By Cheryl Anderson

“No elegance is possible without perfume. It is the unseen, unforgettable accessory of fashion that heralds your arrival and prolongs your departure.”

—Chanel

Parfum Chanel Nº5 was considered the first modern perfume and the first to boldly feature a designer’s name on the bottle. Launched in 1921, it fast became one of the most sought after fragrances — it continues today to be among the most popular perfumes in the world. Once again, at nearly forty, Coco Chanel would leave her mark — with perfume.

Yes, Chanel was a brand, a style, but she also viewed it as a lifestyle. Coco Chanel had long wanted a sophisticated fragrance to go with her brand — she loved scent and wore perfume every day. Often quoting the poet Paul Valéry: “A woman who doesn’t wear perfume has no future.” — saying in an interview in 1968: “Well he was quite right.”

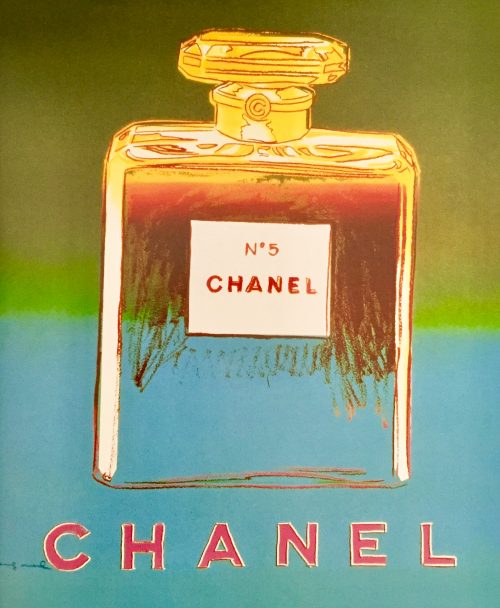

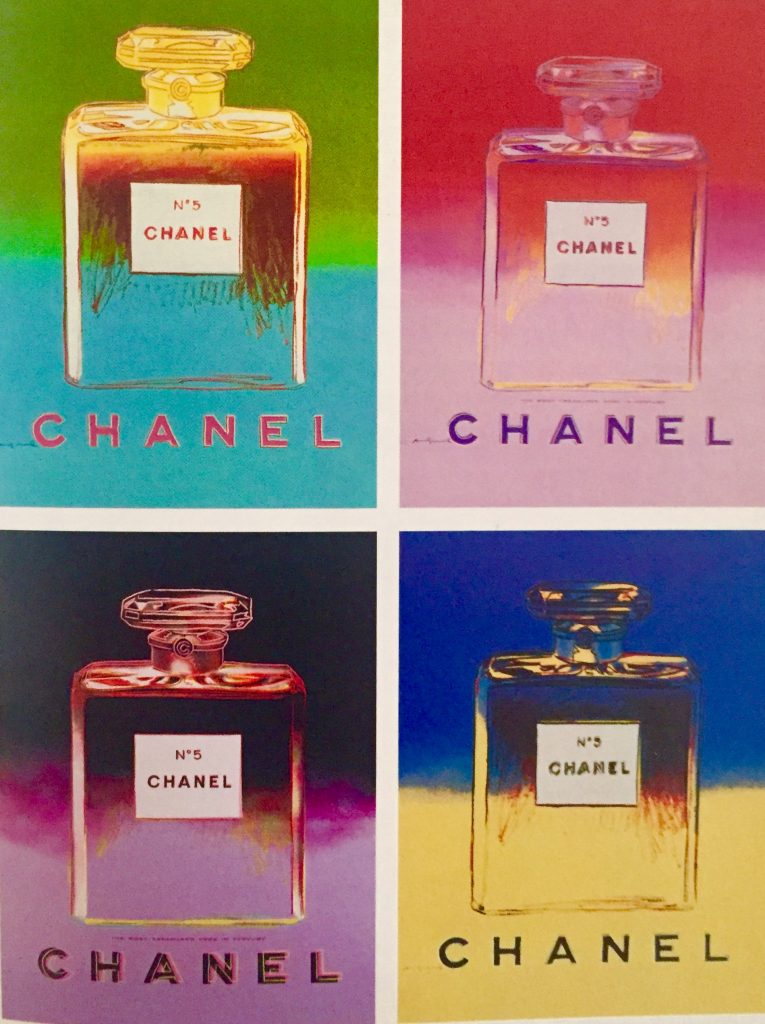

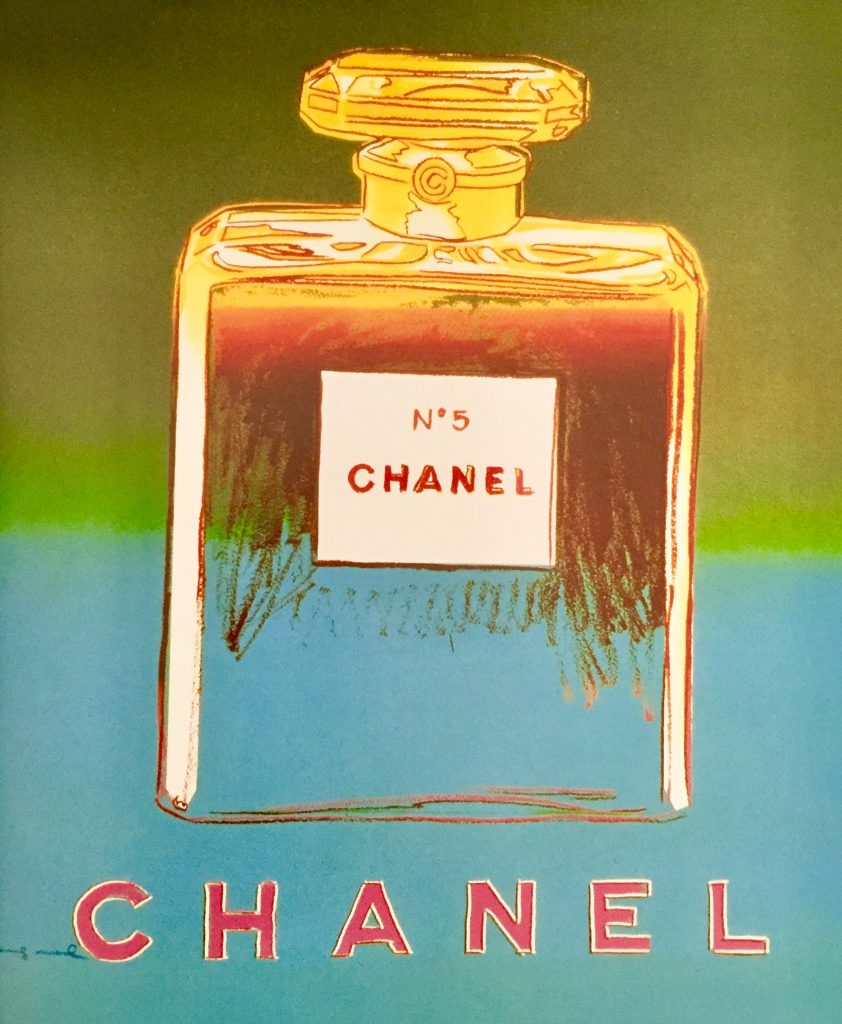

Silkscreen of the Chanel Nº5 bottle by Andy Warhol.

Chanel was fastidiously clean and had a keen sense of smell. Telling Paul Morand: “It smelt of filth downstairs; there was no surface upon which you could use a duster or apply any polish…”. It was as though she could smell dirt. She liked how the courtesans, (cocottes), she had met during her time at the family estate of Ètienne Balsan, Royallieu, always smelled clean — comparing them to the rich ladies that wore perfume with a heavy musky smell and body odor.

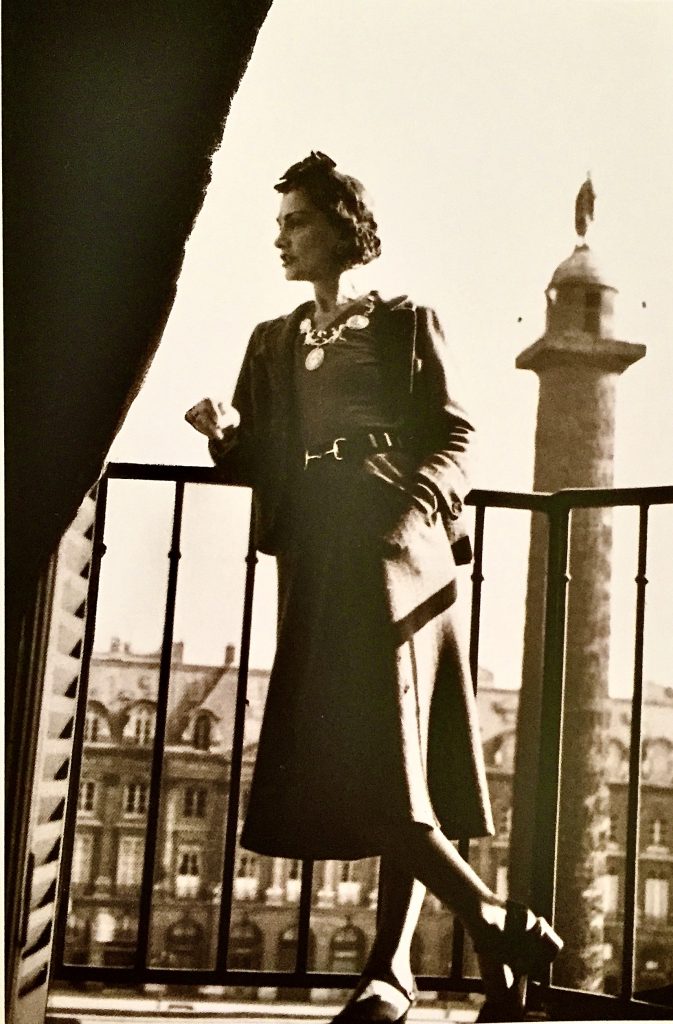

Chanel appearing in an ad for the first time she was featured promoting her perfume (1937) — photo taken by François Kollar in her suite at the Ritz.

Remaining with her whole life, were memories from the convent and the smell of soap and freshly scrubbed skin. Coco recalled childhood memories to Claude Delay: “…of the smell of lye soap at her aunts’ house, of their linen cupboard fragrant with herbs; of the polished floors and furniture, in a place where everything was clean.” Further telling him: “The sense of smell is the only one that is still instinctive. It lives on nostalgia, the subconscious.”

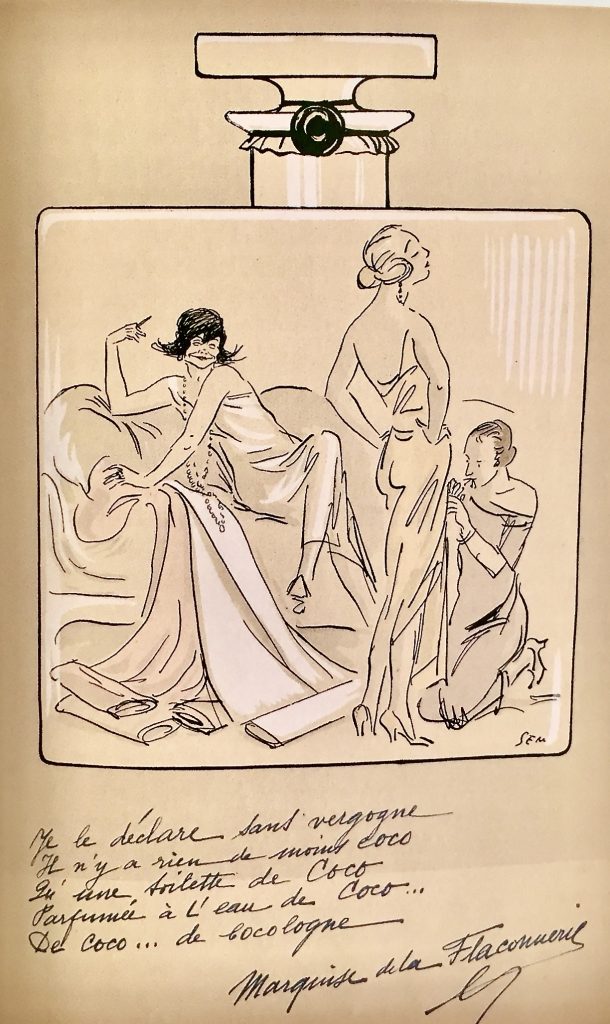

Caricature of Chanel (1921) by “Sem” — George Goursa, famous French caricaturist during the Belle Èpoque.

Chanel met Dimitri Pavlovich, her new lover, in Biarritz — her affair with Igor Stravinsky was over. A story I especially like is one where she had a conversation with Paul Morand about her meeting Dimitri, asking him: “I have just bought a blue Rolls (Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud), let’s go to Monte Carlo.” They left for the Riviera — Dimitri played golf during the morning and Chanel stayed in bed late. In the afternoon, the two of them met for lunch, toured the surrounding villages and churches in the countryside, ate out for dinner, and gambled at the Casino. I can envision them on the winding road along the coast and in the villages that I am so familiar.

Dimitri introduced Coco to Ernest Beaux, chemist, and a master parfumeur. He had been the master perfumer at A. Raillet and Company since 1898. The company was the official perfumer of the Russian court.

Ernest Beaux, the Russian chemist that made it all happen.

His is a very interesting story, serving in France during the First World War (1914-1917), awarded the Croix de Guerre and Légion d’Honneur for his courage and later commissioned by the British as a counter-intelligence officer, receiving the British Military Cross, again for his courage. Beaux finally made his way to the south of France and established his laboratory and factory in Grasse. He was approached by Chanel to make her perfume.

Chanel wanted a perfume that presented the aura of femininity, explaining to Beaux: “Create a scent that would make its wearer smell like a woman, and not like a rose.” Before Chanel Nº5, the elite socialites wore perfumes with a single flower scent — pure essences of gardenia, rose, heliotrope, and jasmine. They were delicate perfumes and because of the way they were formulated, wore off.

Chanel on the balcony of her Ritz apartment (1935).

How was it Beaux created such a unique perfume with so many natural florals? After many tries, he had the scent, but it was heavy and remained at the bottom of the bottle. It needed to be fresher. His genius led him to add the right aldehydes — they not only intensified the natural potion, but lightened it up and it lasted longer than other perfumes.

He explained to Chanel with over 80 florals mixed together, with a jasmine note, it would be very expensive. Chanel asked what was the most expensive floral? When he told her that jasmine was the most expensive ingredient and nothing else was more expensive, she said: “Well then! Add more. I want the most expensive perfume in the world.” (To this day, jasmine, from the valley of Siagne, above Grasse, comes from the original regions in gardens reserved just for Chanel.)

“La Marquise de la Flaconnerie” (1923) caricature by “Sem”.

Anne de Courcy: “Chanel, however, believed that women — by which she meant her society clients—were now more liberated and ready to embrace perfumes that were sophisticated and sensual, which would serve as a counterpoint to the almost spartan chic of her clothes.” The deeper heavier perfumes, now relegated to the demimondaines, were based on musk and civet — they were long-lasting, but overwhelming.

Beaux presented her with his creations, numbered 1-5 and 20-24. There are numerous legends why she decided on Nº5. Ernest asked her what it should be called? A popular, and very convincing account, in her words: “I am presenting my dress collection on the 5th of May, the fifth month of the year; let’s leave the name Nº5.” Boy Capel had educated her on the precepts of theosophy and she would know the significance of the number five, the fifth element — the quinta essentia of the alchemist. Then there are the five-sided stars in the paved mosaics in the corridor of the abbey at Aubazine where she lived for six years as a child and Leo, her birth sign, is the fifth sign of the zodiac.

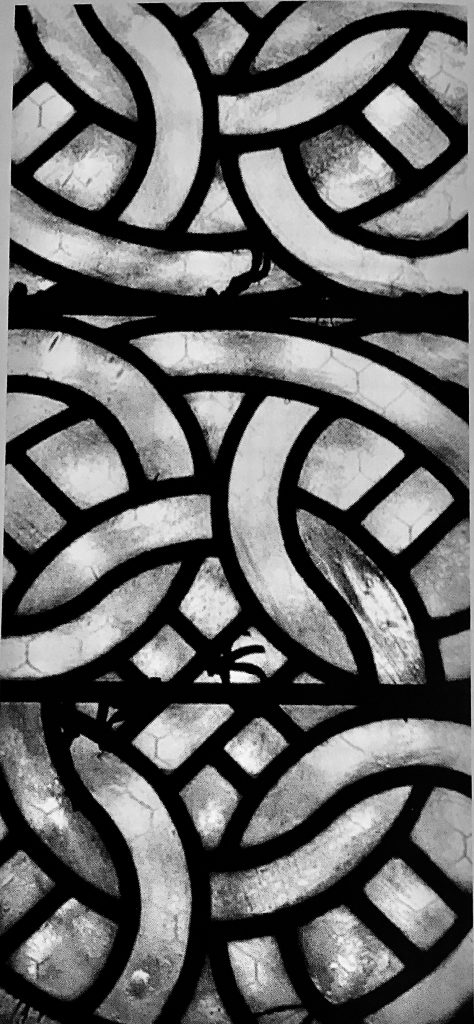

Window pane in the Cistercian abbey in Aubazine.

Her friend and confident, Claude Delay, recounted Coco’s choosing the Nº5, from a discussion he had with her towards the end of her life. He puts the story of why the name in a lovely manner: “She took refuge on the Côte d’Azur where, breathing in essences and the fields of May roses, she invented the perfume — Nº5 — which was to obsess the world. The name was a chance, not premeditated. She called it that because it was the fifth bottle and five is a pretty number.” Chanel had lost the love of her life, Boy Capel — he died in an automobile accident on December 22, 1919. In a way, she was bottling her future along with her past memories.

Another time, when talking with Delay about perfume, Chanel told him: “Women wear the perfumes they’re given as presents. You ought to wear your own. If I leave a jacket behind somewhere, they know it’s mine. When I was young, the first thing I’d have done if I had any money was buy some perfume. I’d been given Floris’s Sweet Peas — I thought it was lovely, country girl that I was. Then I realized it didn’t suit me.”

Chanel Nº5 — in miniature on a button.

In the end, Chanel got what she had envisioned, stating: “It was what I was waiting for. A perfume like nothing else. A woman’s perfume, with the scent of a woman.” What Beaux had created was a contemporary perfume that as she described it: “a bouquet of abstract flowers”. Author, Justine Picardie, goes further: “And she (Chanel) also added another element to Beaux’s expert chemistry: an understanding the alchemy of desire.”

It goes without saying, that Chanel was a marketing genius. She and Beaux, with a few friends, dined in the most fashionable restaurant in Cannes the night after she had chosen Nº5. She sprayed the ladies as they passed her table — done in such a surreptitious manner that they were made to ask, what was the delicious scent? She told Delay: “You’ve got to be able to lead them by the nose.” She sprayed her boutiques in Deauville, Biarritz, and Paris before the production had begun. Her best clients and socially prominent friends were given small bottles and told they were in on her little secret — an elite club belonging to the rich. She had created a status symbol.

Chanel Nº5 became synonymous with beauty.

The fitting rooms at the salon on rue Cambon were given a spray. Before she entered the building, the entrance received a spray — Chanel Nº5 made the air even more rarified at 31, rue Cambon.

Chanel approached Théophile Bader, owner of Galeries Lafayette, hoping he would sell her perfume in his department stores in order to reach a broader market — at the time it was only sold in Chanel boutiques and to select clients. Bader knew that he would need greater quantities, more than Beaux could provide, so he introduced her to Pierre Wertheimer, owner of Les Parfumeries Bourjois, one of the largest cosmetic and fragrance companies. Their first meeting took place at the Deauville racetrack. She entered a business agreement with him whereas Wertheimer’s company would fully finance production, distribution, and marketing for her beauty products setting up Les Parfums Chanel in 1924. Her perfume sales soared, opened up her brand to the masses and made her very wealthy.

Chanel came to regret the partnership having settled for only 10% of the company — resenting that the business bore her name and she got so little. However, she made millions giving her economic independence for the rest of her life. The legal battle that ensued went on for years. The Wertheimers have kept Chanel in private ownership, unlike other couturiers and beauty brands that have been absorbed by world conglomerates.

When the American GIs arrived in Paris, they lined up in front of her boutique, holding up five fingers and were given a free bottle of Chanel Nº5 for their wife or sweetheart back home. It was a promise she had made — she put a sign in the window that the scent was free for GIs. It was a gesture that helped, in some small measure, play in her favor as her life became complicated after the war. She had a German lover, Hans Günther von Dincklage, and lived at the Ritz during the war. (Ever the pragmatist, Chanel moved to Switzerland in 1945. There she lived with von Dincklage part of the time for several years.)

GIs lined up outside to get a free bottle of Chanel Nº5 (1945) they only had to hold up five fingers and a bottle was theirs.

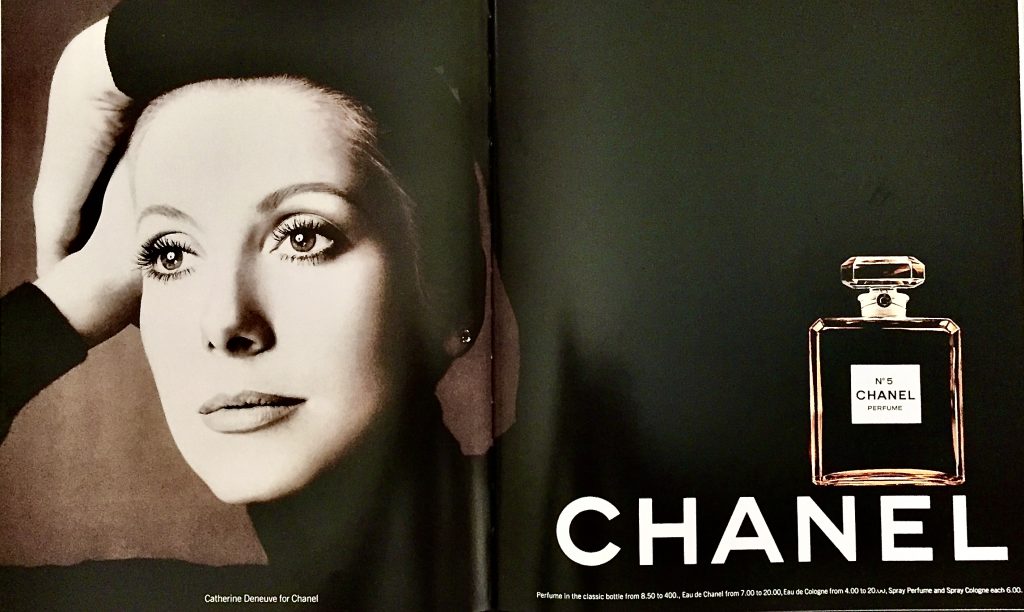

The first time Chanel ever appeared in a Chanel Nº5 ad was in Harper’s Bazaar (1937) — the photo was taken by François Kollar in her suite at the Ritz. We can all recall the many beautiful ladies that have appeared in Chanel Nº5 ads; Catherine Deneuve (heralded as the new face of Chanel in the revitalization effort of the company in the 1970s), Suzy Parker, Ali McGraw, Carole Bouquet, former Bond girl, Nicole Kidman, Gisele and, never to forget, Marilyn Monroe in 1954.

Catherine Deneuve for Chanel Nº5 (1972). Photo by Richard Avedon.

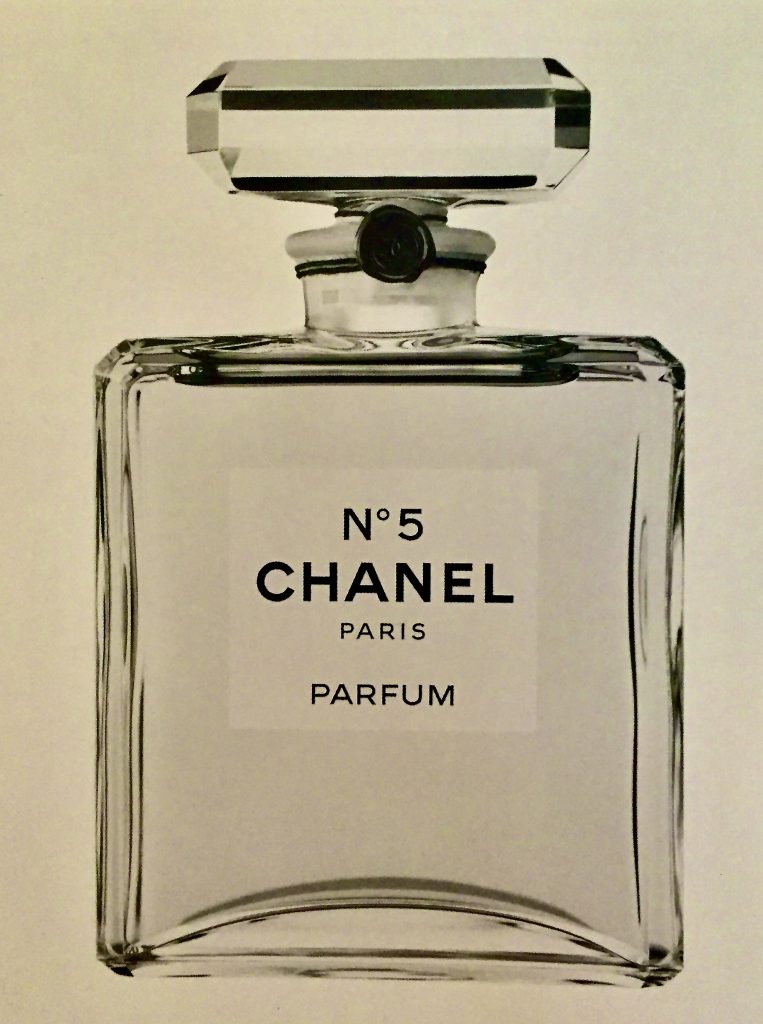

The design of the flacon has its stories, but make no mistake it was Mademoiselle Chanel, herself, that made the final decision on the minimalistic design of the bottle. Some believe Dimitri designed the original flacon — naturally, I can’t say for certain whether or not that is true. The bottle has simple Art Deco lines. Her biographer, Charles Roux, describes it thusly: “a spare, minimal bottle — a flagon as clean as a cube — that stood in stark contrast to the frippery then favored by perfumers.” Where did her ideas come from? Toiletry cases of her lovers gave her ideas of how it should look. The bottle is strong and square in contrast to the new modern, light, and delicate fragrance within. The final design, indeed, went well with and evoked the same spirit as the chic simplicity of her clothing line.

Such a pretty understated flacon — Chanel’s chic simplicity is carried out in its design.

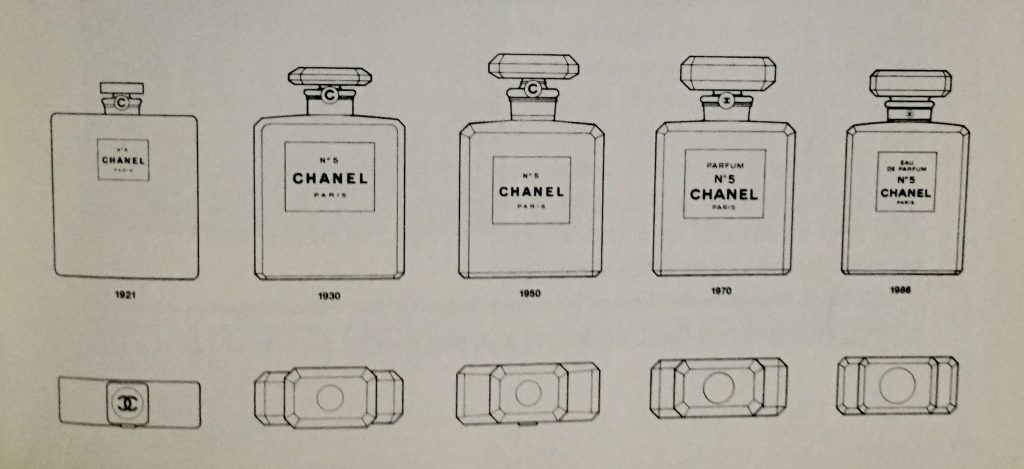

The first one in 1921 resembled a whiskey bottle or flask, but when the redesign was made to the bottle in 1924 it had square, faceted corners. This design has remained, more or less, the same since then. The thin glass and rounded shoulders of the original bottle design had to be changed because it would not survive being shipped — important to the new company, Les Parfum Chanel, who would be shipping a lot.

A postcard from my collection.

However, the stopper has been modified a number of times. The original stopper was a small glass plug and then in 1924, the same year the bottle was modified, the new stopper was introduced — it became a brand signature. In the 1950s, the larger octagonal bevel cut stopper had a thicker silhouette only to become even more prominent in the 1970s. Making the proportions more in tune with the scale of the bottle, in 1986 it was changed again. To appeal to even an even broader market, the pocket flacon was introduced in 1934.

Chanel Nº5 bottles changed through the years.

Notice, on the top of the stopper of the first bottles produced, the interlocking double Cs — Chanel designed the logo in 1925. I found three possibilities of their meaning. Boy Capel, the love of her life, could be one of the Cs, together, but facing apart, or are they from the Château de Crémat in Nice owned by her friend, socialite Irene Bretz? The double Cs were the symbol of the vineyard and decorated the property’s doorways and stained glass windows. Both make perfect sense and those that believe one or the other are fully convinced it is the true reason. Or, could perhaps the panes in the stained glass windows in the Cistercian abbey of Aubazine have influenced the creation of the double Cs? The mystery of the interlocking Cs joins the many mysteries that surround Coco Chanel—mysteries that will never be fully explained or a definitive answer given as to what was her intent.

The mysterious interlocking Cs on a button…

The absolute truth behind many of the personal stories Chanel related to friends and interviewers may never be known, for very often they changed — famously saying: “My life didn’t please me, so I created my life”. Question marks will always remain — why she named her first perfume Nº5, the meaning of the double Cs, and did Dimitri actually design the flacon? To my mind, these legends and mysteries only make her more fascinating and a joy for me to research.

Mademoiselle Chanel famously said: “A woman should have ropes and ropes of pearls.” That story is for next time. Coco Chanel — Her Pearls.

À bientôt

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson