By Judy Carmack Bross

“With only a few moments to go before Lot 242 bidding went live, multiple thoughts were still racing through the collectors’ minds: How many others around the world had actually connected all the dots? how did it get here? this can’t possibly be what we think it is, can it?”— Carl D’Silva in the Prologue to Lost Danish Treasure on the rare watercolor treasure he discovered at a Chicago auction house, inspiring him to write this book.

Carl with Chieftain watercolor.

In Lost Danish Treasure — published by ORO Editions and being released globally in bookstores on August 20th — award-winning Chicago architect, Carl J. D’Silva, who has helped deliver large-scale projects around the world, creates not only a book that is a work of sleek graphic design thanks to his architectural training, but also reveals an intriguing mystery about a seemingly-lost work of high design set amidst a wealth of research. For the first time, the complete story is told of Finn Juhl’s powerful Chieftain Chair of 1949, and how a priceless watercolor of Danish Modern’s most iconic design was re-discovered.

“The resurgence of mid-century modern over the last 20 years had spawned a new appreciation for Danish design, which had faded from the global eye during the latter part of the 20th century,” D’Silva writes. “The Chieftain Chair is one of the most iconic designs of Danish modern. While some furniture designs are celebrated more for their subtleties and details, the Chieftain’s appeal comes from its eye-catching form and distinctive design.” The user is immediately drawn to its comfort, as well as the warmth of its wood and beauty of the leather.

One surprising twist uncovered during research for the book is that the first Chieftain Chair ever made currently resides in a storage floor at the Art Institute of Chicago, and not in Finn Juhl’s house in Copenhagen, as previously thought. The first chair was gifted to the museum in 1971 by one of Chicago’s most celebrated patrons of the arts, Muriel Kallis Steinberg Newman, who bought it in New York in 1950. The 2018 Georg Jensen: Scandinavian Design for Living exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago featured this chair among its silver pieces, as that store was the first to retail the new Danish Modern style in 1948 and had sold its first Chieftain Chair to Muriel. Unfortunately for researchers of today, the original vegetable-tanned leather upholstery had been replaced with a more modern pre-distressed reddish leather just before donation to the museum.

Believing the story of the rediscovered watercolor would appeal to a wider audience than just design enthusiasts, D’Silva chose to write Lost Danish Treasure in more of an engaging storytelling manner than a straightforward reference or textbook style. Similar to the structure of Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City, the chapters alternate between two different storylines. For Lost Danish Treasure, the two plots are actually connected (no mass murders involved in this book!), as the ongoing research and analysis by the modern-day collectors start to fill in gaps in the historical record of the Chieftain Chair.

|

|

Chieftain Chair in teak with black leather.

A year after the Chieftain Chair was designed in 1949, Juhl entered into a licensing agreement with Baker Furniture, based in Holland, Michigan, to hand produce a line of furniture in the United States. The majority of Baker Chieftains in homes today are from a re-issued production run in the late 1990s. Very few Baker Chieftains were made in the 1950’s, perhaps less than 10, with only 3 or 4 examples that have resurfaced in the public realm in the last 20 years.

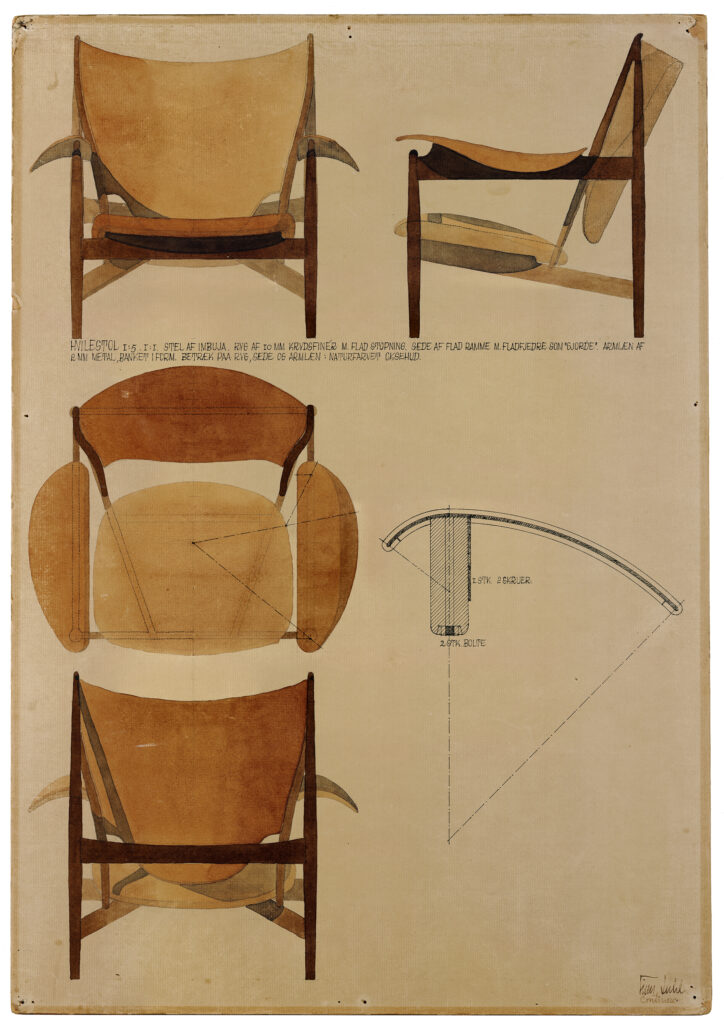

Although an architect by training, Finn Juhl had an earlier childhood love of art. While most architects were presenting their new designs through technical black-and-white ink drawings, Juhl would watercolor his new designs to better convey materials, light/shadows, and color. Copies were often made from original line drawings and then watercolored afterwards for use as either gifts or for marketing purposes. Juhl had famously used watercolors in 1950 to help convince Baker to approve his designs for production, after the black-and-white line drawings initially sent were rejected.

“So, when a Danish modern painting popped up at (Wright Auctions), in the early summer of 2021, there was instant recognition of its content but not of its true origins or significance. The listing description stated it was a watercolor of a Baker Chieftain Chair by Finn Juhl…A 1950s Baker Chieftain watercolor would certainly hang nicely on the wall next to his 1950s Baker Chieftain Chair,” D’Silva thought. Long after the auction had ended, the author learned that this incorrect listing attribution had been provided by the consignor. The Chicago auction location, and apparent connection to Baker, was a lucky break for D’Silva as bidding would almost certainly have been much higher had other collectors realized it was the original concept artwork that Juhl had painted himself for the 1949 Copenhagen Cabinetmaker’s Guild Exhibition. The author likes to make the analogy that this annual exhibition was the furniture equivalent to the Detroit Auto Show, where the public eagerly awaited each year for new designs to be unveiled. Imagine finding the original concept artwork for the Chevy Corvette in Denmark, 70 years after the car was debuted.

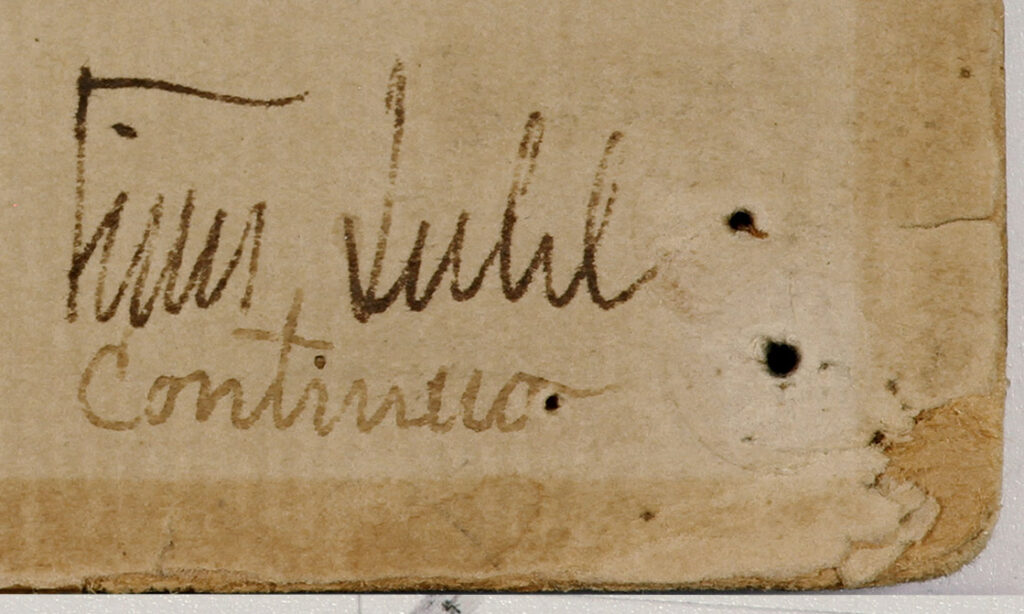

Lower right corner of Wright watercolor after removal from the frame.

Chieftain Chair watercolor – full board

D’Silva has been collecting and researching Danish Modern furniture since 2011. Much of the foundational research for Lost Danish Treasure was done in the following decade, not for the purpose of writing a book, but in order to identify under-the-radar pieces of furniture to add to his collection. His first book captures the construction, in magnificent photographs, of the new Bangkok airport, designed by Helmut Jahn, with whom the author worked during the first 24 years of his career. Currently a Principal at Perkins&Will’s Chicago office, D’Silva wrote late into the night and on weekends to complete his book in time for the release of the limited-edition Chieftain Chair in 2024, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of its release in 1949.

King Frederik IX sitting in Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair at 1949 Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibition.

How did this eye-catching chair receive its memorable nickname?

“During the opening of (the 1949) exhibition, one of the first to try out the chair was none other than Frederik IX, the King of Denmark. A reporter subsequently asked the architect if the chair should then be called “the king’s chair”. Feeling that name was too pretentious for even his healthy ego, Juhl responded, ‘You had better call it a chieftain’s chair.’”

Ironically, Juhl rarely used this name for his most well-known design. He opted for a more low-key name instead, referring to it as his “big chair.”

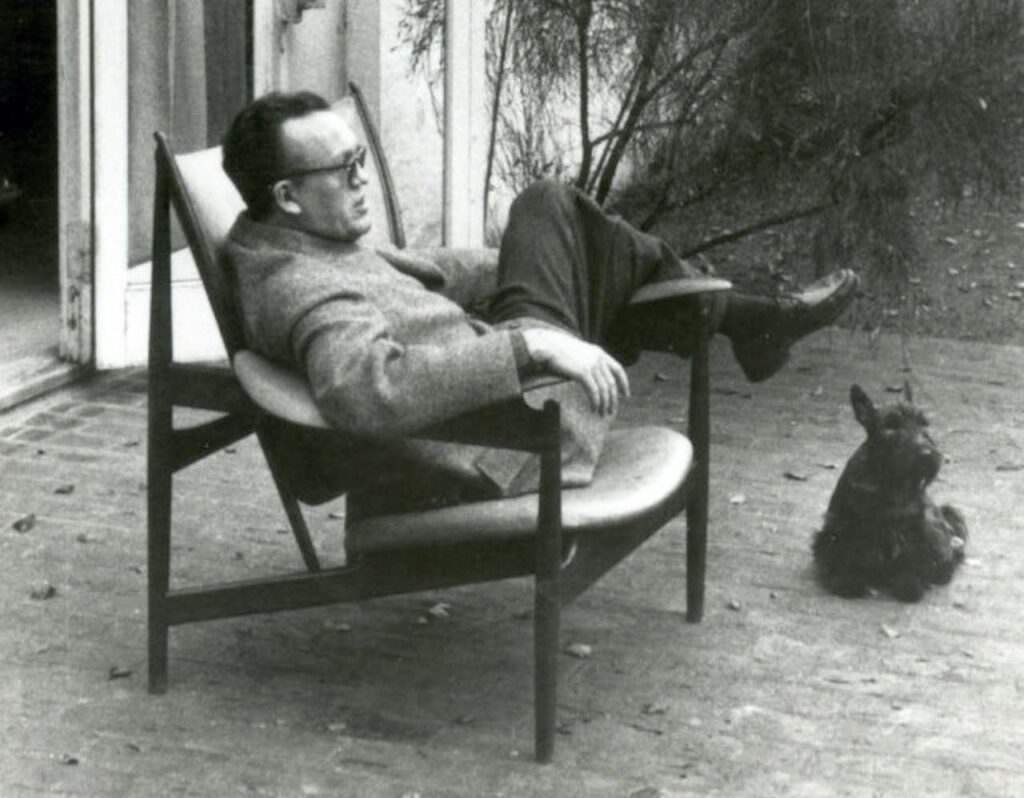

D’Silva noted that the Chieftain Chair was designed with comfort and flexibility in mind. “The seating area is wide enough for the user to reposition themselves as desired, even to the point of unconventionally swinging a leg over the armrest. A vintage photo shows the future Prime Minister of Denmark in such a pose at the 1949 exhibition opening, no doubt prompted by the designer nearby off camera.”

Future Prime Minister Jens Otto Krag sitting with leg over armrest of Chieftain Chair.

Finn Juhl sitting with leg over armrest of Chieftain Chair – patio.

In celebration of the 75th Chieftain Chair, the House of Finn Juhl has released a limited edition of 366 models in smoked oak with a variety of leather types, one for each day of the year, including leap day this year.

How did D’Silva’s love of Danish Modern furniture begin?

“In 2011, I bought a house in Edgewater and needed to furnish it (my previous apartment had a pool table in the dining room). In my search, I stumbled across vintage designs using wood and leather, which were much warmer and more ergonomic than the colder steel designs from Germany that are more associated with early modernism. This was my first introduction to Danish modern. I quickly began my treasure hunts, regularly visiting craigslist, estate sales, and auctions, looking for unattributed gems that might slip under the radar. I realized that although there were many books at the time about older furniture styles, there was very little on Danish Modern. The more I learned, the better chance I would have to recognize and obtain pieces well below their value. The desire to learn more about this style prompted even more research and became the foundation for the eventual idea to write this book.”

D’Silva further elaborates that his hobby extends further than just research and acquisitions. “I also enjoy restoring and photographing most of the pieces in my collection. Both of these processes involve interacting with the furniture up close, often resulting in noticing and appreciating design/construction details previously missed. The necessary step of selling off some designs (to avoid becoming a hoarder) is the least satisfying part of the cycle…but at least I still have photographs that I can pull up whenever I want to see them again.”

Incredibly researched and filled with photographs and drawings, Lost Danish Treasure is a tour de force. While pondering the various meanings of the title, D’Silva concludes the book with:

“The re-emergence of this painting will now help establish a more comprehensive accounting of the chair’s origins. While this watercolor completes the original set of six design competition boards from the 1949 Copenhagen Guild Exhibition, perhaps the greatest treasure that has been found is the reassembled history of the most iconic design in Danish modern: Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair.”