By Cheryl Anderson

“It irritates me when I hear people say that I’ve been lucky. No one has worked harder than me.”

—Chanel

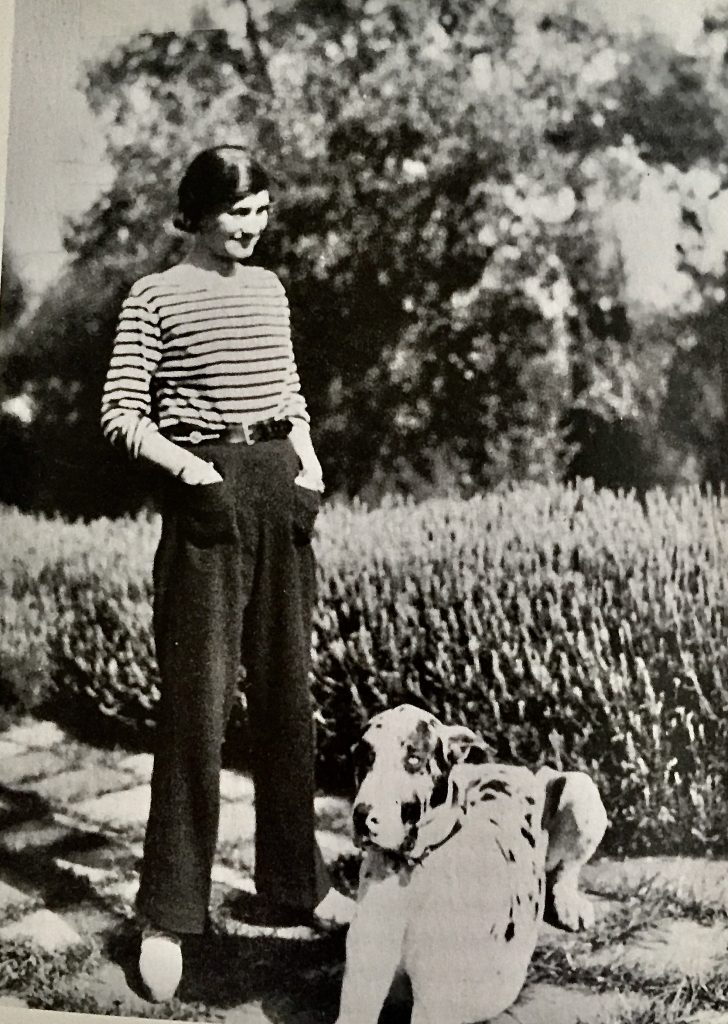

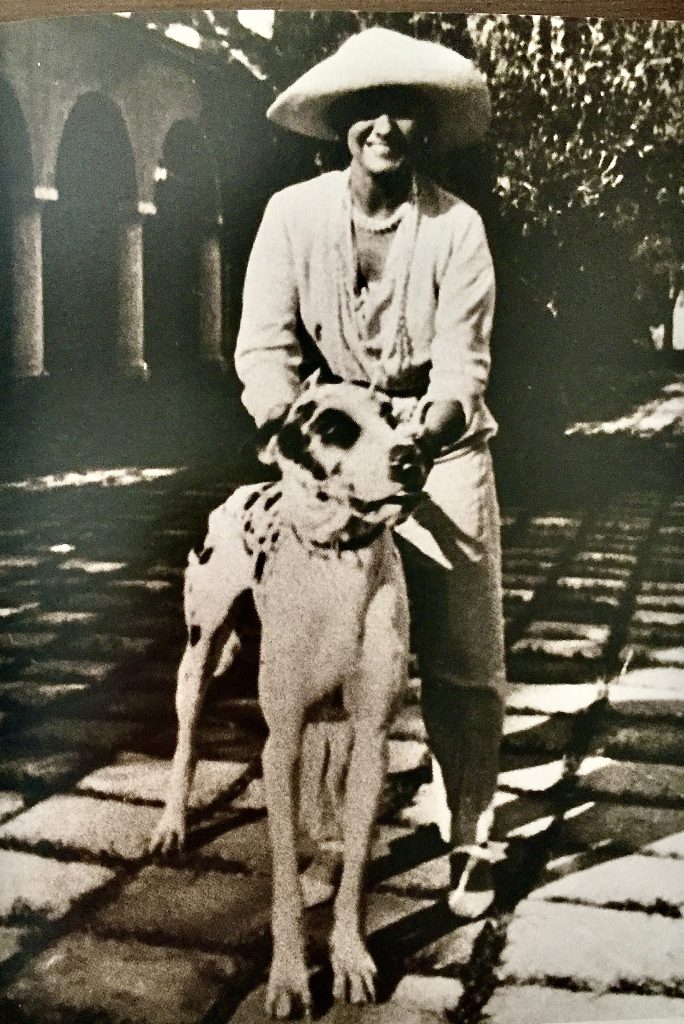

Chanel in her striped marinière top with Gigot at La Pausa 1930

Coco Chanel loved the Côte d’Azur. She wanted a place to call her own, to be in the place she adored. For just a while, now and then, a place away from her busy life, and to take the scissors, hanging from a ribbon, from around her neck. La Pausa would become her refuge dans le beau monde de la Côte d’Azur—it became the center of her summer life. Although the Americans were instrumental in making summer the high season around 1923, La Pausa became part of the Côte d’Azur’s high society. She was instrumental in making it a lifestyle—the playground for the rich and famous, the place to be. La Pausa was her residence from 1929-1953.

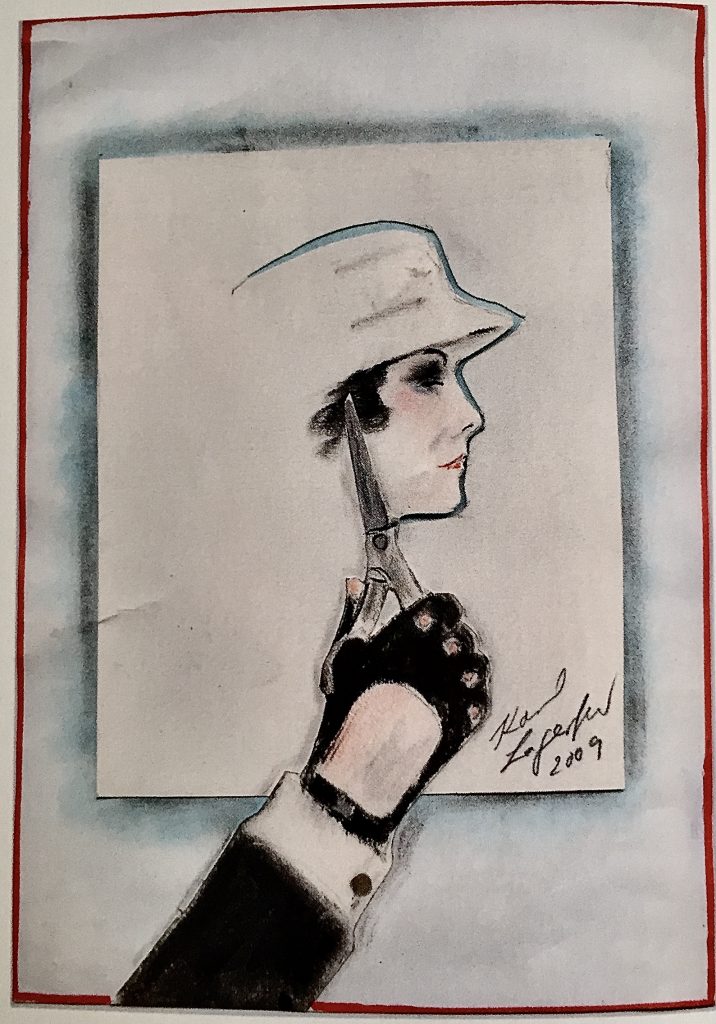

Chanel, by Karl Lagerfeld.

You may wonder why I would mention scissors? Justine Picardie recounts: “When Gabrielle Chanel stepped into her realm at Rue Cambon, her assistant would hang a long white tape around her neck with Mademoiselle’s special scissors threaded through it, like a ceremonial necklace. Other pairs of scissors were always within her reach—silver and gilt ones arrayed in her apartment and in rows on her dressing table, lying beneath an icon given to her by Stravinsky…In old age, when Chanel was showing Claude Delay her gold boxes from the Duke of Westminster, she pointed out the coat of arms engraved on the top. If she were to mark her own emblem next to his, she said, ‘I would add my scissors.’ …she still wielded her scissors on a daily basis to shape and remake her creations. ‘What you have to do is cut’, she said to Delay.” Chanel is quoted as saying: “Costume designers work with a pencil: it is art. Couturiers with scissors and pins: it is a news item.” I gather from her quote, her use of scissors was often written about. Most everything Chanel did was written about in the newspapers, down to the scissors.

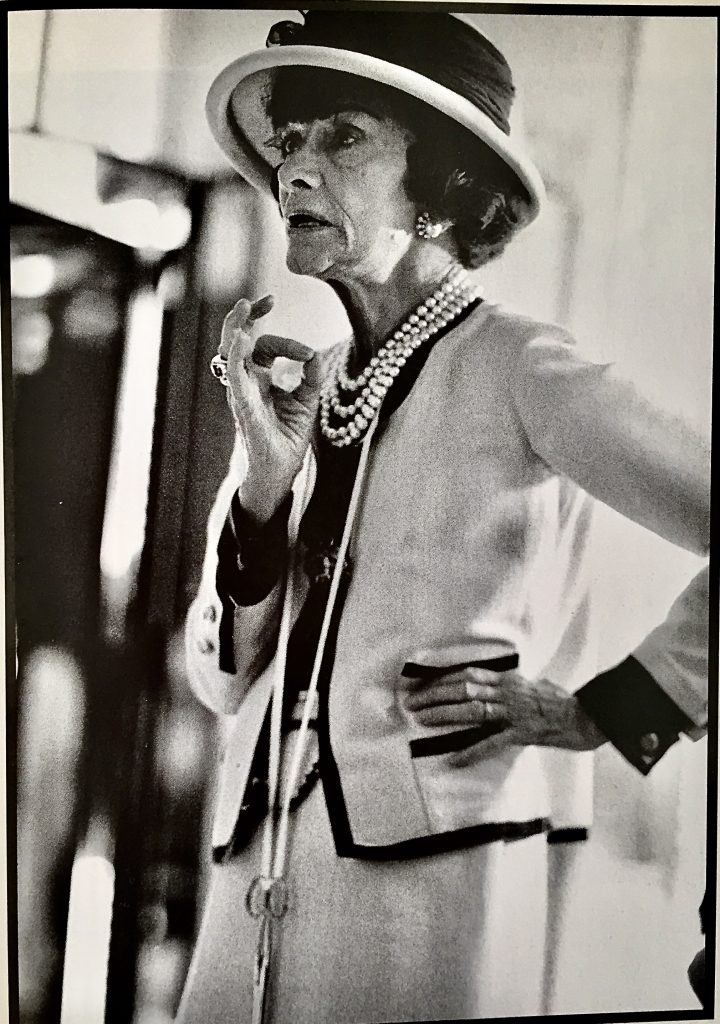

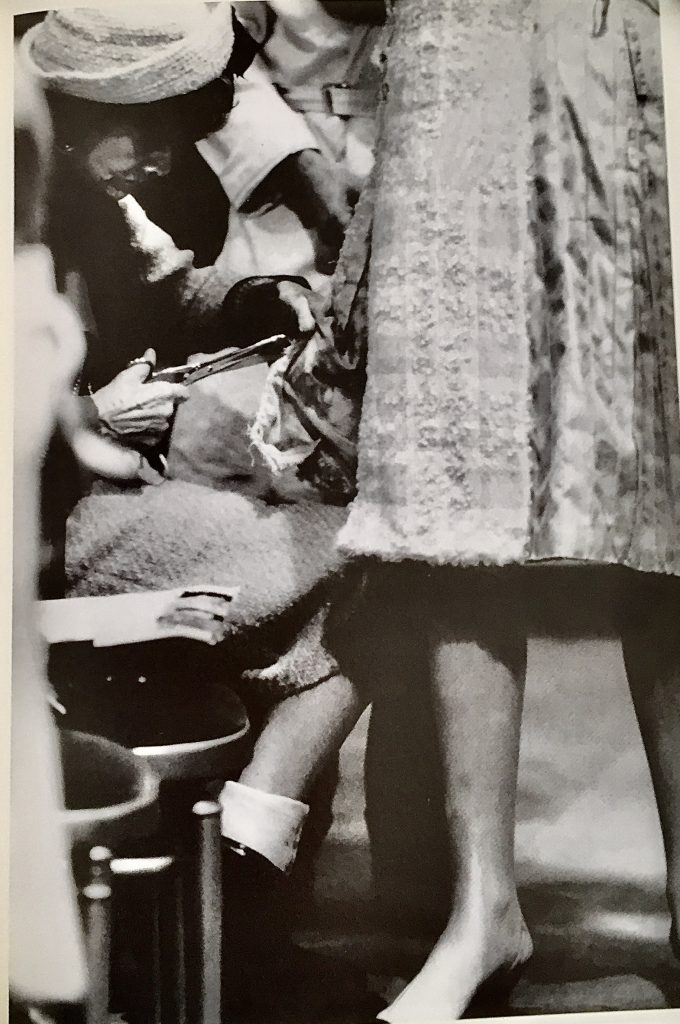

Chanel with her scissors on a ribbon around her neck.

Chanel first saw the property, where she would build La Pausa, while sailing the Mediterranean with Westminster on his yacht the Flying Cloud, December 1927. The property was 180 meters above the sea in the small village of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in the exclusive neighborhood of La Toracca. It overlooks Menton with sweeping views of the bay—the Italian border to the east and Monaco and its bay to the west with the Alps Maritime behind the property. Originally, there were three existing buildings on the property that were transformed into the main house with two small cottages for guests. It was less formal than other houses in the South of France.

Chanel on the deck of the Flying Cloud with opera singer Marthe Davelli 1930.

Picardie states: “La Pausa was entirely her creation, a graceful villa on the French Riviera at Roquebrune, high above the wooded promontory of Cap Martin with a commanding view of the Mediterranean… In February 1929, Coco Chanel signed the deed of sale for the five acres of land upon which La Pausa was to be built. The general assumption has tended to be that Bendor bought the plot of land and financed the construction of La Pausa, but it was Chanel’s name on the deed, and the 1.8 million francs in payment came from her bank account, rather than the Duke’s.” The property had been the hunting grounds of Monaco’s ruling family, the Grimaldis.

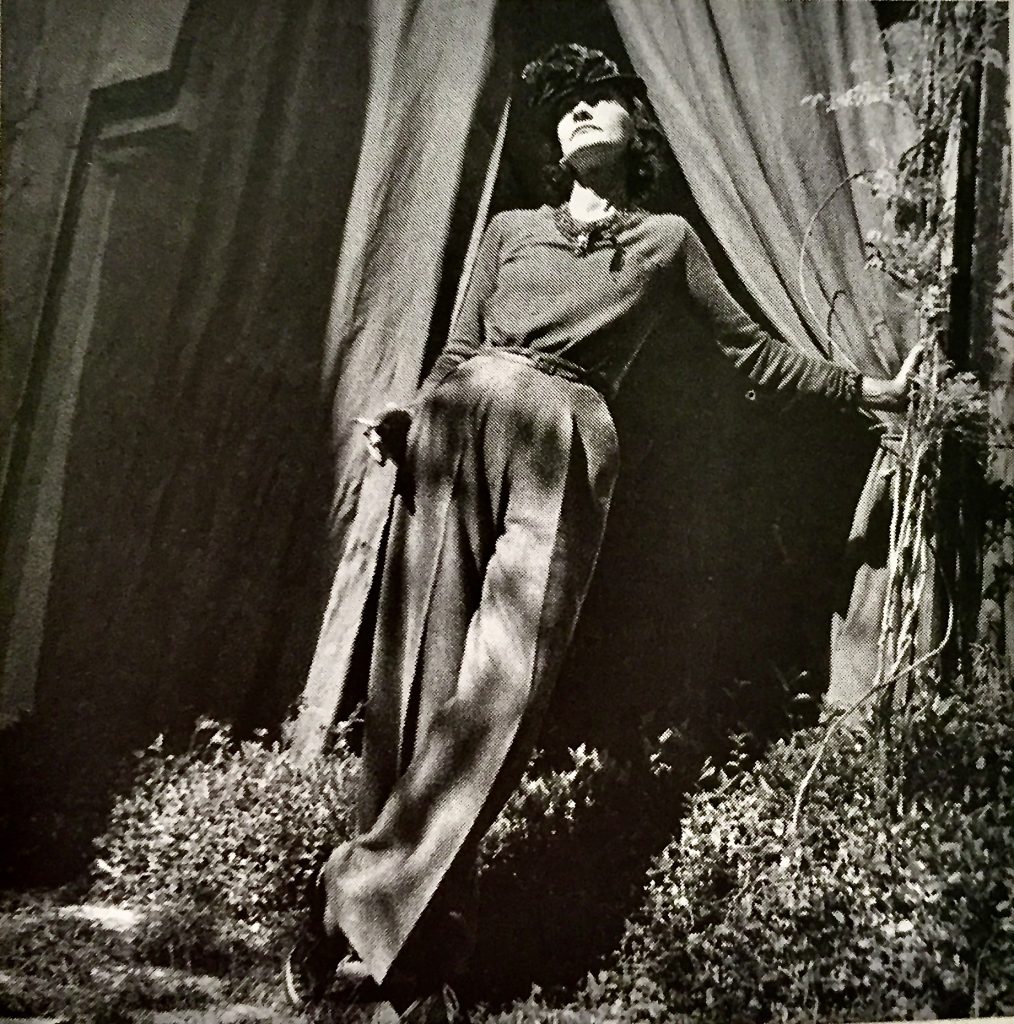

Chanel in the gardens of La Pausa striking a glamorous pose. Roger Schall 1938

Charles-Roux points out: “In 1928 Chanel traveled to the heights of Roquebrune and made herself a present of an olive grove and a view of extraordinary beauty overlooking the Mediterranean. A royal acquisition, it consisted of a summer house—her first vacation home.”

La Pausa was proof of the independence she so desired. She bought the land, signed the deed, designed everything, and had the villa built exactly how she imagined. In American Vogue, March 1930, the headline read: “ ‘Mlle Chanel’s House’. ‘There is no doubt that Mademoiselle Gabrielle Chanel is a person with very rare taste’, declared Vogue, ‘and it is therefore not in the least surprising that she has built for herself one of the most enchanting villas that ever materialized on the shores of the Mediterranean…To begin with, she chose the site very carefully…On the left is all the lovely sweep of the Italian coastline, and on the right, the Rock of Monaco and the town of Monte Carlo form one of the most breathtaking views in the whole Riviera while in one semicircle in front of the house stretches the blue of the Mediterranean.’ ”

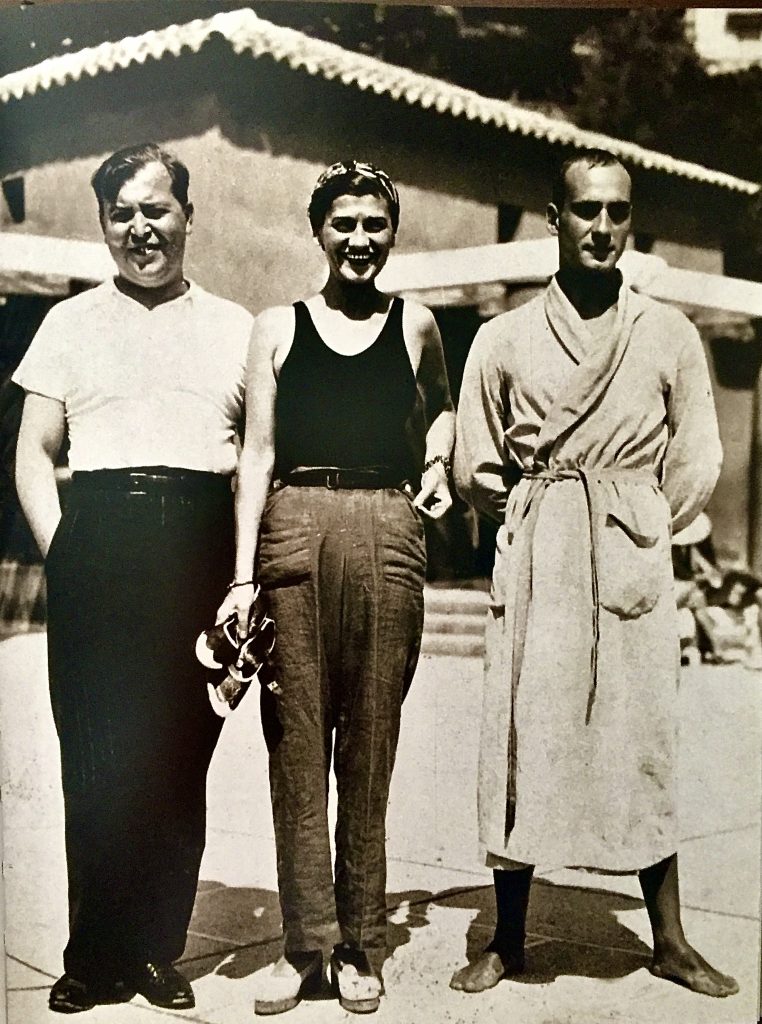

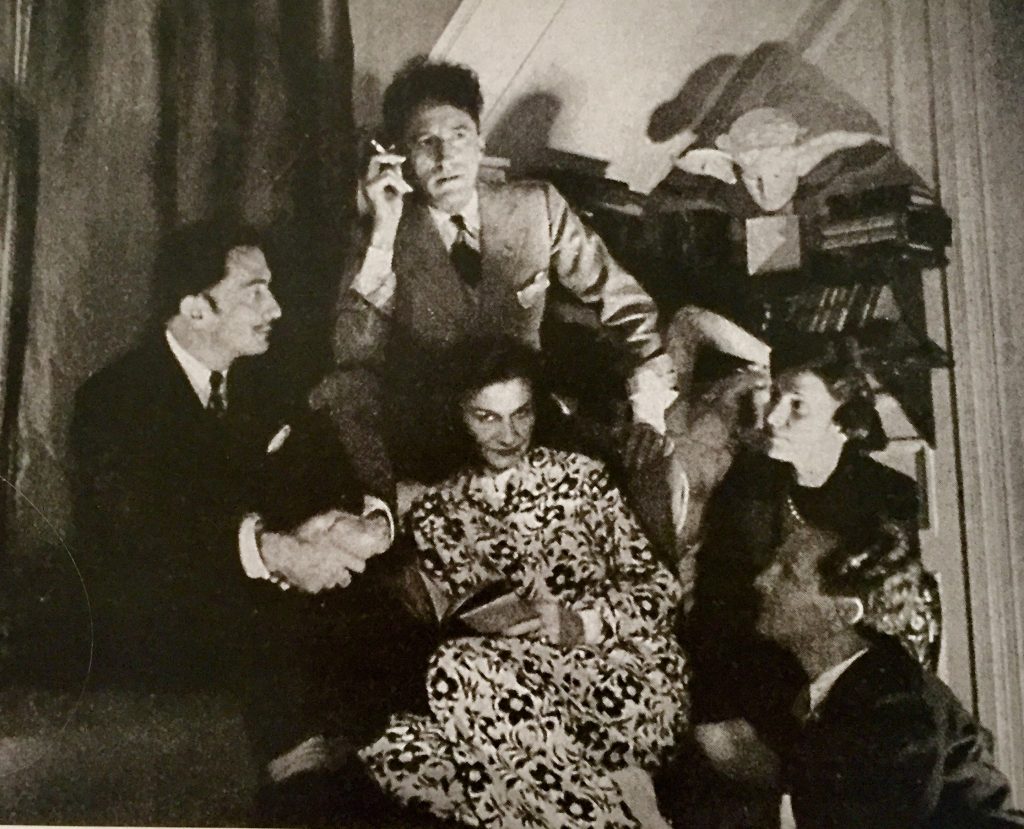

Chanel in Monte Carlo with Christian Béard and Boris Kochno 1932

Chanel’s financial independence had been established prior to the purchase of the property for La Pausa. Other properties she bought in Paris included: 31 rue Cambon in 1918, number 29 in April 1923, number 25 in April 1926 and numbers 27 and 23 in October 1927. Her business acumen never failed her. Morand said: “To be free and independent was one of the finest examples she set for women.”

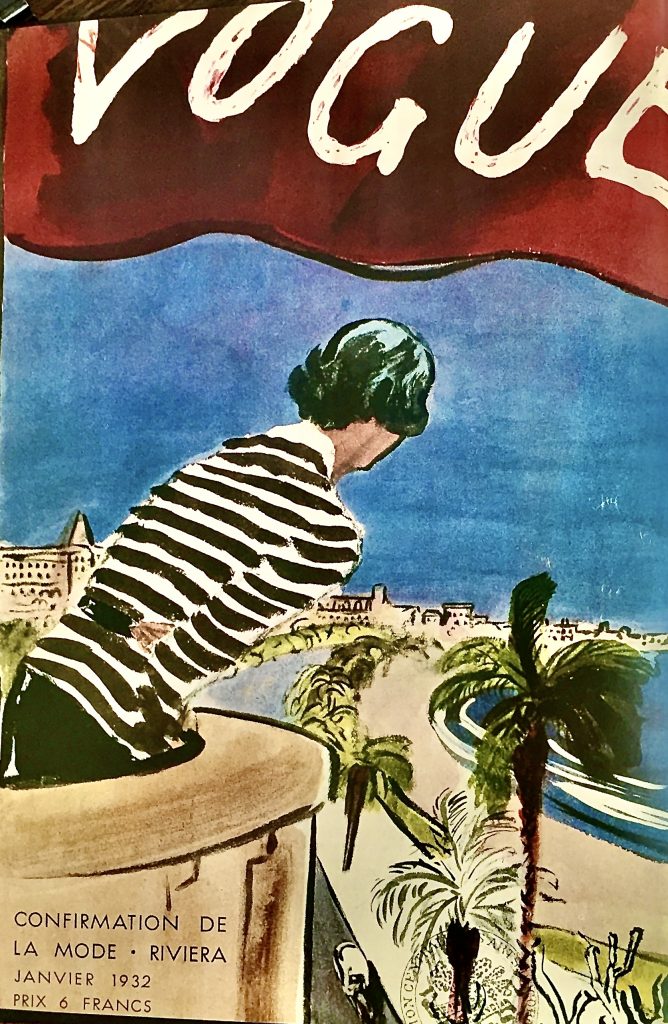

Chanel on the cover of French Vogue January 1932. Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Justine Picardie recounts an amusing quote from Chanel about yachts. Coco said to Claude Delay: “A yacht, was by far the best place to begin a love affair. ‘The first time you’re clumsy, the second time you quarrel a bit, and if it doesn’t go well, the third time you can stop at a port’.”

Chanel: “Work has consumed my life. I have sacrificed everything to it, even love.” As with every other venture she tackled, her heart and soul went into every aspect of the construction of La Pausa and its grounds. Work was very important, as always, but the freedom she would feel at La Pausa also became very important and she was determined to make her villa perfect— simplicity coupled with sophistication, a place to rewind and relax.

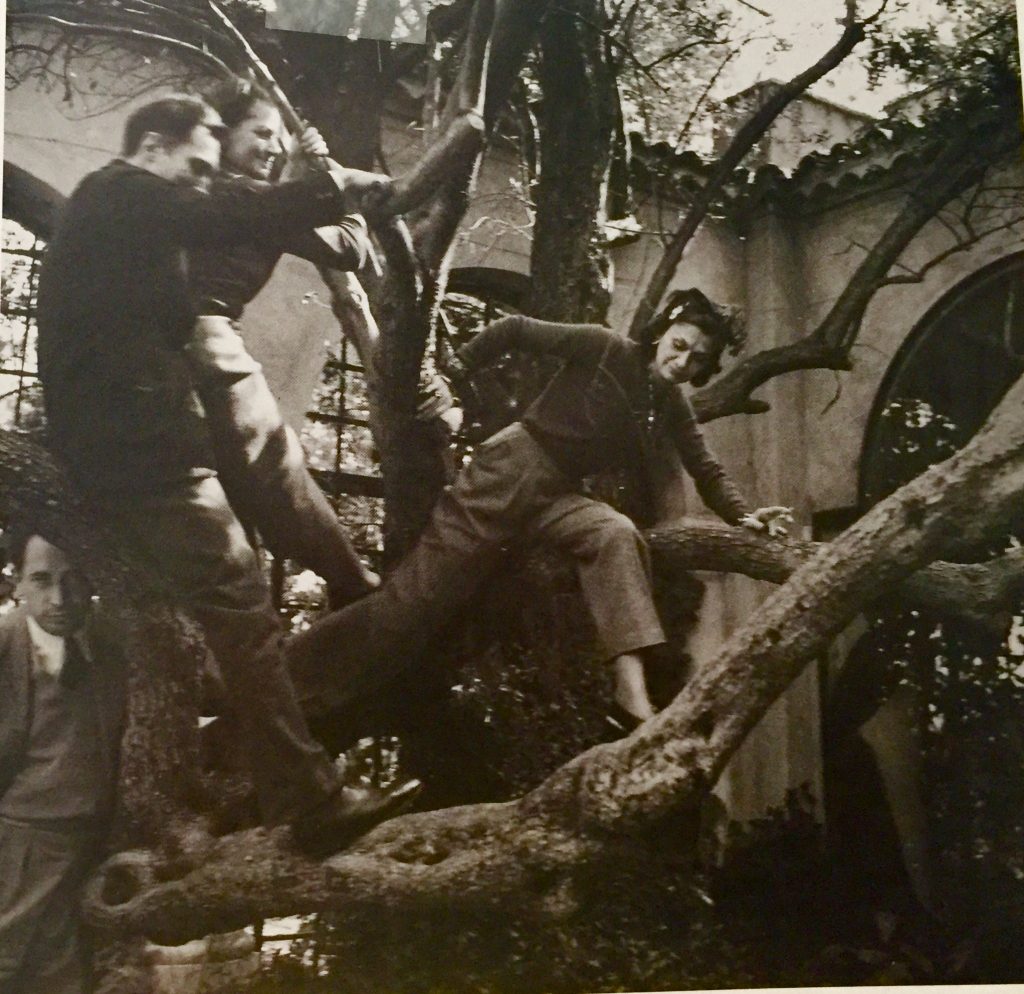

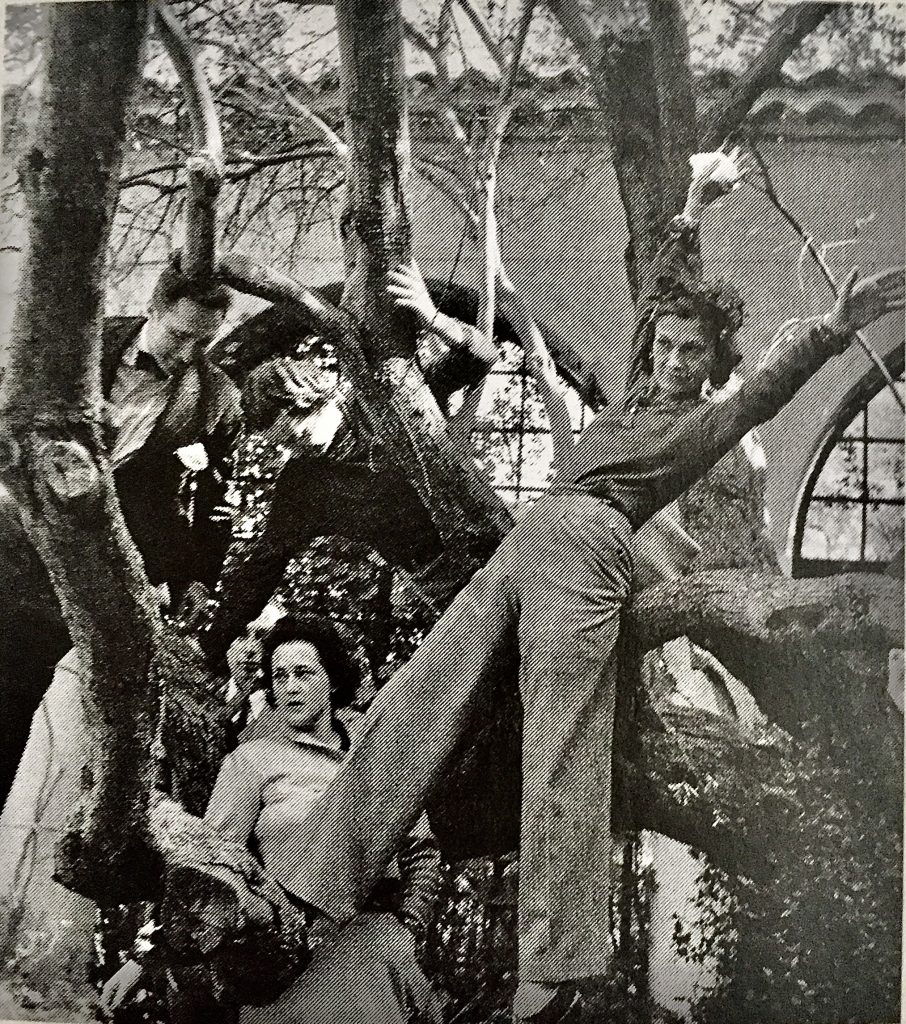

Chanel climbing a tree with friends at La Pausa 1938. Roger Schall 1938

Chanel loved life in the open air. Records from Lochmore 1927 show she was quite good at fishing when with Westminster, at sixteen rode horses bareback and continued riding, becoming more proficient beginning in 1906 at 23 years old with Etienne Balsan and later with Boy Capel, snow skiing in Switzerland, yachting, swimming, golf and although the Americans were credited for making summer the high season, it was Chanel that had made sunbathing popular. Pictures show her climbing a tree at La Pausa in 1938—maybe not a sport but showed great balance! Once telling Paul Morand about sportswear: “I invented the sports dress for myself; not because other women played sports, but because I did. I didn’t go out because I needed to design dresses. I designed dresses precisely because I went out, because I lived, for myself, the life of the century.”

Chanel posing as if she could fly. In the garden of La Pausa. Roger Schall 1938.

She had the property and now Chanel needed an architect. Her friend, Count de Segonzac, suggested Robert Streitz—he had restored the Count’s villa. After the deed was signed, Chanel invited Streitz to a drinks party on board the Flying Cloud that at the time was moored in Cannes. It would be his first major project and he would consider it to be his good luck building.

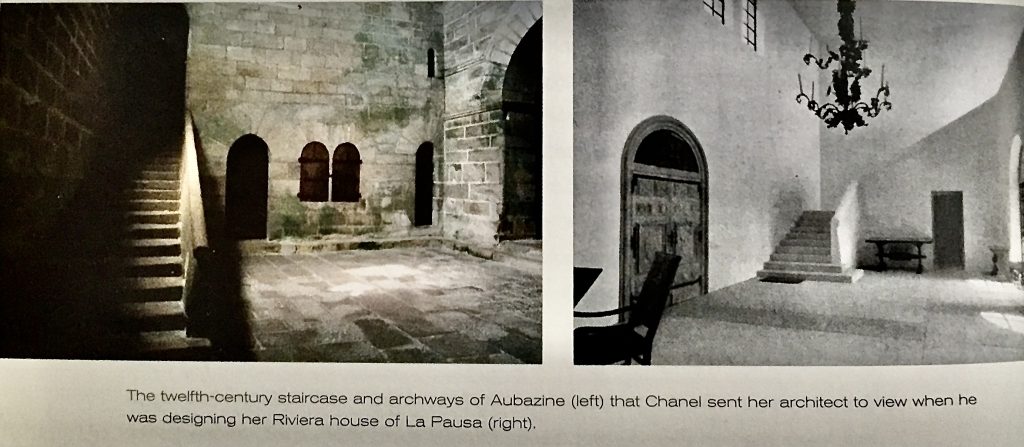

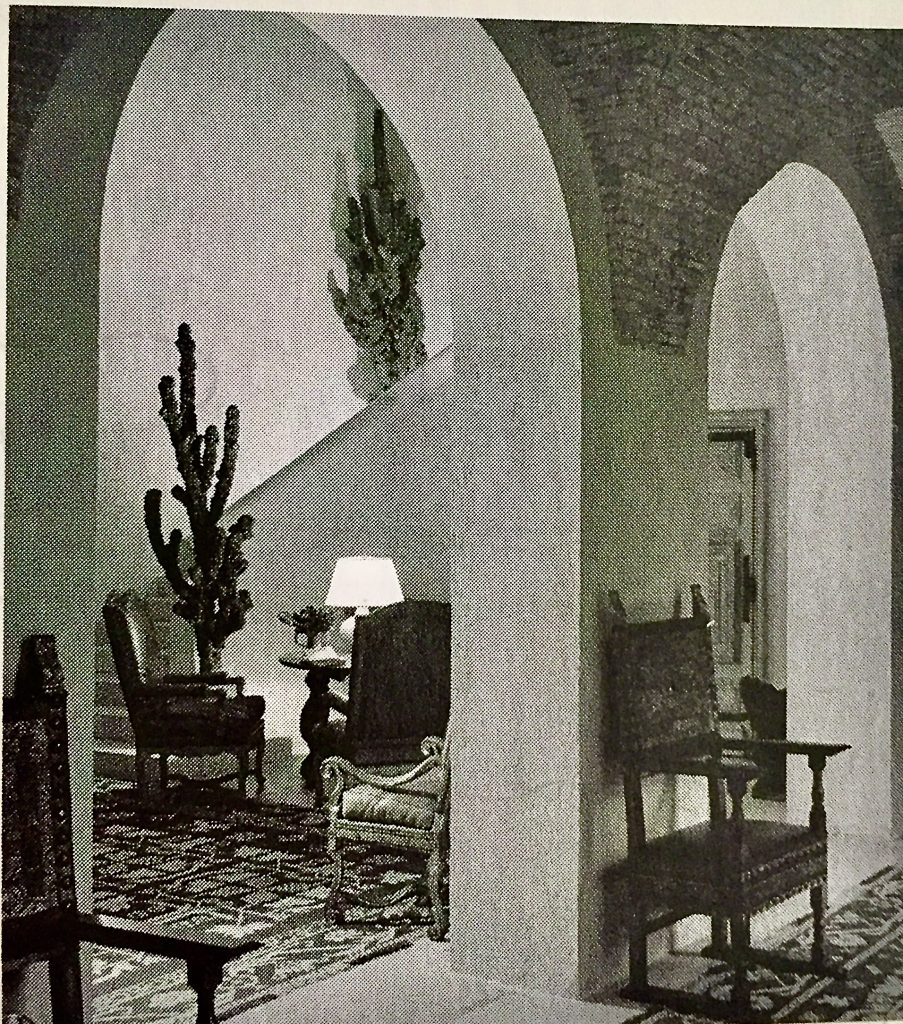

It wasn’t very long before he brought the plans to her. The plans included three wings wrapped around an open courtyard bordered by columns. Aubazine had three sides facing inward onto a courtyard. She accepted his plans right away but telling him that he had to visit the Aubazine abbey and capture its atmosphere and its main features, which he did, thus the staircase in La Pausa mirrors that at Aubazine— where Monks had walked ahead of generations of orphans. Streitz interpreted the cloistered colonnades of Aubazine, vaulted ceilings, and heavy doors. The dramatic white staircase became the centerpiece of La Pausa. Chanel lived at the Aubazine orphanage from age twelve to eighteen.

Chanel making alterations to a model’s dress.

The mission Streitz was given was to build the ideal Mediterranean villa. In a conversation with French journalist Pierre Galante forty years later, he recalled the Duke’s instructions: “I want everything to be built with the best materials and under the best working conditions.” In the Romanesque vaulted brick ceiling of the entry, the lights are decorated with the crown from the Duke’s coat of arms. The major decisions, the important ones, were made by Chanel and she alone, but this detail was one where his influence can be seen. I assume that the Duke did have some influence, as the couple made numerous and regular yachting trips along the Riviera.

Streitz remembers that she could be intimidating and found it best not to linger after a conversation, he didn’t want to hear her say he was a complete idiot as I think he once had. He also recalls that Chanel was very generous. Once when he had to take the bus to Roquebrune because his car had broken down, Chanel gave him one of her cars in the garage that was similar in size to his. It was his to keep.

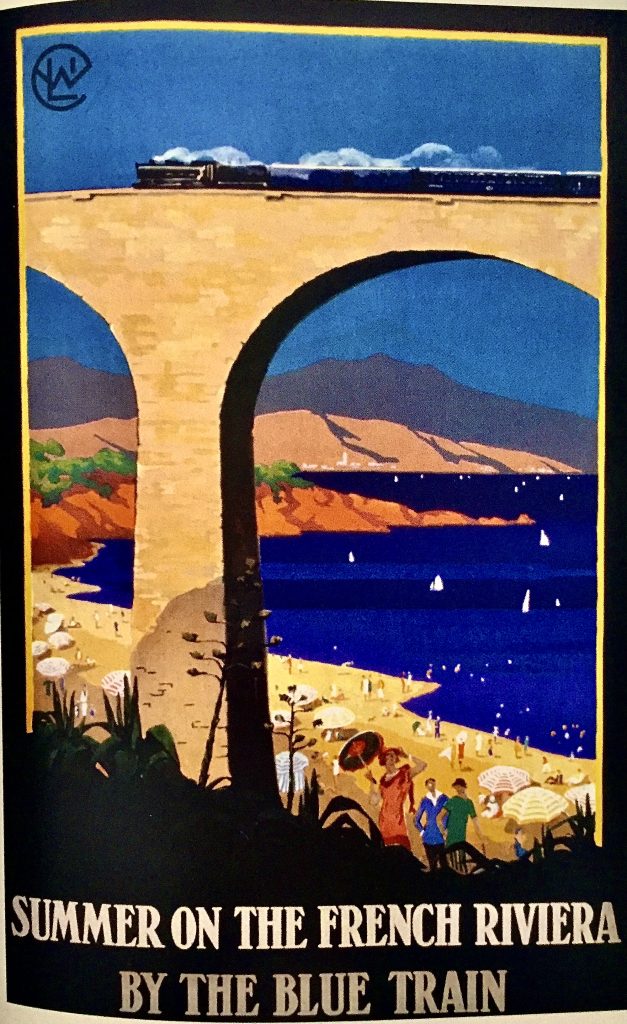

The chief builder was Edgar Maggiore. He too respected Chanel, but at the same time was a bit anxious around her. Once saying to Galante: “Mademoiselle knew what she wanted.” Her instructions to him were that the villa must have the patina of age—20,000 handmade roof tiles made to look old covered the roof and the dark green shutters, that kept out summer’s heat, were weathered to achieve the look of having been there for a very long time. (I remember the shutters on the windows of the first place I stayed in the vieille ville de Menton—they were dark green.) He recalls: “She was always very cheerful when she visited Roquebrune.” It also seems Mademoiselle had a sense of humor when one time she didn’t overreact, but instead, started laughing when she sank to her knees in mud inspecting the vast foundation. Another one of Maggiore’s recollections is the time Mademoiselle didn’t have time to go to La Pausa from rue Cambon. Maggiore sent one of his workmen to Paris so that she could choose the exact color she wanted the facade. At a minimum, Chanel visited the property once a month, taking LeTrain Bleu from Paris to Monaco—on occasion, returning on the same day. It could be that the close attention she paid to the project, was the reason it was completed in less than a year.

Le Train bleu–it was a most pleasant way to travel to the French Riviera!

In his retirement, at Valbonne in the Alpes-Maritime, Streitz recalls: “We never had a contract or any kind of correspondence…For me Mademoiselle’s word was as good gold. Nine months after the completion of La Pausa, every last bill had been paid on the nail.” The cost of the construction was 6 million francs—equally costly was the interior. But, with all of the lavishness, it is noted by several sources, there was a feeling of simplicity and serenity.

Chanel with her dog, Gigot, at La Pausa.

When La Pausa was at last completed, she welcomed the friends, artists, writers, musicians and lovers she most admired and loved. It’s said she was a relaxed hostess—guests stayed for a few days or weeks or months. Indeed, a place for all to relax or unwind surrounded by groves of olive trees, lavender and rosemary. Among those that visited La Pausa, were Jean Cocteau, who considered her “the greatest dressmaker for her era”, Pablo Picasso, Pierre Bonnard, Igor Stravinsky, Salvador Dali, Luchino Visconti and Paul Iribe. Paul Morand was a visitor at La Pausa—his interviews with her in 1946 in Switzerland are found in his book, The Allure of Chanel. Chanel saying to him: “I am the only volcanic crater in the Auvergne that is not extinct.”

Chanel surrounded by friends, Salvador Dali, Jean Cocteau, Madame Dali and M. Samosa.

Salvador Dali, with his wife, Gala, were frequent visitors. Chanel lent him La Pausa for six months in 1938 where he worked on paintings for a show in New York the next year. He was inspired while at La Pausa to paint his still-life, “L’Instant sublime”. It shows a snail, telephone receiver and a drop of water about to fall—very provocative, very Dali.

To Paul Morand Chanel said: “It was artists that taught me rigor.” Chanel was a patron to artists in various fields over the years. Her introduction of Franco Zeffirelli to Brigette and Roger Vadim, launched his career. Chanel networked when at the time networking was not a thing. Vanity Fair June 1931: The headline, “ We nominate for the Hall of Fame”. Going on to say: “…because she combines a shrewd business sense with enormous personal prodigality and a genuine enthusiasm for arts.”

Charles-Roux comments on the atmosphere of the La Pausa:

“While her friends sensed a bit of the convent, Chanel declared that she had advised her architect to visit a monastery where, as a child, ‘she has spent marvelous vacations.’ In truth, she had sent him to Aubazine, to that orphanage whose severe beauty continued, secretly, to haunt her.”

Chanel had her past built into La Pausa.

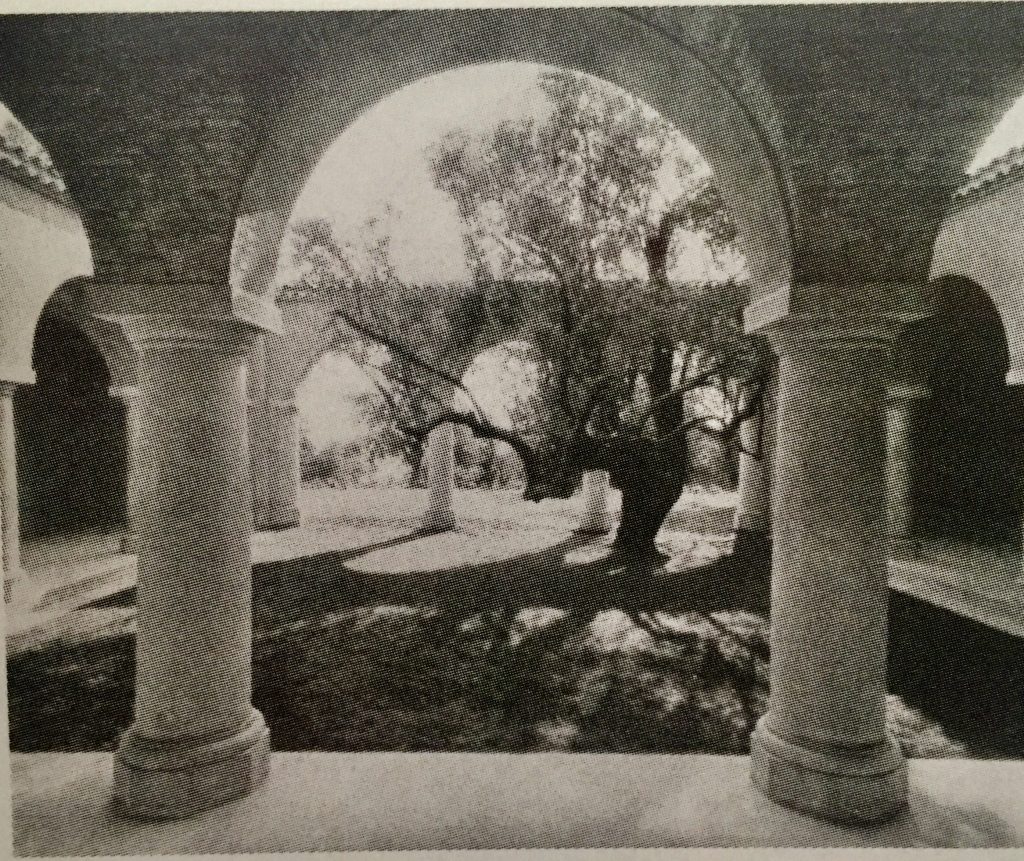

View of the cloistered colonnade.

In the house, white taffeta curtains hung in the dining room that matched the white walls. In the living room and bedrooms were beige silk curtains. Each of the seven en suite guest bedrooms was large and cool, had a separate entrance so guests were not disturbed—these entrances were used by servants to draw a bath or deliver new towels, to take away clothes to be press or cleaned, or shoes were taken away to be shined. Picardie credits the Italian majordomo, Ugo, for the villa being “run with immaculate efficiency.” Chanel and the Duke each had their own suites upstairs—her view, the garden where there were 350 ancient olive trees, daisies, mimosa, and iris.

Interior of the cloistered colonnade–an ancient olive tree in the center.

Chanel’s great-niece, Gabrielle Labrunie, remembers La Pausa: “ ‘I was certain that there were fairies in the garden in Roquebrune. They were in the trees, and there were stars entwined in Auntie Coco’s bed.’ ” Picardie explains exactly what Labrunie recalled: “They were carved in wrought iron to Coco’s design, surrounding the bed in which the Duke was her guest; the emblem of her own domain (and perhaps also a subtle reminder of the stars she walked upon as a child, decorating the mosaic floor at Aubazine)…The surviving pictures of Chanel’s bedroom at La Pausa still show the stars that her great-niece remembers so well.”

“ ‘The house itself is long and Provençal,’ reported Vogue, ‘the grey of its walls melting into the soft tint of the wood of the olive trees.’ The cloisters were built along three sides of the patio, providing shade ‘where one may cooly doze away the hottest hours of the summer afternoons…The motif seems to be an entire absence of knickknacks or unnecessary items. Everything one needs is there—and the most perfect of its kind—but there is nothing superfluous.’ ”

Interior showing heavily carved Provençal furniture.

Charles-Roux’s comments about the garden: “Here Chanel sought the natural above all else, thereby affirming her aversion to fussy and facile effects. It was a house in which to live the life of the times…In the garden, under the century-old olive trees, reigned a single color—lavender blue.” Per Chanel’s request, Maggiore got 20 more ancient olive trees. He found them in Antibes—one of those trees was planted in the center of the courtyard.

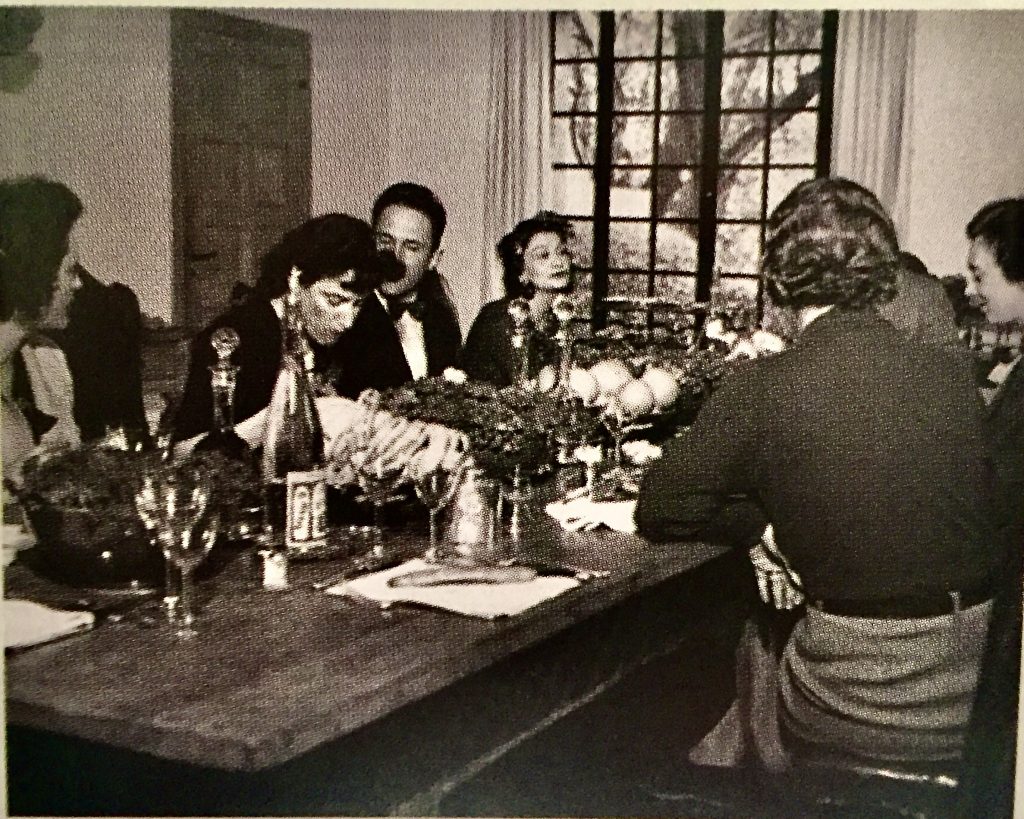

The leisurely days at La Pausa began with guests rising whenever they wished, a thermos of coffee was left at their bedroom door—Chanel slept late. Anne de Courcy says the day really began with lunch—conversation and when plans were made. Dress was informal as were the meals. Lunch was served buffet-style, with food served in antique silver dishes from England on a long table at the end of the dining room. Small cars were available to take those that wanted to go down the 2 kilometers of twisting mountain road to Menton to shop or swim in the sea. Mornings and afternoons were spent swimming, playing tennis or simply lounging. Chanel was an avid reader. I can visualize her reclining on a chaise longue reading—you may, or perhaps not, be surprised the authors she was drawn to. On her shelves at rue Cambon, were authors Homer, Tolstoy, Brontë, Proust, to name but a few. To Paul Morand saying: “Books have been my best friends.”

Chanel was an avid reader all her life.

Yew hedges hid the tennis courts at the top of the garden. A terraced hillside was where you would find changing rooms for the swimming pool and bath, the laundry and staff quarters, the caretaker had a separate apartment. On the property, was a covered terrace that provided shade for dining or perhaps to sit and read or have a chat.

Lunch is served. Chanel with her guest, Jean Hugo.

Bettina Ballard, in a piece for Vogue, described a house party: “ ‘About one o’clock everyone appears in the great hall—mornings don’t exist in the South, and you see no one before. Mademoiselle Chanel is generally the last, and her appearance on the high white balcony above the hall starts the day’s animation… She wears navy jersey slacks with a slip-on sweater and a bright red quilted bolero…Her red canvas espadrilles have thick cork soles—excellent for walking.’ Chanel rarely left the property, according to Ballard, except for her long afternoon rambles over narrow rocky paths’… ‘The comfort of the house is phenomenal.’ ”

Chanel and friends.

Roderick Cameron recalls his encounter(s) with Chanel at La Pausa: “It sits in an old olive orchard on these of a hill above Cap Martin. La Pausa, she called it…it is under Chanel’s aegis that I like to remember the house; large low-ceilinged rooms, sparsely furnished, with handsome pieces of Spanish and Provençal furniture…she was one of the first to start the no-colour habit, only in Chanel’s case the gamut ran in the beiges: quilted Provençal cotton and huge sofas covered, I think, in chamois leather. The garden was equally simple, planted only with lavender and rosemary, and all-round the smoky light filtering through the centuries-old olives. Chanel had a wonderful sense of luxury and great taste. I can’t say I was one of her intimate friends, rather I observed from a distance and listened; indeed this silence was a condition she imposed on most of those around her, induced by the fact that she seldom stopped talking. Our conversation escapes me, but not her presence, which was tomboyish but alluringly feminine. She wore trousers and a sweater and a great deal of jewelry, wide ivory bracelets encrusted with a Maltese cross of rubies, and rows of pearls. I think the secret of Chanel’s great success as a couturier was the fact that she never designed anything that she could not wear herself, and which suited her piquant, boyish charm…an unerring eye for colour and an innate sense of quality.”

Rooftop of La Pausa and its view

This observation of Cameron fits other references people made about her conversations. Chanel once said: “The most courageous act is still to think for yourself. Aloud.” Charles-Roux recalled when: “Chanel stretched out and reading after a harassing day, possibly asleep, or sitting as upright as the letter “I”, struggling to resist fatigue, impatient and eager to plunge into one of those torrential monologues that she passed for conversation.”

Imagine, if you can, being at La Pausa with Chanel in attendance as she is surrounded by her friends and only people she enjoyed, and listen to the fascinating things she would have to say. She was avant-garde in every way. To stroll in the garden, where there were groves of orange trees, slopes of lavender, purple iris, and climbing roses. What would you ask her? Was she wearing pearls and her Maltese cuffs? I wonder.

Twelfth-century staircase and archways at Aubazine, and on the right, staircase and archways at La Pausa.

After Bend’Or’s death in 1953, Chanel sold La Pausa to Emery Reve, a writer, publisher, financier and art collector, and his wife the American model, Wendy Russell. From the obituary of Wendy Reves, in The Telegraph, 16 March 2007:“Set among olive groves and lavender fields high above the Mediterranean, it was an idyllic place, and under the Reveses became a centre of Riviera social life; guests included Greta Garbo, Somerset Maugham, Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, the Duke of Windsor, Aristotle Onassis, and Konrad Adenauer.”

La Pausa is at last back in the hands of the House of Chanel. As the French ambassador to Monaco, Huges Moret, said about the sale by the Reves in 2013, “it was part of French heritage…We have to find a way to keep it in the family.” The House of Chanel announced the acquisition of La Pausa on September 30, 2015. The owners of the House of Chanel, Alain and Gerard Wertheimer, stated: “It is thus an essential testimony to Gabrielle Chanel’s life that has now become part of the heritage of Chanel. After renovations to restore it to its original spirit, La Pausa will take on a new lease of life and radiate the culture and values of Chanel.”

Interior of La Pausa. Roger Schall 1938

Visit the Dallas Museum of Art and come away with a sense of what it must have been like at La Pausa. Wendy Reves occupied the house until her death in 2007—the house was then closed. Reconstructed at the museum, are six rooms, including the staircase, from La Pausa. Works of art and objet d’art from La Pausa are displayed in these rooms—The Wendy and Emery Reves Collection.

Salvador Dali and his wife, Gala, on the staircase at La Pausa. Numa Blanc Fils 1938

La Pausa is just up the “hill” from Menton and Cap Martin, where I have spent many lovely summers, and hope to once again. I wanted to know more about it. This curiosity quickly drew me into the world of Chanel. I can’t say it will ever be open to the public, one can hope, but if ever it is…I will amble along the delightful pathways in the gardens and tour the villa where once Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel lived and spent glorious days on the Côte d’Azur.

À Bientôt

*Jacques Polge, the “nose” at Chanel, inspired by the gardens at La Pausa, created le parfum, “28 La Pausa”, in 2007.

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson

The Allure of Chanel, by Paul Morand, published by Pushkin Press 2017 Translated from the French by Euan Cameron

The Golden Riviera, by Roderick Cameron, published by Editions Limited