By Elizabeth Dunlop Richter

The Dia Art Foundation is not well known outside the art world, but once you experience Dia Beacon or one of its other projects, it’s unforgettable! My husband Tobin and I were able to do just that on a recent road trip that took us to the Hudson River Valley. To be sure, there are well-known artists on display here: Andy Warhol, Sol LeWitt, Sam Gilliam, and Gerhard Richter. The works here, however, are, in the words of the museum’s publication, “uncurbed by the limitations of more traditional museums and galleries.” This was the founders’ concept. Philippa de Menil, daughter of Houston arts patron Dominique de Menil and heiress to the Schlumberger oil fortune, joined art dealer Heiner Friedrich (whom she would later marry) and art historian Helen Winkler to create the foundation in 1974. In the words of its mission statement, they were “committed to advancing, realizing, and preserving the vision of artists.” The goal was impressive. The visions they supported were too large, too unmanageable, and too impractical for the expected museum/gallery setting or too difficult to fund through traditional means.

Dia Beacon photo credit

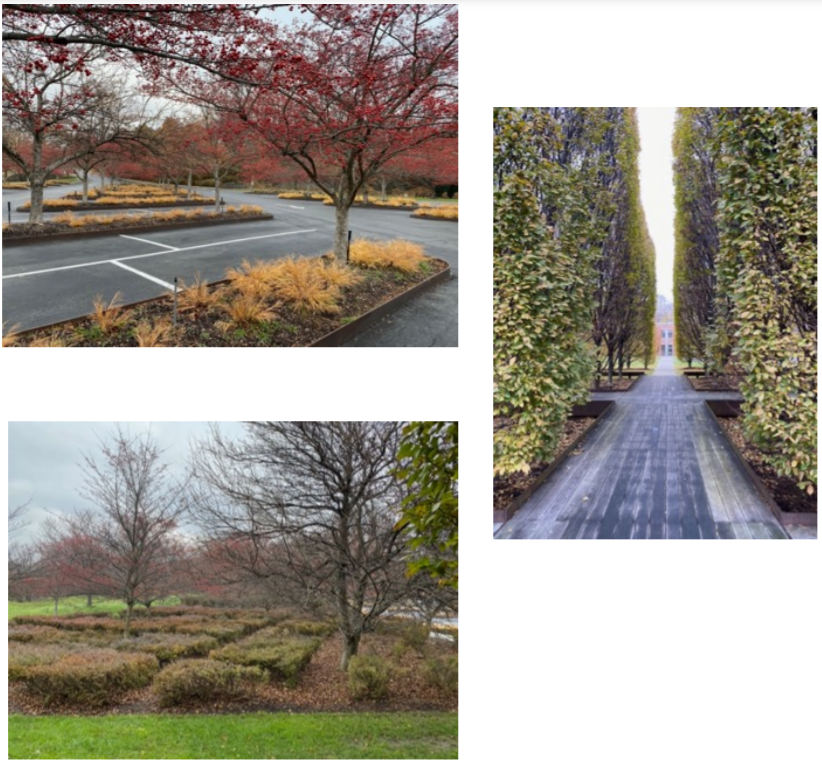

ample room for special exhibits. Its wide-open spaces and 34,000 square feet of skylights letting in northern light were the foundation for a dramatic renovation by artist Robert Irwin and architects Alan Koch, Lyn Rice, Galia Solomonoff, and Linda Taalman, then of OpenOffice. We arrived shortly before opening on a chilly November morning and were able to explore the handsome landscaping on its 31 acres along an icy, grey Hudson River. Even the parking lot with its red-leafed trees and golden grasses was handsomely designed.

Sculpture by Chicago Art Institute-trained John Chamberlain fills a spacious gallery |

xxx |

A portion of Andy Warhol’s Shadows series

Richter contemplates Richter

Oversized, conceptual art with the kind of expansive vision supported by Dia is bound to elicit a wide range of reactions.

Because their families may both have ancestral roots in Meissen, Germany, my husband Tobin Richter has always been intrigued with Gerhard Richter’s career. The works created by the internationally known artist specifically for Dia Beacon, Six Grey Mirrors, however, did not impress him with Gerhard’s artistic prowess. The exhibit consists of huge, plain enameled glass panels, hung at different angles to reflect windows, walls, ceiling, and the visitor. Dramatic, yes. Taking advantage of the ample space, yes. Idiosyncratic, yes. Gerhard himself has said the series is “the welcome and only possible correlative for indifference, apathy…formlessness.”

My husband, a painter too when he’s not lawyering, was similarly unimpressed by Robert Smithson’s Map of Broken Glass (Atlantic), which he felt just dangerously took up floor space. Smithson is known for, among other works, the 1979 Spiral Jetty, an earthwork that Dia maintains on the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Dia’s brochure explains the Map of Broken Glass (Atlantic) as “a shimmering collapse of decreated sharpness arrested by the friction of stability.” My personal favorite of Smithson’s pieces is his 1969 Leaning Mirror, which impressed me with its simplicity, elegance, and contrast of sharp and permeable surfaces. It’s another of his “indoor” earthworks that, in the words of the museum, “address processes of accumulation, displacement, and entropy in order to reveal the contradictions of our visible world.”

Robert Smithson’s Map of Broken Glass (Atlantic)

Robert Smithson’s Leaning Mirror

All artwork does not occupy vast space at Dia. Many galleries were designed to enhance specific individual works. Seemingly about to burst from its gallery, Richard Serra’s massive Union of the Torus and the Sphere expresses his interest in volume, movement, and space. The unusual shape gives the visitor an off-balance sense of instability as one explores its curving angles.

Richard Serra’s Union of the Torus and the Sphere

A similarly tightly enclosed work encompasses a huge stone snugly tucked in a box on the wall. Negative Megalith was created by Michael Heizer and reflects his focus on ecology, archeology, and the natural landscape.

Michael Heizer’s Negative Megalith

But Heizer also pursued what one could call negative sculpture. Turning the corner of the gallery, I was stunned to see a dramatic series of works also by Heizer that could be imagined only at Dia Beacon. Four deep, geometric pits, titled North, South, East, and West, were commissioned as a complete work for the permanent collection.

Michael Heizer’s North, South, East, and West

Rather than dig a massive hole, Michelle Stuart chose to stay on the earth’s surface for her representation of a brick quarry in New Jersey. In sharp contrast to the metallic hard edges of industrial materials, she applied panels of paper to make rubbings of the land itself. With a background in mapmaking for the US Army Corps of Engineers, Stuart used a muslin-backed rag paper to capture the earthen colors of Sayreville Strata Quartet. Soil and pebbles were rubbed into the fabric of the paper itself, depicting the different colors of the quarry layers.

|

|

x |

Whimsy and lively color are not missing at Dia Beacon. Charlotte Posenenske’s charming cardboard and metal tubes reflect her dedication to democratic, participatory construction design. For this installation, she invited twenty participants to workshop this playful series of shapes that reminded me of our son’s childhood cardboard box constructions.

Among the work collected in the museum’s first ten years, Dan Flavin’s colorful glowing fluorescent tubes are easily recognized as his preferred medium. In addition to his collection here, Dia created the Dan Flavin Institute, now Dia Bridgehampton, in a former firehouse and church.

Light installations by Dan Flavin |

x |

While I was delighted with the overall impact of Dia, I do have my favorite exhibits (and I must confess I have touched on just a limited selection of what’s here; we did not even get to the entire museum on both levels).

In one of the long galleries, I discovered Mario Merz, an artist with whom I was not familiar. He channeled his fascination with the Fibonacci Progression in unusual ways, in his words, “to create relationships with it.” The progression, which forms a sequence in which each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers, lies at the foundation of his 8,5,3 installation of three integrated igloo-like shapes inspired by the Inuit. Three half-spherical structures made of tar, glass, and twigs respectively, reflect the favored ratio. The work features neon rods protruding through the glass dome. A red neon sign reading “objet cache-toi” (object, hide yourself) adorns the largest twig structure. Merz’s mysterious meditations on natural, animal and industrial objects are expanded through the mathematical formula.

Mario Merz’s 8,5,3

For pure exuberance, Sam Gilliam’s vibrant abstract swaths of color take on new energy when he moves beyond the flat canvas. Initially, he added a beveled edge to his canvases to create a more three-dimensional effect. Other loose painted canvases hang from the ceiling, enlivening the sparkling blue, rose, silver, and yellow hues with a sense of movement.

|

x

x x x Sam Gilliam

|

I am sure I walked off a few hundred calories as I covered the length and breadth of the museum. It far exceeded my expectations in spaciousness, artistic expression, and scale. Our visit to Dia Beacon has inspired us to track down some of the other Dia Art Foundation experiences for future trips. These include Max Neuhaus’s sound texture Time Square (on the triangular island at Broadway and 45th St.), Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field in western New Mexico, Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels in Great Basin Desert, Utah, and the previously mentioned Spiral Jetty. The Dia Art Foundation has survived rocky years of diminished resources and board turnover. New money has been added to its coffers. We can be thankful that generous philanthropists can see beyond traditional museum walls to provide such stimulating environments.