By Judy Carmack Bross

Guest Curator David Hanks with Sarah Holian, to his left, the curator of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Chicago, to his right, Jennifer Gray of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, and Ken Tadashi Oshima, Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington.

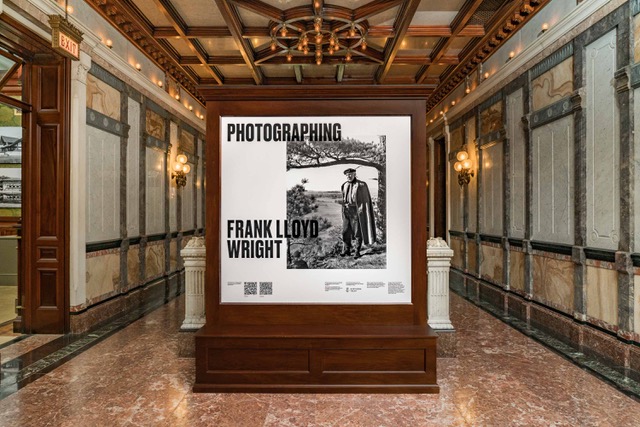

“When I first thought of creating an exhibition on Wright’s own photography and the photographers who documented his architecture, I found there was no book, no exhibition out there. Frank Lloyd Wright had a fascination with photography, viewing it as a hobby as well as a way for his architecture to reach a broad public.”—David Hanks, on curating “Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright,” his show as Consulting Curator at the Driehaus Museum which runs through January 5, 2025.

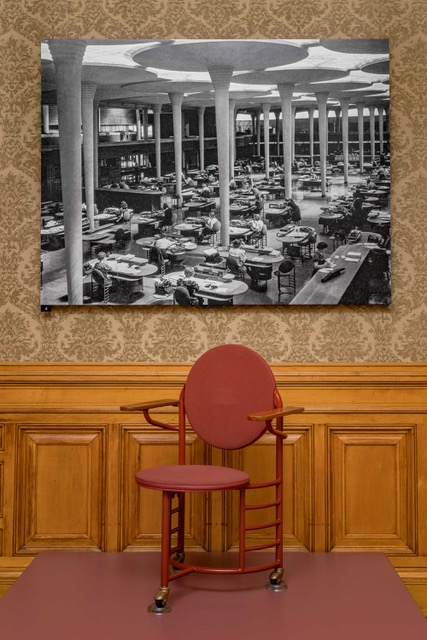

On a recent Wednesday night at the Driehaus Museum “Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright,” the first exhibition to present the fascinating and unexplored topic of Wright’s own early photography as well as images by the leading photographers who documented his work, drew a crowd of the architect’s fans who treated America’s foremost architect as a favorite hometown boy. Admiring his photos of his first wife Catherine and son and of his Oak Park Home and Studio placed close to a photo of Wright on his tree-lined terrace there, looking so different than the terrace does now on the busy Chicago Avenue. His stunning photo of morning glories, which used a popular photographic printing technique of the time known as collotype, also drew praise from visitors. In the collotype process, a negative is projected onto a plate coated with light-sensitive gelatin that hardens and then ink is applied.

A black and white newsreel of the architect speaking about why his Imperial Hotel survived the Tokyo earthquake captures the Wright persona.

“He had tremendous self confidence and knew that he was a great architect,” Hanks said. “But he struggled during his life, both financially and with his marriages. He often found he needed to borrow money.”

With photos that appeared in publications such as LIFE magazine and Architectural Forum, the exhibition offers insights into how photography influenced public perception of his work. In addition to the architectural photos, the exhibition also includes examples of Wright’s decorative designs, demonstrating his concept of design unity.

Hanks worked closely with the Driehaus Museum team and two well-known Chicago experts- Tim Samuelson and Eric O’Malley. Much of his research was done in New York, where the Avery Library at Columbia University holds Wright’s archives, and the Museum of Modern Art is the repository for his models. These collections are owned jointly by the Avery Library and the Museum of Modern Art.

A St. Louis native, Hanks came to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1969, where he served as a Curator in the Decorative Arts for five years. “At the Winterthur Summer Program, I had studied eighteenth-century decorative arts, which was then the Art Institute’s American decorative arts focus. I became more and more interested in the 19th and 20th century because of all the Chicago material I discovered. Members of the Antiquarian Society helped build the Art Institute’s collection of Wright and other Chicago architects. I remember Mrs. Philip K. Wrigley donated a Frank Lloyd Wright window and Zibbie Glore made possible the acquisition of architectural fragments.”

In 1980, Hanks was invited by the Stewart Foundation in Montreal to assemble a collection for the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts, and he continues to divide his time between New York and Montreal to continue his work with the Foundation. “It’s an hour’s flight, much quicker than the commute my friends take out to the Hamptons,” he said.

“My Chicago connection will always be a strong one. It has been great working on shows at the Driehaus Museum with the help of friends whom I worked with when I was at the Art Institute- such as Tim Samuelson and John Vinci, who know so much about Wright and Chicago’s architecture,” he said.

David Hanks was Guest Curator for the Hector Guimard exhibition at the Driehaus Museum

“The Driehaus Museum is so well located, and its upstairs rooms are perfect for a range of exhibition topics, including decorative arts and photography,” Hanks said. “Like Chicago’s Glessner House, and small museums in Paris such as the Musée Rodin, it adds to the cultural richness of a city to have these fine smaller museums.”

We asked Hanks to tell us more about “Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright:”

CCM: Tell us about Wright as a photographer.

DH: The concept of Wright as a photographer had not been adequately explored in previous exhibitions. This exhibition devotes an entire theme to the architect’s own photography, but there is still much to explore about the photographs he took. Wright was very interested in exploring the possibilities of this relatively new technology; he photographed the Hillside Home School, owned by his aunts, for use in marketing the school.

CCM: What can we learn from architectural photography about not only the architect but also about the times?

DH: It is always fascinating to see that photography then is very much like today, though the technology has changed. In Wright’s own photography, we see him documenting his trip to Japan, taking photos of his family members, often in groups, recording details of nature that interested him, and also creating what are today called selfies.

CCM: How did you choose these architectural photographers and are there certain things the viewer should look for as they view the show.

DH: We chose the leading photographers of each period, and only those who had a direct relationship with Wright. The architects worked with his photographers, describing what he hoped to achieve in the images.

Docents and staff at the exhibition

CCM: I had a great talk with the docents there last night and they loved when you gave them the tour. What is the role of the docent and how should the visitor utilize them?

DH: The Driehaus Museum’s tour guides provide an important personal interaction between the visitor and the works on display. They are sensitive to each visitor’s level of knowledge and engage with visitors, accordingly, providing an interactive educational experience based on the interests and knowledge of the visitor.

CCM: Do you have a favorite photo and how did you ever began to choose for the exhibition?

Wright’s first wife Catherine with son Robert. Photographer: Frank Lloyd Wright. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, Chicago

DH: I had always been drawn to the photo of Wright’s wife Catherine reading a book with their son – the architectural composition of the photo is particularly noteworthy. There were many photos to choose from, but we chose the photographs that we felt best represented Wright. For example, we had to choose only a few from the many portraits of Wright, and we sought one self-portrait.

CCM: What was the process of choosing the photos?

DH: The process required considerable research in archives and publication to locate the available photos to consider, before deciding which of Wright’s commissions to focus on, and finally the best photo of each building.

CCM: What can we learn about modern architecture here?

DH: Because the exhibition looks at Wright’s work over his entire lifetime, it presents the evolution of Wright’s architecture from his early work to his final masterpiece. Visitors can learn about the history of his work from the 1890s to 1959, which are arranged in a roughly chronological sequence, as presented through his photographers.

CCM: What has been your role—and I know that it has been a long-lasting one—with the Driehaus, and what makes it an ideal space for this exhibition?

DH: My role is as a Consulting Curator for this exhibition. The Driehaus Museum provides the ideal space for exhibitions such as this one because it offers an intimate space in a series of galleries (actually the former Nickerson family’s bedrooms) with a warm background colors.

CCM: What does it say about Frank Lloyd Wright the man?

DH: We included a Timeline to give a sense of Wright as a man – which combined personal as well as professional information about his life. He is considered the greatest American architect, but as the facts of his personal life show, he was not perfect.

CCM: How can we as Chicagoans explore best Wright’s legacy?

DH: Chicagoans have the unique opportunity to see Wright’s built work in person, thanks to organizations like the Frank Lloyd Trust, which is devoted to preserving his buildings in Chicago and making them available to the public.

For More information about “Photographing Frank Lloyd Wright” at the Driehaus Museum visit driehausmuseum.org

Opening night photos by Robin Subar.

Installation photos by Robert Chase Heishman

Author Photo by Jessica Tampas