By Russell Kelley

Russell and Lynn Kelley at Torres del Paine National Park

Russell Kelley is a retired lawyer who divides his time between his home town of Palm Beach and his adopted city of Paris, where he worked for 20 years. He and his wife Lynn are avid travelers. His great-grandparents, grand-parents and parents were all Chicagoans.

It may be the dead of winter in Chicago, but 6,633 miles to the south, it is summertime in Southern Patagonia. We spent a week at the End of the World in Chile’s Torres del Paine National Park to start the year. Here is our trip report.

The Chilean novelist Isabel Allende described her country as an island, surrounded by the Atacama desert to the north, the Andes to the east, and the Pacific to the west and south. The Chilean poet Pablo Neruda called Chile “the thin country” since it is squeezed between the Pacific Ocean and the Andes mountain range (cordillera). Chile’s 2,700-mile-long coastline ends at Cape Horn (Cabo de Hornos) at the southernmost tip of South America. The Southern Andes – part of the longest mountain range in the world, which stretches 4,300 miles along the entire length of South America – separates Chile from Argentina for 3,298 miles. If Chile is thin, Argentina is heavy-set, since it has nearly four times the surface area of Chile. Patagonia covers the southern half of Argentina and the southern third of Chile, with 90% of Patagonia in Argentina and only 10% in Chile.

As Tim Marshall, author of Prisoners of Geography (2015), says, “geography is destiny, and history is its interpreter.” And nowhere more so than in Chile.

Geography of Chile

Long and narrow Chile can be roughly divided into thirds.

The northern third is occupied by the Atacama desert, one of the driest places on earth and home to Chile’s mining industry. From 1883 to 1918, nitrite mining was the basis of Chile’s economy. Today, Chile is one of the world’s largest producers of nickel (along with Peru) and lithium (used in batteries for electric vehicles). The principal tourist destination in the Atacama Desert is the oasis town of San Pedro de Atacama, with excursions to the Valle de la Luna with its lunar landscape and the El Tatio geysers. With its clear skies and lack of light pollution, the Atacama Desert is also an ideal place for star-gazing.

The middle third of Chile is occupied by the Central Valley, where the capital Santiago is located. Due to its Mediterranean climate, virtually all of Chile’s agriculture is grown here, including its many vineyards (Chile is the fifth largest wine producer in the world). It is where all those delicious blueberries we find in supermarkets come from. Three quarters of Chile’s population of 20 million live in this area.

The southern third of Chile is occupied by Patagonia, the general area of mountains and steppes or pampas (grasslands) in the south of both Argentina and Chile.

Argentine Patagonia is nearly ten times the size of Chilean Argentina, with better tourist infrastructure and accessibility, and therefore more tourists. It features the towering peaks in Los Glaciares National Park, which includes the famous Perito Moreno Glacier and Mount Fitz Roy near the village of El Chaltén, along with vast open steppes, and long stretches of Atlantic coastline. The gateway cities are Bariloche in the north, in the Lake District; El Calafate in the south, on Lake Argentino near the glacier region, considered to be the central hub to Patagonia because of its air and road connections; Comodoro Rivadavia on the Atlantic coast next to the border with Chile, providing access to the eastern parts of Argentine Patagonia; and Ushuaia, the world’s southernmost city and departure point for many cruises to Antarctica.

The much smaller Chilean Patagonia is divided into two parts, occupying the lowest two of Chile’s 16 administrative provinces or regions.

Northern Patagonia occupies the Aysén Region along the west side of the bottom of the Andes. Its southern coastline was only mapped in 1831 when Charles Darwin and Captain Robert Fitzroy made their famous voyage on the Beagle. The interior of Aysén remained unexplored until late in the 19th century. Aysén is home to the Parque Nacional Patagonia, which was created by the late American Douglas Tompkins (1943-2015), climber, preservationist, and founder of the outdoor apparel company The North Face, who donated the land to Chile. It became a national park in 2018.

Southern Patagonia is south of the Andes mountain range in the remote region of Magallanes, Chile’s southernmost administrative region, which is cut off from Aysén and the rest of the country by a series of islands, fjords (senos) and glacier fields. Because of its remoteness, it is called “El Fin del Mundo” (The End of the World). That is where we went.

Magallenes

Magallenes is named after the Portuguese explorer Fernando Magellan, who was the first European to set foot on the southern end of South America in 1520. He encountered an indigenous tribe – the Tehuelches – who were much taller than the Europeans and called them “Patagóns” because they had big feet. (A giant called Patagón was a character in a popular novel at the time.) Rather than sail all the way around Cape Horn with its fierce gales, Magellan discovered a channel that substantially shortened the distance, but it still took him 38 days to force a passage through the 350-mile-long, narrow and treacherous strait that now bears his name. Magellan dubbed the ocean at the other end the Pacific because it was so calm.

South of the Strait of Magellan lies Tierra del Fuego (“Land of Fire”), so named by Magellan because of the campfires of the indigenous people he saw in its shores. Tierra del Fuego is comprised of many small islands and one big one – the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, the largest island in South America — south of the Strait of Magellan.

Five hundred miles south of Cape Horn is Antarctica, a large portion of which is claimed by Chile.

La Frontera

Around 1450, the Incas of Peru conquered northern Chile. They extended their empire as far south as the Central Valley, but further expansion south was stopped by the fierce Mapuche tribe. In 1533, the Spaniard Francisco Pizarro conquered the Incas. In 1541, Pedro de Valdivia followed the Inca Trail south, conquered northern Chile and founded Santiago, but he too was repelled by the Mapuches. The part of Chile south of the Biobío River at the southern end of the Central Valley next to the frontier city of Concepción was left to the Mapuche people, whom the Spaniards called Araucanians, for the next 300 years. It was known as La Frontera, or Araucania.

Throughout the Spanish colonial period and during the first decades after the independence of Chile and Argentina, Patagonia remained occupied by indigenous peoples in both countries. Credit: Ward, Protero, and Leathes, The Cambridge Modern History Atlas (New York, NY: The Macmillan Company. Downloaded from Maps ETC, on the web at http://etc/usf/edu/maps [maps #7582]

Following the independence of Chile, the so-called “Pacification of the Araucanians” took place between 1862 and 1881. The Mapuches were finally defeated and their territory was occupied by European settlers and incorporated into Chile. The Mapuche people, much reduced in number, are still by far the largest of the ten indigenous groups recognized in Chile and constitute the only significant ethnic minority in Chile.

Independence

During the colonial era, Chile was governed as an overseas territory of Spain, known variously as a “general captaincy”/“governorate”/“kingdom”, under the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Chile proclaimed its independence from Spain in 1818. The independence movements in Chile and all the other Spanish (and Portuguese) colonies in Latin America were inspired by the American War of Independence of 1775-82 and the French Revolution of 1789-99, both of which created republics in the place of monarchies, and by the conquest of Spain by Napoleon in 1808, when he placed his deeply unpopular brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne. (The Spanish called José “Pepe Botella” – Joe Bottle – because of his heavy drinking.) In revolt against French rule, many cities in Spain set up “juntas” of leading citizens to govern in the name of the deposed King Ferdinand VII. In the same vein, in 1810 Chile followed Argentina’s example and replaced the Spanish governor with a ruling junta made up of its leaders, thereby first asserting its right to self-rule, even if the junta swore undying loyalty to the Spanish king. The junta soon convoked a National Congress in another move towards possible self-government.

Spain attempted to nip this show of independence in the bud by invading Chile in 1813. Wars of Independence were fought on and off between 1813 and 1818, with the nationalist armies led by the Chilean General Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins (whose father was Irish) and the Argentine General José de San Martín.

European Immigration

After gaining its independence in 1818, Chile, like Argentina, encouraged European immigration. Many German immigrants came from the German Federation (a loose league of 39 sovereign states founded by the Congress of Vienna after the fall of Napoleon), and many Croats from the Austrian Empire, in the aftermath of the revolutions of 1848-49 that broke out in many European countries. German immigrants gravitated towards the Lake District. Later, Croatians headed for desolate Patagonia.

Immigrants also came from what was then the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (Ireland was incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1801), and later from Spain. Many British immigrants settled in the up and coming commercial seaport of Valparaiso. Later, other British immigrants became sheep farmers in Patagonia.

As a result of the surge of immigration from Europe, Chile naturally cultivated trade with Europe, and in particular with Great Britain. By 1875, 70% of Chile’s exports (mostly copper) went to Britain, which in turn supplied 40% of Chile’s imports.

The Border

The borders between Chile and its neighbors Peru, Bolivia and Argentina had never been clearly defined when they were all ruled by Spain, but border disputes arose soon after they became independent.

Between 1878 and 1884, Chile fought the War of the Pacific (also known as the Saltpeter War) against its northern neighbors Peru and Bolivia over Chilean claims to coastal Bolivian territory in the Atacama Desert that was rich in nitrates, or saltpeter, which were used in fertilizer for agriculture. Chile’s army and navy won the war, even capturing Lima. Chile took over Bolivia’s only province on the Pacific Coast, along with some land from Peru which was returned to Peru decades later. (Bolivia has been landlocked ever since.) Between 1881 and 1915, saltpeter accounted for 61% of the value of Chile’s exports and 43% of public revenues. But nitrate mining came to an abrupt halt upon the invention of synthetic nitrates in 1918.

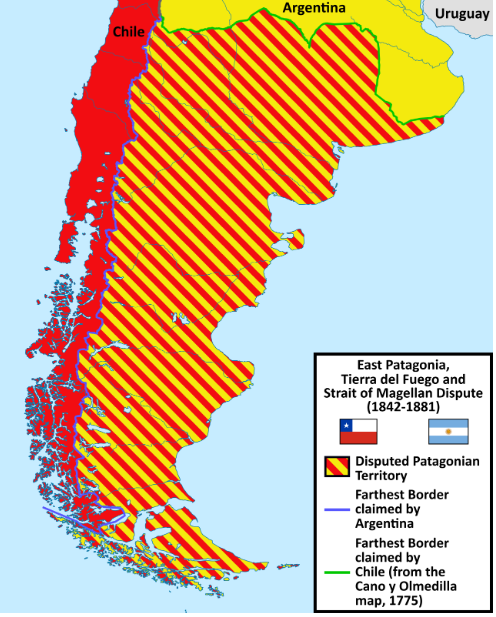

Credit: Janitoalevic. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4. International License

But the biggest border – and the biggest border disputes – were with Argentina, and mostly concerned the huge area of Patagonia, which had been left unexplored by the Spanish and was still inhabited by multiple indigenous tribes.

Prompted by the occupation of the Falkland Islands by Britain in 1833 and the explorations of the region by the British naturalist Charles Darwin on the Beagle in the 1830s, Chile claimed all of Patagonia, including the part on the eastern side of the Andes. To establish its claim to the strategic area around the Strait of Magellan, through which all shipping between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans passed, Chile established a fort (Fuerte Bulnes) on the Strait of Magellan in 1843, occupying territory claimed by Argentina. Argentina insisted that its border extended south from the last summit of the Andes as far as Cape Horn even though it never made any attempt to exercise sovereignty in Patagonia to support its claim. The Chilean settlement moved to nearby Punta Arenas in 1848.

During the War of the Pacific, when Chile was preoccupied with fighting Peru and Bolivia in the north, Argentina began to colonize Patagonia, compelling Chile to abandon much of its claim to Patagonia east of the Andes.

In 1881, after years of off and on negotiations, Chile and Argentina finally signed a treaty to resolve (most of) their border disputes. The treaty confirmed the Andes as the boundary between the two countries and partitioned the disputed region of Patagonia on this basis. In the south, below the Andes, straight lines were drawn to give Argentina the Atlantic coast, including the eastern half of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego where the near-mythical city of Ushuaia was founded in 1884, and Chile the Pacific coast, including the land on both sides of the Strait of Magellan, which was recognized as a neutral and freely navigable waterway.

Map showing the boundary between Chile and Argentina in Southern Patagonia including Tierra del Fuego. Torres del Paine National Park does not appear on the map; it is above the settlement of Cerro Castillo in red at the top center left of the map.

Sheep-farming

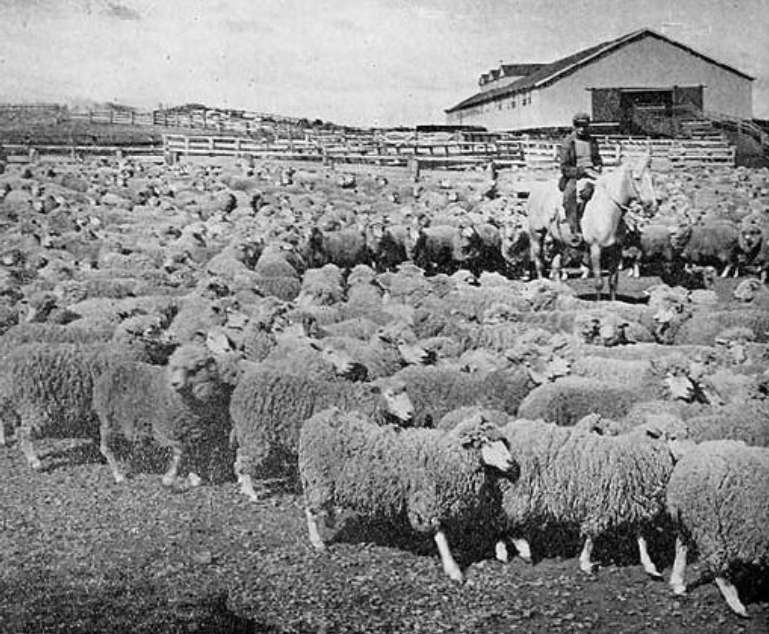

The pampas (dry grasslands in valleys between low mountains) or steppes of Magallanes were not suitable for agriculture, but some intrepid settlers thought they would support sheep-farming. In 1877, an English trader brought the first herd of sheep from the Falklands (las Malvinas) to Elizabeth Island in the Strait of Magellan. The experiment was a success and other European settlers soon followed. Enormous estancias (large ranches) were created, many owned by British immigrants. They brought in farm administrators from Scotland, England, Australia and New Zealand. Farmhands came mostly from the Chilean island of Chiloé, the second largest island in Chile.

Tierra del Fuego sheep ranch in 1942. Credit: Photo by Antonio Quintana (book author and copyright holder is Fernando Duran) – Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego, 1893-1943, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4211527

As everywhere else in the world, the European settlers forcibly occupied the lands of the indigenous peoples, in particular the Selk’nam in Magallanes. Between 1890 and 1930, the ranch owners carried out a campaign of systematic extermination, even offering a bounty for each dead Selk’nam.

Photo of Selk-nam people taken by Charles Wellington Furlong in 1917

Sheep-farming soon became the most important economic activity in southern Patagonia. At first, it was oriented towards wool production but with the development of industrial refrigerators it evolved towards meat exportation to Europe, and especially to the United Kingdom. The last meat packing plant, located just outside Puerto Natales, closed in 1974, the same year that the last full-blooded Selk’nam died.

Torres del Paine

In the northwest corner of the Magallanes Region is the Cordillera del Paine mountain range, which is separate from the Andes, newer and more jagged—like the newer and more jagged Dolomites are next to the Alps in Europe. (Paine [pronounced “PIE-nay”] means blue in the indigenous Tehuelche/Aonikenk language.) The mountain range is famous for the Torres del Paine, consisting of three distinctive granite peaks that reach up to 8,200 feet above sea level, and the Cuernos del Paine (“Horns of Paine”), all sculpted by glaciers.

The Cuernos del Paine. Credit: Lynn Kelley

Unlike the rest of Chile, the Cordillera del Paine is actually below and to the east of the Andes, which means that the only way to get there from Chile is by making a very long journey by road through Argentina. The only way to get there directly from the north of Chile is by making a three-day ferry trip from Puerto Montt to Puerto Natales, passing through the uninhabited islands and fjords that separate Magallanes from the rest of Chile, or by flying from Santiago or Puerto Montt to Puerto Natales. That is why the region is called “the End of the World.”

Torres del Paine National Park was established around the Cordillera del Paine in 1959. In addition to the famous Towers and Horns, the park also includes rivers, waterfalls, lakes and glaciers. It is the ultimate destination in Chilean Patagonia.

The three distinctive granite peaks comprising Torres del Paine on the right

On December 27, 1957, the first of the three Torres del Paine, the North Tower, was ascended for the first time by an Italian expedition led by Guido Monzino (1928-1988). A British expedition first climbed the Torre Central on January 16, 1963. A different Italian expedition made the first ascent of the South Tower on February 9, 1963.

The son of the founder of the Italian supermarket chain Stranda, Guido Monzino spent part of his fortune acquiring an estancia with 30,000 acres of land adjacent to Torres del Paine National Park. In 1977, Monzino donated the land to the park, establishing its present boundary. In 1978, the park was designated a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO.

Tourism in Chile’s Southern Patagonia developed gradually starting in the 1990s. Back then, intrepid tourists flew to Punta Arenas and then had to drive for six hours over mostly unpaved roads to reach the park. The small airport just outside Puerto Natales (now a pioneer town of 25,000 inhabitants principally employed in fishing, salmon-farming, and tourism), which is much closer to the park, opened to commercial jets only in 2016. There are now four flights a day from Santiago and Puerto Montt.

A guanaco on sentinel duty, on the lookout for pumas

It is 75-minute drive along a newly completed cement highway from Puerto Natales to the entrance to the park, a distance of 70 miles. In between are pampas with a few estancias, the occasional herd of sheep or cows, and groups of wild guanacos who are the meal of choice of the puma, the apex predator in Patagonia. Halfway to the park is the tiny town of Cerro Castillo near the border crossing to Argentina. It is a five-hour drive from Puerto Natales to the Argentine city of El Calafate, gateway to Argentina’s Los Glaciares National Park.

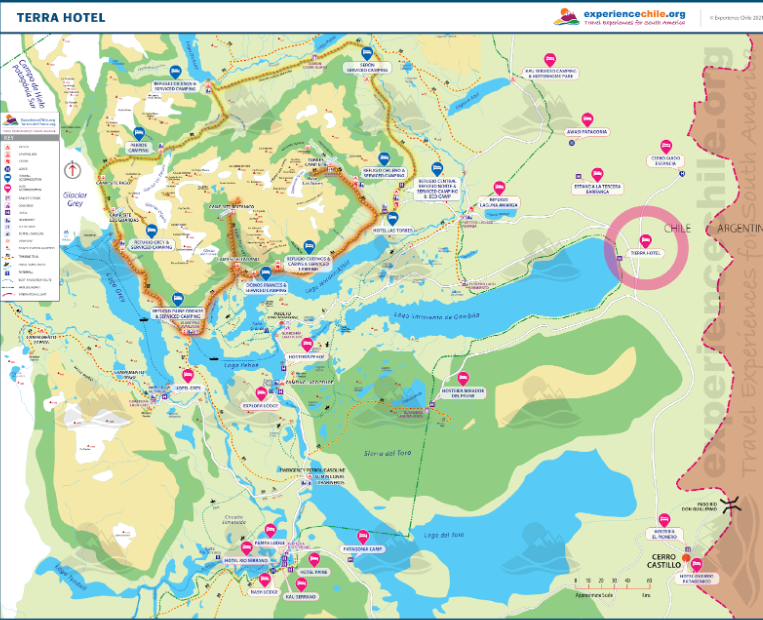

There is a wide range of lodges, refugios and campsites in Torres del Paine National Park, including the celebrated Explora lodge, which opened its lodge along Lake Pehoé in 1993. We stayed at the Tierra Patagonia lodge on Lago Sarmiento, which was a 30-minute drive from the entrance to the park. The striking structure was designed by Chilean architect Cazú Zegers in 2011 to blend in with the countryside. Both lodges are all-inclusive: room, board and activities.

Walking down to Lake Sarmiento from the Tierra Lodge, with the Torres del Paine mountain range in the distance

Hiking in Hunters Valley

Hiking to French Valley

People come to Torres del Paine to hike. There are hikes for all levels. The hard-core hikers take the eight-day O-trek known as “the Circuit”, which winds 68 miles around the entire park, or the four-day/50-mile W-trek (both treks are named after the shape of their routes) and stay in “refugios” (shelters) or campsites along the way. The most iconic hike is to the base of the three mountains that comprise the Torres del Paine, which involves a steep 7-mile climb which takes 4 hours up to the base, and the same back. (We skipped it.) But there are plenty of shorter hikes. Our favorite day-hike was from the Paine Grande refugio to the Campsite Italiano at the beginning of the French Valley (part of the W-trek), where the terrain alongside Lake Pehoé and Lake Skottsberg was rolling but not steep, with wonderful views of the mountains. It was, however, a long hike: around 5 miles each way. To get to the trailhead, you first have to take a very scenic, 30-minute ferry ride from Pudeto across Lake Pehoé to the Paine Grande refugio.

Map of Torres del Paine National Park. Note the paths of the C-trek and W-trek around the mountains, and the various hotels, refugios and campsites.

We also took a scenic boat trip from Hotel Grey across Grey Lake to Grey Glacier (unusually, the lake is named after the color of its water rather than after an early explorer or naturalist), and went for horse-back ride with an authentic gaucho wearing a well-worn red beret.

Grey Glacier. Credit: Lynn Kelley

Southern Patagonia is notorious for its high winds and fickle weather. While the park is open all year, most tourists come during the Chilean summer, between December and March.

Interestingly (and surprisingly), Torres del Paine is located at the same latitude in the Southern Hemisphere as London is located in the Northern Hemisphere.

Apart from the grandeur of the Cordillera del Paine mountains, what impressed us the most was the emptiness of the vast expanses, with few animals, and even fewer people. It truly did feel like the End of the World.

P.S. Our Chilean guides added immeasurably to our experience. Without exception, they were delightful, well informed (most had studied “ecotourism” at university), and spoke excellent English. They did, however, have a hard time pronouncing “sheep”, “ship” and “cheap”.