April 16, 2016

BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

Only nine years old and full of awe, Carlotta Maher learned her first hieroglyphics by viewing Egyptian artifacts at the Metropolitan Museum on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. This curiosity blossomed into a love of all things Egyptian, a passion which took her thousands of miles from New York, and her eventual home, Chicago, on numerous archaeological digs across the Middle East.

We visited Carlotta and husband David Maher recently in their airy new apartment overlooking Lake Michigan. Carlotta looked beautiful in a necklace of onyx, quartz, carnelian, and gold (containing molecules perhaps from the time of the pharaohs). Around her shoulders was a plum-colored scarf featuring hieroglyphs she can easily translate. Seeing Maher adorned in these regal Egyptian accessories, one’s mind wanders to Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra, but in truth, she exudes the elf-like enchantment of another superstar of the same time: Audrey Hepburn (also sharing Hepburn’s renowned passion for life).

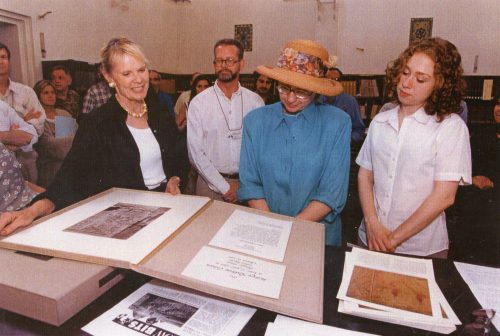

The reason for our visit? Carlotta is now celebrating her 50th year at the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. During her decades with the Institute, coming up on almost twenty years ago in 1997, she was named the first recipient of the James Henry Breasted medallion for extraordinary service. Extraordinary service is an apt description: over the years, the Institute has sent Carlotta far afield, first with an archaeological team South of Baghdad, where, under the burning sun, she cleaned clay tablets filled with cuneiform. On an expedition to Cayonu, Turkey, close to the headwaters of the Tigris, she looked for signs of ancient human blood on prehistoric stone weapons. At Luxor, she translated hieroglyphs on New Kingdom monuments. Each adventure combined her love of antiquity and her passion for science.

“As an only child growing up in New York, I loved my times in the Egyptian wing at the Met. Every weekend, I crossed Central Park and took in the visual impact of the hieroglyphs. My school was very progressive and we spent the entire fourth grade year studying Egypt – what a gift. Before that, I went to the Museum of Natural History, where I showed curators stones I had found in Central Park, and they would tell me what they were. I loved mica because it glittered. That must have led to my fascination with gemstones.”

Her father was a physicist and editor of Popular Science magazine, her mother a crusading newspaper reporter, who covered the Sacco and Vanzetti trial and coal miners’ strikes. They encouraged Carlotta’s fascination with exploration and science.

“As a freshman at Radcliffe, my advisor told me, ‘Girls can’t do science,’ and I said back, in a polite way, ‘Oh, yes they can!’ Ours was the first class of Harvard men and Radcliffe women taking classes together. Before, professors had to teach the same class twice. Women were grudgingly accepted, but once you made good grades, all was well.”

Carlotta married Harvard student David Maher while at Radcliffe and came to Chicago when he accepted a job as a lawyer at Kirkand and Ellis. They had two children, Julia and Philip, and Carlotta worked part time at Children’s Hospital. In 1966, She and another Kirkland wife, Jan Jentes, saw an ad placed by the Oriental Institute requesting volunteers. They both signed up immediately.

“I became interested in the field at every level, from the chemistry of the rock, to the plants, to art history, and the culture behind it all. I began taking graduate courses in 1967 in Egyptology and I am still taking classes today.

“If I am tired of doing one thing when I am at the Institute as a docent, I just look around. All docents have their own expertise, but we have to know about the other areas as well. When you think we offer 5,000 years of history of Egypt, Iran, Turkey, Israel, Jordan, Nubia, Palestinian territories, Lebanon, and more recently Afghanistan, and we have had exhibitions to Iraq, Syria, and Saudi Arabia, one is always learning.

“In the beginning, volunteers at the Oriental Institute could either be guides or gift shop workers. Now they have so many choices, including scanning rare materials into our integrated database and writing tools for teaching in our galleries. Our classes, offered also online, are fantastic.”

Her first Oriental Institute assignment was to work on a team led by Mac Gibson at Nippur, south of Baghdad in Iraq.

“I was there for four seasons before the Iran-Iraq war shut the project down. It was very primitive: no electricity, the sounds you heard were buzzing flies and the ‘scrape, scrape, scrape’ as workers cleared tablets and other objects, and the food mainly bread with tomato sauce. But I loved it! Nippur was the religious center of the Sumerian world in Mesopotamia, where they worshiped Enlil, the god they credited for creating the universe. I remember looking at a pot that was found and thinking that this was used by a woman 2,300 years ago to make food for her family. There are so many times that signs of people who lived thousands of years ago grab your heart.”

When exploration was shut down in Iraq and Iran in 1986, Carlotta was asked to go to Chicago House, an outpost of the Oriental Institute in Luxor, Egypt.

“It is in a very rural and friendly area, between the pyramids of Karnak and Luxor, on an embankment overlooking the Nile. I would go for two months in the fall and David would come for visits. I was in charge of a three-day fundraiser where our guests from all around the world came and we would visit ancient sites not usually open to the public, such as the great rock quarries south of Luxor. We were famous for our tours on donkeys. One year, the donkeys didn’t show up but we managed to get a long bus!

“On ordinary days, we would all be up by 5:30, have a simple breakfast, and after the car arrived to take the Egyptologists and artists to the west bank of the Nile, I was in charge of taking care of whomever walked in the door.”

Carlotta remembers current presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton’s visit with her daughter, Chelsea, years ago in Luxor, Egypt: “I was in charge of Hillary and Chelsea’s visit in 1999. There were men in black crawling all over the property and snipers in our upstairs bedrooms.”

Carlotta was often the chief fundraiser for Chicago House.

“At one point, we had run out of money and our director, Lanny Bell, and I went to Cairo to beg for money from the companies based there. American Express told us to come back next week. When we walked into the Cairo Marriott, built around the large palace where Queen Eugenie had stayed when she opened the Suez Canal, we were looking for a small meeting room with a few guests. Instead, we saw a gigantic ballroom with a huge, newly built model of the Temple at Luxor and hundreds of guests assembled. Chicago House is held in high regard around the world.”

Carlotta describe the lasting impact that the Oriental Institute’s founder, James Henry Breasted, who like Carlotta, was fascinated by scientific exploration.

“He was so gifted, prescient, charismatic, and, like Cleopatra, had an amazing speaking voice. Bible study was his first interest and he then supported himself as a young professor giving public lectures. Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. read his book Ancient Times to her son each night before bed. Soon, her husband had donated the funds to build the Oriental Institute.

“Unlike other archaeologists of his time, Breasted was not just interested in carting off antiquities for the British Museum or the Louvre – although he did bring back treasures for the Institute, the Art Institute, and the Field Museum – he felt archeologists should be interested in everything: seeds, chemistry, culture – all sorts of analysis. He would be so pleased in all the progress in the carbon dating of today.”

Carlotta feels that much of the world’s never-ending passion for things Egyptian relates to the magic of the individuals portrayed in statues and on sarcophagi. One statue at the Oriental Institute of King Tutankhamun has a dedication to the Mahers at its base.

“We will always be fascinated by Cleopatra and her exploits with Caesar and Mark Anthony. Like Alexander the Great, she died young, sometime in her thirties. Both the Greeks and the Romans wrote of her gift for language. The sound of her voice was very extraordinary.

“King Tutankhamun came to the throne at age nine and lived to be only 19. However, there is much we can learn from hieroglyphs about his exploits. We are still unsure about his parents. It has been discovered that he died not of a blow to the head, as originally thought, but from a broken leg that became infected.

“There is much world excitement today because the Egyptian Antiquities Minister has announced that radar scans have produced almost 90 percent proof that there are signs of organic material in a hidden chamber off the tomb of King Tutankhamun. There is a feeling among many that it is the long-lost tomb of Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, who moved the capitol to Amarna. Egyptologists from around the world will come together to study the scans at the end of April. I would love to be there!”

Carlotta also hopes to return soon to Chicago House.

“I have found that Egyptology is more than a study; it is a passion. My colleagues with PhDs in this field are so deeply involved that they consider their work more of a vocation than a career.

“There has been so much damage in Egypt, both ancient and modern. A perfect record is our goal. Our volumes, both print and digital, will serve when the walls are gone. Others saw the need for recording, but Napoleon’s scientists could not read hieroglyphs and Champollion, a French founding figure of Egyptology, was too early for photography. Chicago House uses photographers, artists, and Egyptologists to record and translate.”

For Carlotta, the mystery of Egypt never ends.

“I would love one day to study more of the unsolved mysteries around the Book of the Dead, which contained spells and incantations, monsters and snakes. The pharaohs were supposed to have this in their tombs, on papyrus or on the walls, so that they could navigate in their boats after sunset through many ordeals to reach the field of reeds, where afterlife was to be even easier than one can imagine.”

With the many mysteries Carlotta has uncovered throughout her lifetime, we have no doubt she will unravel this one, too, with ease.