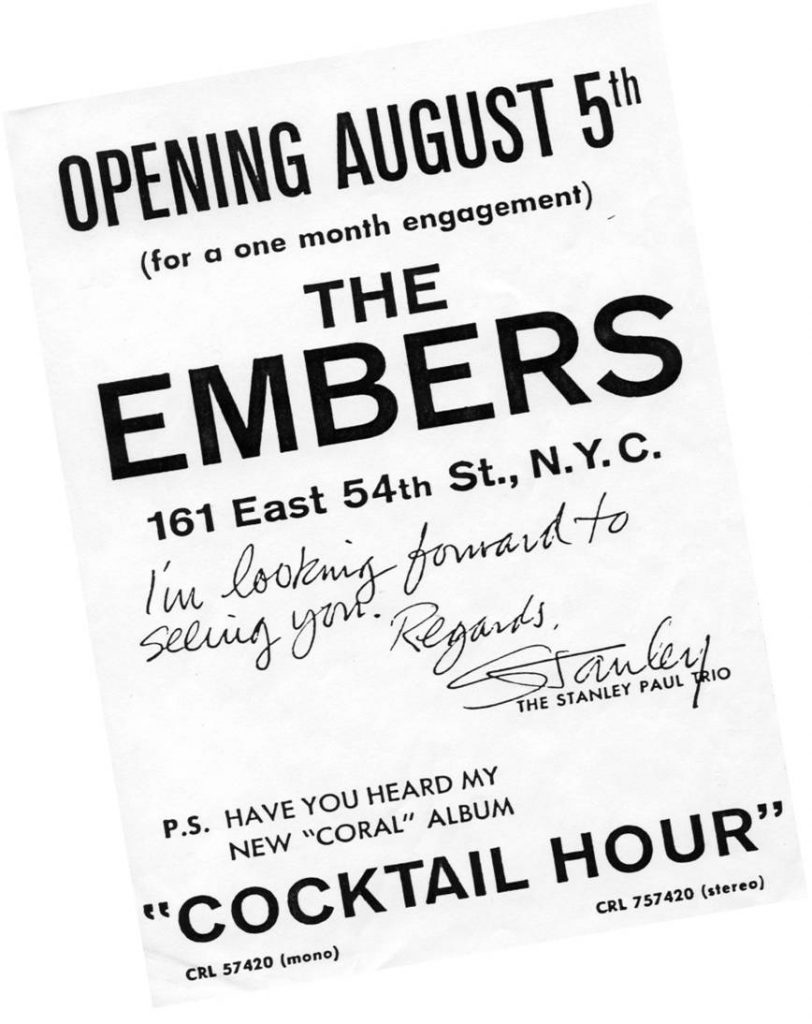

It seemed Decca came to the conclusion that I wasn’t going to be another Liberace, because they decided to produce an album featuring the Stanley Paul Trio. The setting was a candlelit nightclub with real live people in the audience, recorded late in the evening to make me feel more comfortable. It was called Cocktail Hour with the Stanley Paul Trio, and though it never made the charts, sales were less than embarrassing.

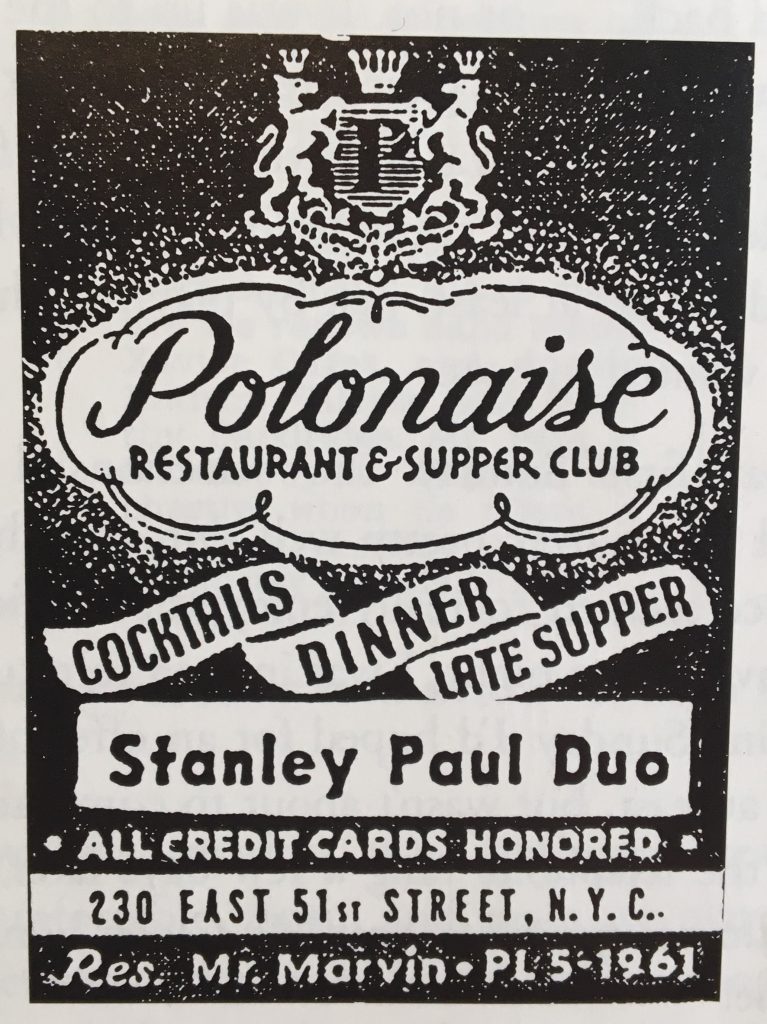

Throughout the end of 1962 and into the new year, my trio and I were booked for several New York clubs for short engagements… most of the names I cannot remember today.

Two of the clubs I performed in 1963… I even took a job as a duo (the tips were tremendous… and All CASH!)

Another club engagement I do remember was at a place called the Crystal Room on E 54th St. Late in the fall, we began here, and enjoyed a fairly uneventful run… except for one day that became unforgettable for me and every other person in the country. Ask anyone who was alive back then, and they’ll probably tell you exactly what they were doing on the day President Kennedy was shot.

I called the owner shortly after hearing the shocking news, expecting that the club would be closed that night. Mrs. Storch, whose son Larry would later become the co-star of the popular TV comedy show F Troop asked, “Why would we close? After all, he wasn’t related to us!” We were probably the only club in New York opened that evening, and of course the place was deserted except for the staff; I sure didn’t feel like playing.

In 1964, jobs were getting harder and harder to find, as fewer clubs were featuring any live entertainment. (A new word called discotheque had entered the vocabulary, and suddenly, all a club needed was a turntable and some loudspeakers.)

Meanwhile, Associated Booking had been trying to get me a booking at the Embers on E 54th St. It was New York’s premier jazz club, home of such well-known personalities as Dorothy Donegan and Erroll Garner. It was a real stepping stone, because if you did well there, you could get bookings in big name jazz places all across the country!

Finally, their efforts paid off, and on my opening night, everything seemed to click; the audience seemed to like me, there was lots of applause at the end of each set, and people even started singing along to the songs… in a jazz club! (The management didn’t seem to mind either, and when we left that night, I was on cloud nine!)

But the next day, I picked up a copy of the New York Herald Tribune, and I couldn’t believe what I was reading. The critics hated me, saying that I was “ruining the club,” creating a “sing alone atmosphere.” It was as if I’d organized an invasion of the hallowed ground of jazz! “And he never stops looking at the audience and smiling!” he wrote. “Smiling!” He ended the review with, “Solid applause at the end of his set… oh well.”

I learned later that Joe Glaser hadn’t been too pleased with the negative reviews; during lunch with another client, Erroll Garner, the subject came up of “what to do with Stanley Paul.”

“It’s obvious he’s no jazz pianist,” Erroll Garner pointed out, before adding, “but you know he would make a decent society band leader, between that smile of his and those medleys he plays.”

“You’ve got a point,” Mr. Glaser agreed. “I’ll see what I can do.”

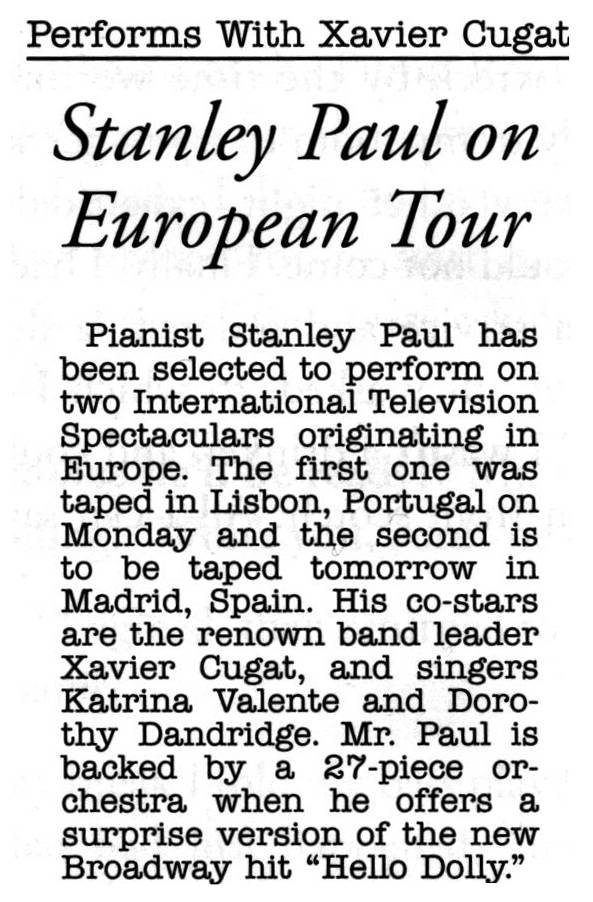

While Associated Booking was wondering what to do with me, some people who had seen me playing at the Embers thought my smile would be perfect for the show they were doing. It was a musical variety show called The Latin Touch, and was being filmed in Lisbon, Portugal! (I had to get a map out just to figure out where that was!) The famous Latin band leader Xavier Cugat was the emcee, but the production was to be distributed in Latin America, so it was unlikely anyone I knew would ever see it. But I was still so excited to be going to Europe.

I was paid $1000 (plus airfare), which was a fortune to me, for a week of my time in Lisbon, and then three days in Madrid for a follow-up filming. I ran out and bought a copy of Europe on Five Dollars a Day, determined to stretch my time overseas as long as possible.

When we finished up in Madrid, I toured Europe with no bookings at all for three more weeks, staying in cheaper and cheaper hotels as what was left of my thousand dollars quickly dwindled away. And then, finally, I went home.

A friend met me at the airport and took me home in her car, and thank God she did: by then, I had only thirty-seven cents left to my name! But I was so much older now it seemed to me, wiser for all the experiences… and poorer. I would need to look for work once again.

My new 8×10 right before starting at the Pump Room (1964)

One day, a few weeks later, I received a call from Mr. Glaser. He explained that the management of the Ambassador East Hotel were looking for a new band leader at a place in Chicago called the Pump Room, because the former band leader, David Le Winter, had just left.

“It’s in Chicago,” Mr. Glaser was saying. “Heard of it? The Ambassador East?”

I hadn’t heard of the Pump Room, but leading a band! Except for those few recordings I had made with Decca, I had had no experience with something like this. They wanted me to start in three weeks, and though in the whirlwind I had no idea what was happening, when I told my friends in New York about the opportunity, they couldn’t believe my good fortune. (And, when it finally sunk in, neither could I.)

It was a new direction, a real opportunity, and so with next to no experience leading a band, I packed up my life and flew to the Windy City of Chicago… and the rest is history!

No Fields Found.