By Cheryl Anderson

“My jewels represent an idea, first and foremost! I wanted to cover women with constellations.”

—Chanel

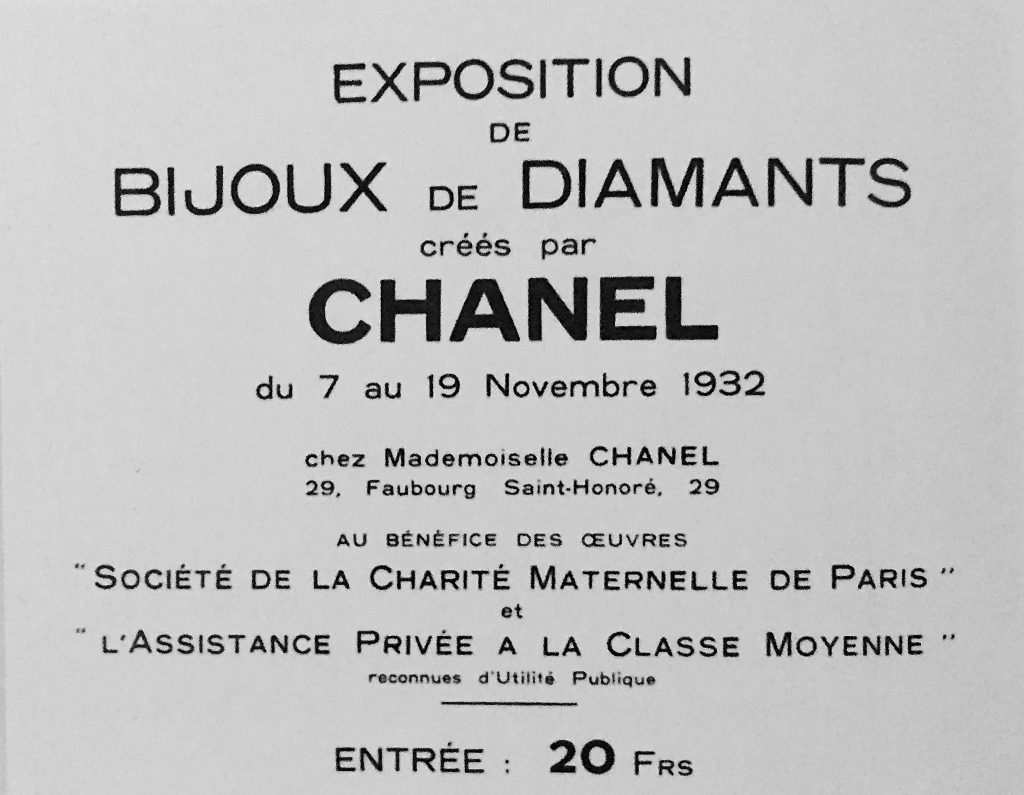

On a grey day in Paris, 1 November, 1932, All Saint’s Day, one could purchase a ticket for 20 francs and view rooms filled with Coco Chanel’s creations of diamond jewelry—celestial gems. Sparkling diamonds juxtaposed against the backdrop of the homeless on the street and unemployment. For a moment, at least, visitors could escape the dark mood of the Depression that had begun at the end of 1929—perhaps their mood was brightened just a bit. Princes, Princesses, and Ambassadors were among approximately 30,000 visitors. As they strolled through the rooms, all were amazed and fascinated by what they were seeing.

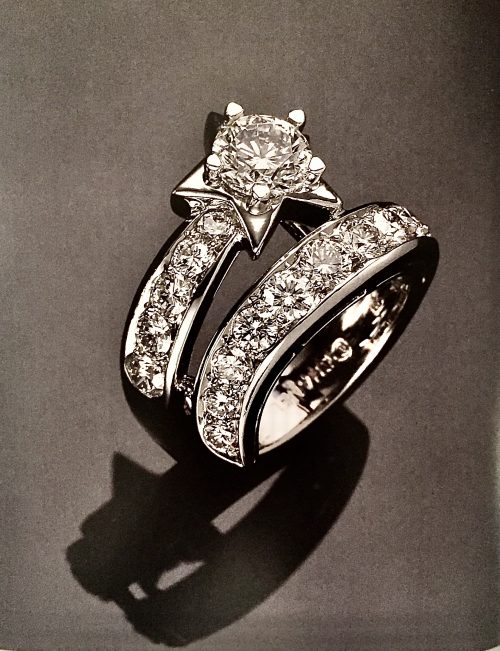

‘Fontaine’ necklace. Shown is a reissue from the 1932 original in platinum.

Danièle Bott states: “Coco Chanel, the queen of audacity, who until then had exalted the pure forms of classicism à la française, allowed herself a moment of contrition. A woman of contrasts who had previously designed only costume jewelry, ‘because it was devoid of arrogance in an era of overly easy luxury’ and criticized in no uncertain terms the ostentatious glitter of real jewelry, Mademoiselle now exhibited the most sumptuous, exuberant, and phantasmagorical collections of diamonds ever, for all of Paris to see.”

Chanel declared in the exposition catalogue: “priceless diamonds were the only way forward ‘during a period of financial crisis when an instinctive desire for authenticity is reawakened in every domain.’” Her signature in the brochure read, “Gabri elleChanel”. Janet Flanner comments in The New Yorker, “in her long, dramatic career as a dressmaker, she has never been more elleChanel, or herself, than this curious exhibition of diamonds just opened in the interests of charity (and diamond merchants) in her sumptuous private hôtel in the Faubourg St-Honoré.”

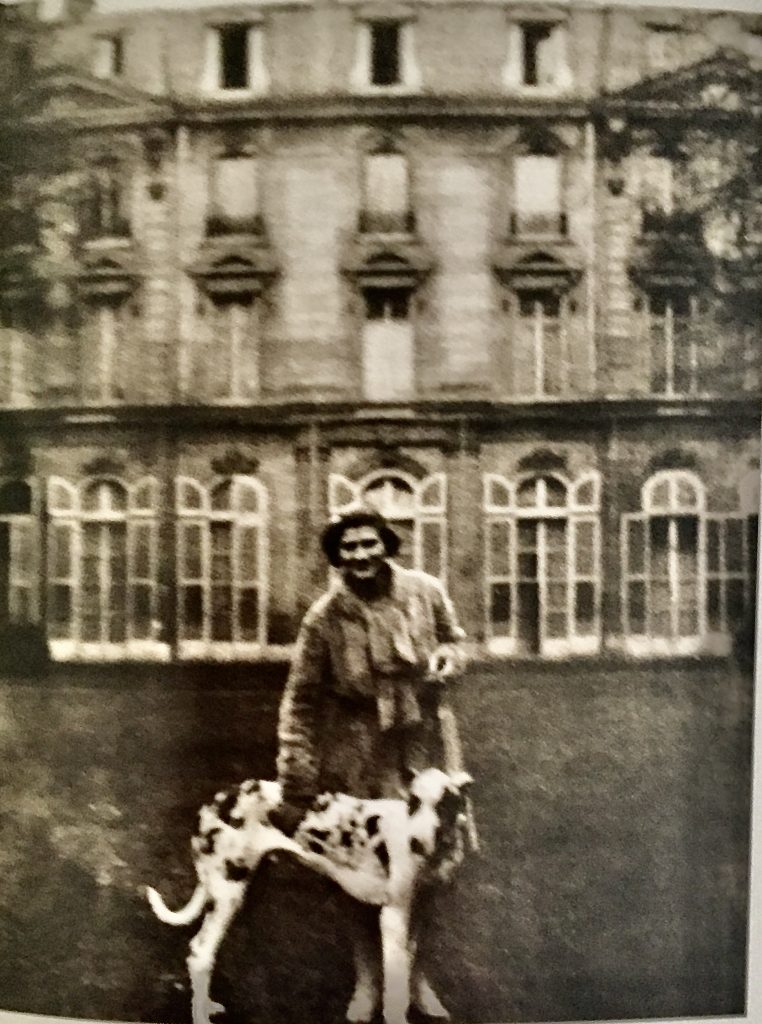

Coco with her dog, Gigot, in front of the hôtel particulier, 29 Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris.

The sparkling event, Chanel loved things that sparkled, was the Exposition Bijoux de Diaments, créés par Coco Chanel—it lasted for a fortnight. The location of the exposition was the hôtel particulier, 29 Faubourg Saint-Honoré, in the private apartment of Mademoiselle Chanel—her new residence. Being on the ground floor suite, she could conveniently enjoy the formal gardens right out her door. This move was from the Ritz to one of the most prestigious streets in Paris—she would later return to the Ritz. Although, she still entertained at her apartment on rue Cambon and retreated there when she felt the need to get-away.

Invitation to the remarkable display of diaments.

Imagine, if you can, walking into Chanel’s private rooms— it was her home where she chose to present her first fine jewelry collection. The brilliance of the diamonds added sparkle—93 million francs worth of sparkle. (Justine Picardie says the amount of the borrowed brilliants was 50 million francs.) Vitrine cabinets housed the jewelry, displayed on wax mannequins, so lifelike there was an eerie feel about them—were the eyelashes or hair real or fake? Picardie describes them as being: “locked away like Sleeping Beauties, although their eyes were open, unblinking in the dazzle of diamonds reflected against a backdrop of mirrors.”

The apartment was as much a part of the exhibition as was the jewelry. Bott describes the rooms thusly: “…with its high ceilings and golden wood paneling, evocative of a luxurious past.” Rooms were filled with most of her Coromandel screens, antique furniture, mirrors, a grand piano. Anne de Courcy says there was a Regency sofa covered in orange velvet and the overall palette were the colours cream, beige, black and gold. There were rose-quartz chandeliers hanging from the ceilings—indeed a dramatic setting, yet the overall decorations evoked simplicity.

Boy Capel first introduced Coromandel screens to her, and they became part of her life. She once said: “I’ve loved Chinese screens since I was eighteen years old…I nearly fainted with joy when, entering a Chinese shop, I saw a Coromandel for the first time…Screens were the first things I bought.” The folding, black-lacquered screens were decorated with images of birds, flowers and some were inlaid with ivory, tortoise-shell or mother-of-pearl. Functional, as they could hide a door or create private and intimate corners of a large room.

“Plush carpet everywhere”, she (Chanel) recalled to Paul Morand, “colorado claro in color, with silky tints, like good cigars, woven to my specifications, and brown velvet curtains with good braiding that looked like coronets girdled in yellow silk.” Pairs of private policemen were stationed at each doorway keeping close watch—they were visibly armed with revolvers.

How this new venture began: The gemstones were on loan from the Union of Diamond Merchants. They approached Chanel asking her to publicize their jewels during the devastating economic slump. It’s said that two days after the opening of the exposition DeBeer stock rose 20 points on the London Exchange.

Chanel had made costume jewelry à la mode, how could she now promote diamonds? Her decision was not made lightly. Bott: “Her work was one of her main reasons for living, and in that regard, she trusted no one but herself, only her own ideas, her instinct as a woman of fashion, of acumen, of business.” Thus, she accepted the request from the International Diamond Guild.

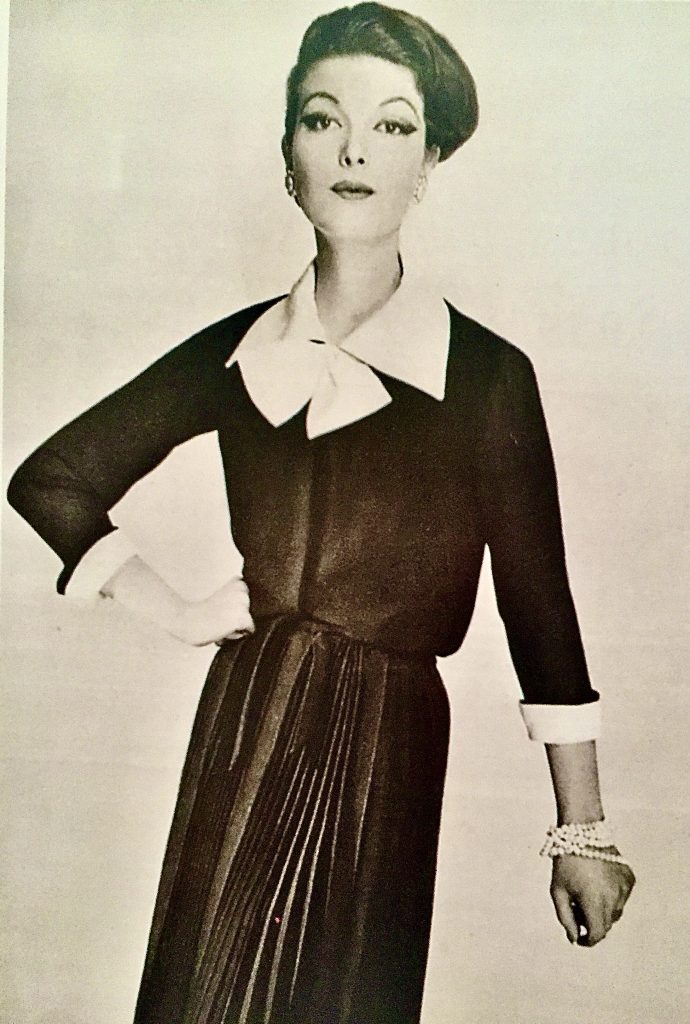

A white piqué bow on a Chanel little black chemise dress as seen in L’Art la Mode, 1958. Chanel also made turned-up cuffs (in white) a la mode. Photo Georges Saad.

For the DeBeers collection, she turned to her Basque lover, Paul Iribe, (born Iribarnegaray). His talent was as a designer in the fields of textiles, advertising, graphics, and stage design, and was a celebrated caricaturist. Both he and Chanel were forty-nine at the time. Anne de Courcy: “Theirs was a stormy, passionate relationship. Given to outbreaks of temper, shouting matches…Iribe was one of an intellectual bohemian circle rife with emotional entanglements.” She had tired of the idle life of the rich with Westminster.

Paul Iribe

Janet Wallach: “She and Iribe worked as a team, bathed in harmony one moment and in volcanic rage the next…She leaned on him in business.” They met in 1931, he was designing for Cartier and was married. That didn’t stop him from living with Coco within months of their meeting. The exact date of the beginning of their affair is not known, according to Justine Picardie. This was a happy time for Chanel who evidently believed that finally, in the person of Iribe, she had met the man of her life. Chanel was drawn to his intelligence and refinement, stating, “the most complicated man” she had ever known. Both loved luxury and had exquisite taste. These things were not present in the relationship with Westminster.

Iribe with Cecile B. DeMille (1923). Iribe created the sets for the movie, The Ten Commandments

They lived together for three years dividing their time between her apartment on Faubourg Saint-Honoré and at La Pausa, her retreat near Monaco in Roquebrune-Cap Martin. It was the center of her summer life and where whenever she could steal-away. Friends thought they would marry, they had known each other for four years. But, that was not to be. In the late summer of 1935, Chanel saw him collapse on the tennis court. Doctors were unable to save him. Janet Wallach: “Once again the sinking sense of isolation surrounded her. There was nothing to do but work.”

Iribe convinced her to move from fake to the real thing, thus they collaborated to design jewelry that could be broken down into two or four different pieces with unseen clever clips and ingenious mechanics, becoming something new—the practical side of their designs.

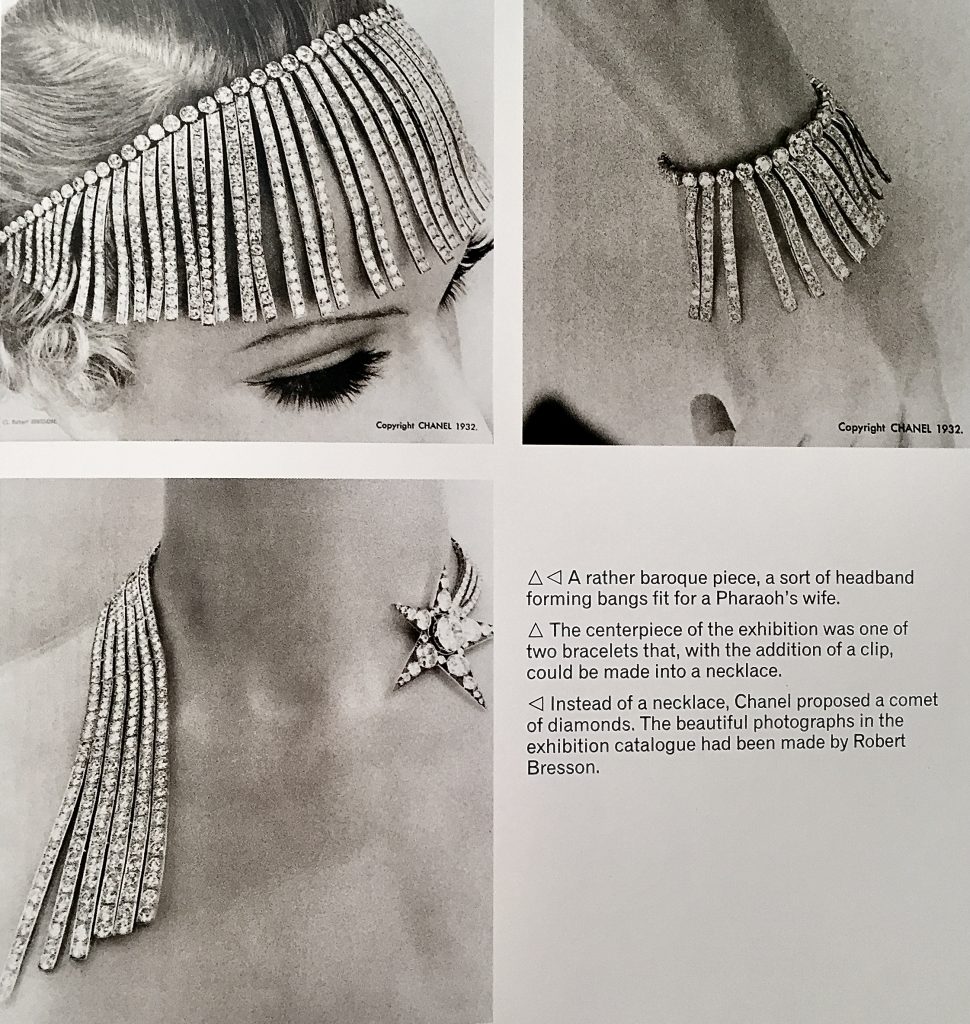

‘Franges’ bracelet. |

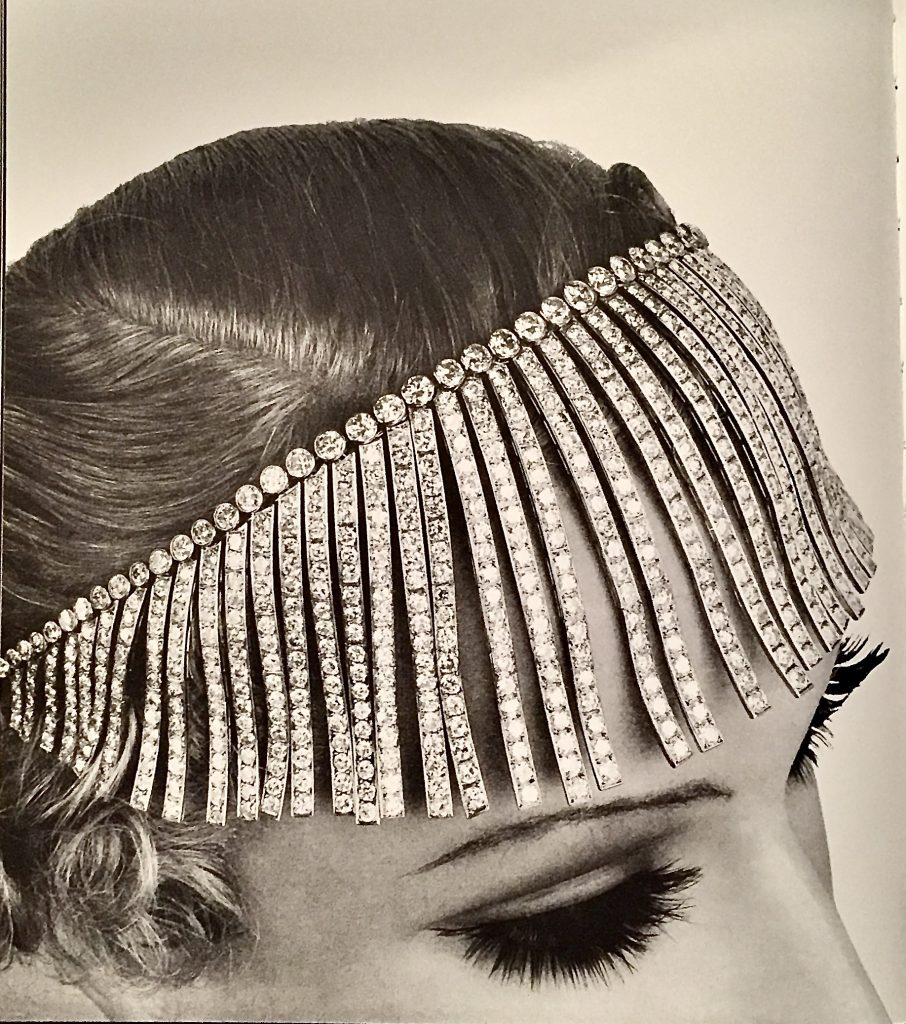

‘Franges’ necklace worn as a tiara–looking like diamond bangs. |

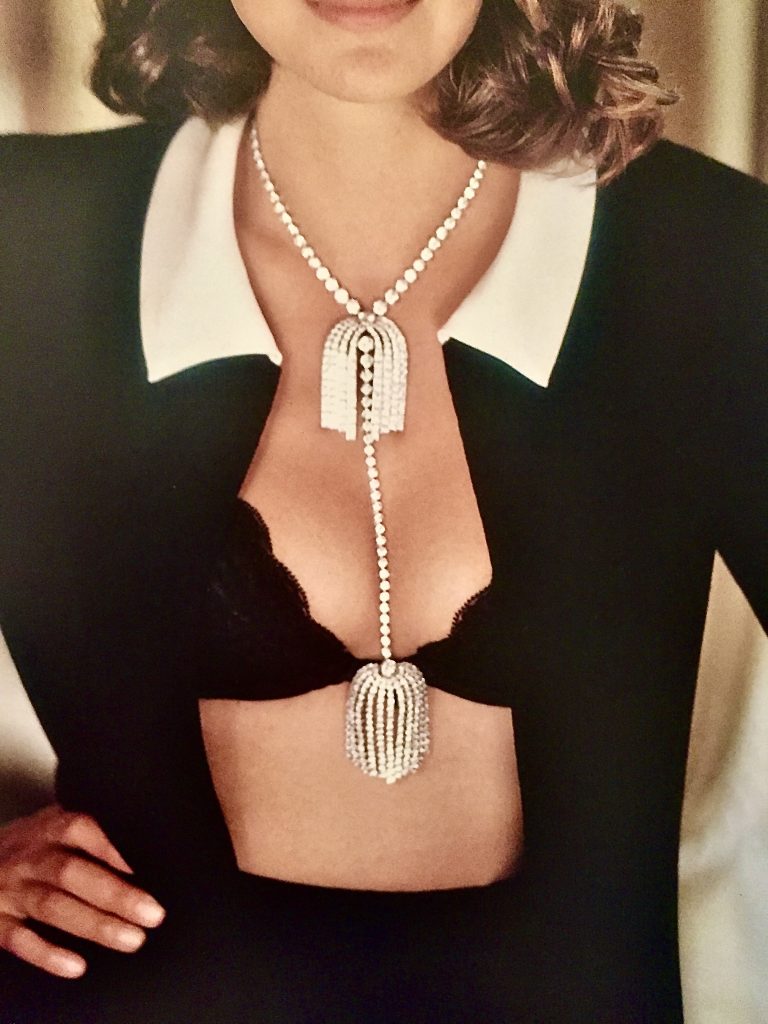

Chanel’s inspiration for her diamond jewelry designs came from the constellations—inspired by the heavens. Picardie states: “…if the exhibition was only temporary, it was also suggestive of the permanence of the constellations…her apparently natural instinct for providing fantastical illusion with a glass of verisimilitude.” Her inspiration took her to create jewelry of stars in all sizes, galaxies, comets, crescent moons, as well as ribbons, bows, fringes and feathers—they became stunning necklaces, diadems, brooches and headpieces. Women could now wear sparkling constellations, comets, cascades of stars, and crescent moons.

‘Nœud’ bow necklace. Bows were a common accent to her clothing designs as well.

A very Chanel detail often applied to a simple little black dress by other designers through the decades. Wildly copied.

Picardie lets us in on the secret that Chanel: “kept close to her heart: that the diamond stars were mirror images of the mosaics on the floor of the orphanage at Aubazine.” The author muses: “ear-drops into brooches; the stars into garters.”

‘Étoille’ brooch.

In Janet Wallach’s words: “His (Iribe’s) delicate displays of bows, knots, and ribbons and his cosmic clusters of crescents, comets, stars and sun-rays drew enormous attention. He created a bracelet made of diamond fringe and a brooch in the form of a foot-long, flexible feather. He cleverly shaped pieces to close without clasps, and, adding another element of surprise, enabled them to be dismantled and converted to other forms; tiaras turned into bracelets, brooches emerged from earrings and necklaces.”

Original pieces with descriptions.

The brooch could become a hairpiece, a necklace could transform into a tiara or four bracelets together became a cuff. Larger pieces broke down into daywear. The headpiece can be worn as a necklace or the bracelets, with a clip, becomes a necklace or a brooch looks pretty on a beret or hat. I read that it was Chanel that proposed the ‘Comete’ necklace—it has been reissued since 1932.

‘Comète’ necklace. |

As the ‘Comète’ necklace looks cascading around ones neck. Appears there’s a vapour trail over her right shoulder. As the ‘Comète’ necklace looks cascading around ones neck. Appears there’s a vapour trail over her right shoulder. |

Coco Chanel: “The point of jewelry is not to make a woman look rich but to adorn her—not the same thing.”—we are familiar with this quote. She did feel this way, of course, and had a line of costume jewelry, but the temptation to help design such opulent diamond jewelry was a challenge she welcomed. The collection Chanel and Iribe created for DeBeers was elegant simplicity emoting Art Deco design. She claimed her intention was not to compete with other jewelers, but in her words to, “give a new lease of life to a very French artform.”

Danièle Bott suggests that: “Mademoiselle wanted her creations to embrace women and mould to their movements; just like her clothes, they had to be flexible, mobile and versatile.” Chanel once stated that: “Jewelry is not unchanging. Life transforms it and makes it bend to its requirements.”

The exposition, bijoux de diaments, was clearly one of the most audacious decisions Coco Chanel had made. Why diamonds, stating: “I chose diamonds because they hold the greatest value within the smallest volume.”

‘Étoille’ ring.

Her career up to this point had been full of such forward thinking decisions, specifically, because she was unafraid to take risks—decisions that ultimately rocked the worlds of jewelry and fashion—making her very wealthy. This time, it was mounting an exposition of millions of francs worth of diamond jewelry. Who else but Chanel!

À bientôt et Joyeuse Saint-Valentin!

*January 10, 2021—fifty years ago on that day, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel passed away in her suite at the Hôtel Ritz, Paris.

*May, 2021—Parfum Chanel Nº 5 will be 100 years old.

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson

www.examplethis.com