By Robert H. Jordan, Jr., Ph.D.

“When a Clown Retires, He Leaves Big Shoes to Fill: The Funny/Sad Rise and Fall of Bozo, America’s Favorite Clown”

Editor’s Note:

Retired WGN Television news anchor/reporter and author, Robert Jordan (Bob), presented this paper during the 150th year of the Chicago Literary Club. Jordan, who was President that year, chose to write about Bozo since it was such a venerable and beloved institution in Chicago. For those of us who played along with the Grand Prize Game, waited faithfully for our tickets to arrive and loved Bozo, Cooky, Ringmaster Ned and all the rest, the paper brings back sweet memories.

As the aging thespian plopped down at the makeup table, for the last time, he smiled and chortled, under his breath, releasing a small melancholy sniggle. The end had arrived. He stared into the big mirror – which was framed by small, low watt light bulbs – used to make his image bright and shadow free. Each day, he would take this final gaze at himself before undertaking the amazing metamorphosis, a transfiguration he had borne countless times over his fabulous 24-year career: completely erasing his essence. Now in his 60s, he had decided to retire knowing his legs were still somewhat sturdy – not yet wobbly – while he could still get back up after a comedic fall or bodily collision into one of his goofy sidekicks.

After applying a thin protective coat of baby oil to his face and neck, his first step was to apply Clown White makeup all over his face, covering his eyebrows, ears and neck; everywhere except his gray hair. He would carefully approach the edges of his face using a steady, but knowing, hand that almost automatically painted through the intricate areas of the eyes and mouth, displaying an artful dexterity, signaling that this delicate operation had been performed thousands of times before.

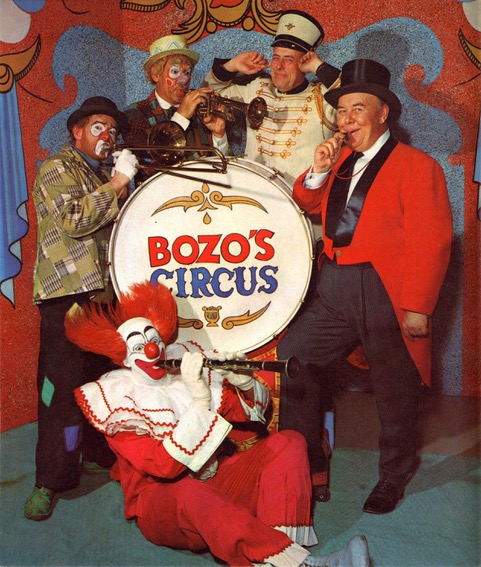

Clockwise starting with Bob Bell as Bozo, Don Sandburg as Sandy, Ray Rayner as Oliver O. Oliver, musical director Bob Trendler & Ned Locke as Ringmaster Ned (1965) Courtesy of WGN-TV & BOZO™ & © Send in the Bozos LLC

Step two was to apply red makeup all over his chin up to his upper lip, extending the natural corners of his mouth to outrageously enlarge his smile to reach up over his cheekbones, giving his newly painted mouth an enormous size.

Step three called for a black makeup pencil to outline all of his facial features – especially, his new black, highly arched eyebrows that now stretched up over his white face to the middle of his forehead. And to protect this fresh Joker face, the makeup was locked in place using white setting powder, applied to lock in all of the colors of grease or cream makeup.

Step four was simple and quick, affixing his round red nose – attaching it with a long string that reached from the nose to the back of his head.

Step five, the final, was dramatic – putting on the famous reddish, almost orange wig which was attached to a large cap resembling a white, over-sized Yarmulke (Yaa-muh-kuh). The white cap would fit snugly over the head, matching the forehead and face, giving him the appearance of a bald clown with orange hair protruding from the sides and back of his head.

With this awesome transformation complete, Robert Lewis Bell, better known as Bob Bell, was no longer the handsome image in the mirror; that reflection was gone. In his place sat a Harlequin, billed as Bozo the Clown: The World’s Most Famous Clown. Why was this such an important moment? Because countless other clowns have been and continue to be ephemeral, while Bozo has had lasting significance for millions of adoring fans and Bob Bell was the most successful. His comedy was simple, clean and funny; It never curdled.

Meanwhile, in a big television studio down the hall from the makeup room, tension was high – you could cut the anxiety with a rubber knife. The floor director, speaking loudly, would shout, “Quiet!” to the anxious and excited crowd of over 200. Hearing that, the fidgety youngsters, squirming in the bleacher seats, would freeze, holding their breaths – sensing for the moment they had longed for their entire lives.

TWEET!! A shrill police whistle would pierce the air in one long burst. Blown by Ned Locke, better known as “Ringmaster Ned,” the sound would stop when Ned would shout his daily alert: “Bozo’s Circus is on the air!” Bob Trendler and his 13- piece orchestra, called “The Big Top Band” would play the familiar opening march – Da da, da da da, da da da da da da. And Ned’s introduction would continue: “With Bozo, the world’s greatest clown…Oliver O. Oliver… Sandy the Tramp…Bob Trendler and his Big Top Band…Ringmaster Ned – that’s me… and a cast of thousands!” …. CHEERS FROM THE AUDIENCE. The booming base voice of Ringmaster Ned would guide the show for the next 55 minutes.

Grand Prize Game contestants with Ned Locke as Ringmaster Ned & Bob Bell as Bozo (1971) Courtesy of WGN-TV & Bozo: BOZO™ & © Send in the Bozos LLC

At the height of his prominence – on WGN Television in Chicago – it is beyond dispute that Bozo the Clown was the most famous, most beloved, most recognizable personality in the country: irrefutable. And the unbelievably popular program on Channel 9 became the most watched locally-produced children’s program in television history. And while there were also Bozo Shows on stations in New York, Los Angeles and eventually, 182 other television markets worldwide, the Bozo on WGN Television in Chicago was the ‘guiding light’ for all the other stations with their own versions, staring the beloved clown.

Since 1960, when the promising Bozo show hit the air in Chicago, several generations of dutiful, almost devout viewers would grow up adoring the delightfully funny entertainer and his gang of mischievous, whimsical, playful, and sometimes slapstick, incorrigible buddies. This kind of undying fanaticism was almost unheard of for a television character. It is not hyperbole to state that for many, Bozo was a deeply venerated personality.

At Channel 9, Steve Novak was one of a series of directors who directed the program, running the operation from the control room. He said the WGN Bozo, played first by Bob Bell, quickly became the leader among all the other Bozos across the U.S. “And there were a lot of Bozos,” Novak said, “throughout the country, but this was the longest running show, and it really set the standard.”

I joined the news department at WGN Television in 1973. This was a time when Bozo’s Circus was at the pinnacle of popularity. Bozo was revered so highly that a “mythology” developed around the program in Chicago, lofting the beloved clown to near divine rank or demigod status.

I remember being told – when I started at WGN-TV – about the waiting list, people endured, as they spent years and years longing for their Bozo show tickets to arrive: seven to 10 years was a normal expected interval between sending off for the vouchers and their eventual arrival in someone’s mailbox. A comparison I heard several times was: Which would happen first, the Chicago Cubs playing in the World Series or my Bozo tickets arriving by mail?

Bozo’s Circus was an hour-long program broadcast Monday through Friday at noon. Many Chicago Public School children who went home for lunch would watch the first half of the show and head back to class right after the Grand Prize Game at around 12:30.

WGN-TV Studio 1 during a live broadcast of “Bozo’s Circus” (circa 1974) Courtesy of WGN-TV & Bozo: BOZO™ & © Send in the Bozos LLC

When I arrived for work each day, the huge parking lot at 2501 W. Bradley Place, on the NW side of Chicago, would be packed with cars. And inside the building, excited families and children would line up in the long hall outside Studio 1, waiting to get in. (Parenthetically, the mid and late 1970s were also the time when Phil Donahue televised his national talk show from WGN-TV. Each day, 200 audience members from his program would also line up in the same hallway with the 200 parents and children waiting for Bozo’s Circus to begin. Donahue live at 11:00 a.m. – Bozo live at noon.

Producer Al Hall ran the Bozo show. He was a funny guy himself, but he had to remain morose and misanthropic, in order to keep the whacky band of loony characters in line. Director Steve Novak said, “Well, they would always try the producer….and Al Hall, who was producing the show for a long time, would always get frustrated when they would go off script, and because of that, they tried to do it as much as possible.”

The supporting cast members changed over the years but Cooky (the kookie circus cook), the number two, was a cheerful, ebullient character who was linked as Bozo’s sidekick. Between them there was constant chatter, like: Bozo to Cooky – “Do you know where I can get a good toupee?” Cooky – “No, not off the top of my head.” The other members of the troupe were lovable but irrepressible clowns who wore lapel boutonnieres that squirted water, when you were asked to smell the rose; had rubber snakes and large spiders in their hidden pockets; or who always carried a squeeze-bulb bicycle horn; and who knew lame jokes and vaudeville shtick, like, spinning plates, juggling balls, and sawing a person in half. All the while they spouted clean, lame humor just right for 10-year-old kids: Cooky to Bozo – “Hey Boze, why do Rhinos charge?” Bozo: “Because they never carry cash.”

Over the years, producer Al Hall perfected the process of rehearsals and had the daily schedule down pat. He explained it this way:

➢ Al Hall– “Our basic daily routine was as follows: At 9:30 a.m., we’d have a read-through of the comedy sketches.

➢ At 10:00, the cast would go in and put on their makeup, and during this time, we’d have the guest act rehearse.

➢ At 10:45, we’d rehearse the live commercials.

➢ At 11:00, we’d rehearse the sketches. We would spend a half-hour rehearsing the sketches and the camera moves. We would always rehearse the sketches in reverse order, doing the last sketch first. That way we knew how long the last sketch would run, so if the other segments ran longer than expected, we could make adjustments.

➢ At 11:30, the cast would go into the dressing room and relax for a few minutes (smoke a cigarette) while we brought in the studio audience; it would take them 10 or 15 minutes to get settled.

➢ At 11:50, we’d start the “warm-up,” welcoming the audience to the studio and informing them about our program. This was cut and dried; it was the same warm-up each day. I did it for 26 years, Hall said.

➢ At about 11:56, we’d bring out the talent and introduce them to the studio audience.

➢ Then, at 12:00 noon, we’d go on the air… whether we were ready or not.”

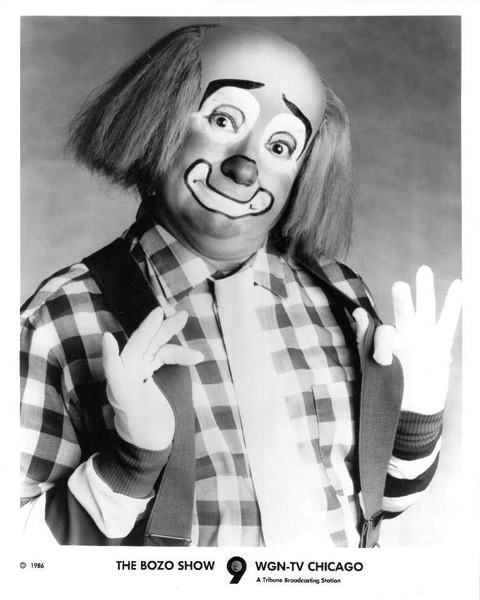

Bob Bell as Bozo (1983) Courtesy of WGN-TV & Bozo: BOZO™ & © Send in the Bozos LLC

Robert Lewis (Bob) Bell1 was born January 18, 1922, in Flint, Michigan. His father was an assembly line worker at General Motors and his mother was a housewife. Bell’s flair for comedic character-acting surfaced in 1953, when he was paired with a variety/talk show host named Wally Phillips at WLWT-TV and WLW Radio in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1956, the stations’ Executive Vice President, Ward Quaal, left the company to become General Manager of WGN Continental Broadcasting Company (WGN-TV & Radio) in Chicago and brought Bell, Phillips and the show’s writer/director/producer Don Sandburg along with him. (Parenthetically, Ward Quaal would hire me at WGN-TV, 17 years later).

By the time Bob Bell reached WGN-TV, the Bozo character had been around for a long time. Alan Livingston,2a writer/producer in Los, Angeles, created “Bozo” for Capitol Records in Hollywood, California in 1946.

George Pappas, who assumes the character of Bozo today, for WGN functions, parades and other purposes, is also a keeper of the records surrounding Bozo. He said, Alan Livingston’s Bozo started with simple children’s entertainment.

George Pappas – “He came up with the idea of a read-along illustrated book. Play the record, and Bozo would tell the story about being at the circus or whatever, and I think he would blow a whistle and every time you heard the whistle you would turn the page.”

Then, Capitol Records sold the Bozo licensing rights to a local entertainer, Larry Harmon, whose business began distributing Bozo animated cartoons to television stations across the country along with the rights for each station to hire its own live Bozo. Harmon was strict about his clown and demanded an almost filiopietistic reverence to tradition.

Even so, Harmon worked out a deal with WGN-TV and Chicago’s Bozo debuted on June 20, 1960. Bob Bell was the star of the, then, live 30-minute “Bozo” show weekdays at noon. He would perform comedy sketches and lead-in to Bozo cartoons. But, in 1961, Tribune Company, which owned WGN-TV, bought a large property in Northwest Chicago and built state-of-the-art television and radio studios there. The program was placed on hiatus in January 1961 to facilitate the big move from studios at Tribune Tower to 2501 West Bradley Place. Then later, after getting settled, the show was expanded to an hour and returned as “Bozo’s Circus” on September 11, 1961. With additional cast members, a 13-piece orchestra, comedy sketches, circus acts, cartoons, games and prizes, the show would now include a live studio audience of more than 200 parents and children.

The most well-known and popular game was the Grand Prize Game. After being selected from the studio audience, a boy and girl would take turns trying to toss a ping pong ball into a straight line of 6-buckets, nailed to a board, each a few feet in front of and away from the child’s reach. One bucket at a time, the boy or girl would attempt to throw the ball into a bucket. The first bucket was the easiest, sitting right at the tip of their toes. Bucket number six, the furthest and last container was about eight feet away. The prizes for each bucket got bigger and bigger up to ‘Bucket #6’ which was a Schwinn bike and the proceeds of a pouch of silver dollars that grew in number each time bucket #6 was attempted and missed. Sometimes the pouch would accumulate a sizable number of silver dollars before being won.

Clockwise starting with Bob Bell as Bozo, Roy Brown as Cooky, Frazier Thomas, Marshall Brodien as Wizzo & Pat Hurley (1983) Courtesy of WGN-TV & Bozo: BOZO™ & © Send in the Bozos LLC

In the control room, with a wall of 10 to 20 small TV monitors, Steve Novak, who directed the show in the the 1990s, would speak over his headset, calling the camera moves to the floor camera crews and also talking to the audio engineer controlling the mics. But most of the instructions would be for the engineer called the ‘switcher.’ The switcher sat – not too far away from the director – in front of a large instrument panel about 3ft by 3ft, containing rows and columns of all kinds of buttons, levers, faders, switches, and twister knobs. Upon Novak’s direction everyone would respond. Novak would call the orders, prompting the switcher to ‘punch up’ the camera or go to another camera next. Producing the Grand Prize Game, over all of the headsets, would sound like this:

Steve Novak – “We would have three cameras. You’d have one camera on the little kid, a camera on the buckets, and a camera to get the audience reaction. So, you would have a camera on the crowd, and it would be – Camera 1. One on the kid, 2 on the bucket.

So, you’d have: quick zoom. Ready one. Open Ned’s mic.

Take one – zoom, ready, 3. Take 3, zoom, zoom, zoom.

The kid would get the bucket, all of a sudden. Then you cut — cut out to the audience.

They’d be pointing away. Take 2. Cut back to the kid, camera one. Take 1. Camera 3 would get the guy getting the prize. Bring in the prize.

Take 3. Then you’d repeat that whole sequence. So, be ready. One, take 1 — ready 3, take 3. Ready 2 take 2. Ready 1, on the prize. Take 1. 3, Take 3. Ready 1 – on the kid, take 1. Ready 2 on the buckets, take 2. Zoom, grab the bucket… ready, 1.”

And while the control room madness was 60 minutes of organized chaos – on the television screen at home – it all worked smoothly; so effortlessly that the funny came through. But since it was live television, there were crazy incidents that happened causing the crew and clowns to break-up laughing while the folks at home had no idea what had happened.

George Pappas – “I remember once this little girl [playing the Grand Prize Game] walked in front of the buckets… would walk up to the buckets, [to drop the balls in] and Ned looked at her and said, ‘Sweetheart, you’re doing great, but you have to stand right here [behind the line] and whatever you do, don’t walk around this way to the bucket.’ So, what does a little girl do? She walks behind him to get to the bucket, while Ned just looked up and stared into the camera. And this is live television.”

Backstage in the enormous prop cage the stagehands stored all kinds of items used in the sight gags: A huge bolder, 6ft by 5ft, that looked as if it weighed a thousand pounds, was made of painted sponge material, making it very light around 10 pounds; plus there were fake rubber chairs, paper brooms, cardboard houses, famous rubber chickens, a confetti cannon and all kinds of play cars, scooters and other kinds of fanciful whimsy. But, by far, the most popular bit or gag – even among the cast and crew, as much as the audience – was the shaving cream pie fight.

The playful brawls were funny because they would usually begin with the calm, quaint and demure Cooky the Clown fixing a phony meal for Bozo and his buddies. Each skit was planned to be open-ended and flexible – knowingly lacking verisimilitude, because, after all – they’re clowns. We know the dinner is perilous and destined to end in chaos when we see Cooky reaching into his large aluminum stock pot, filled with Barbasol Shaving Cream. He dips out a large frothy dollop and sloppily splashes it on someone’s plate. At the same time, Cooky is chatty, asking Bozo, “Hey Boze, how do you divide an ocean?” Boze says, “I don’t know.” To which Cooky replies, “With a seesaw… ha-ha.” Then, Cooky would serve another clown, and some of the cream would splatter on Wizzo (Marshall Brodien) or Bozo and they would shout, “Hey Cooky, be careful, you got some of the pie on my new jacket.” Cooky would snicker, apologize, and have the temerity to say, “It was an accident.” And because this was trivial to Cooky, he wouldn’t quibble. But then, he would dump more cream on the plate of Wizzo who would yell, ”Watch out, with the pie, Cooky.” A band member would pick up a handful of shaving cream and toss it back at Cooky. Cooky would then hurl a paper plate full of suds at Bozo, standing next to the band member. Bozo would duck causing the pie to hit an innocent clown sitting beside him. The astonished jester would throw a handful of cream back at Cooky, who would then flip a large amount in the direction of Wizzo, producing a brawl, with paper plates flying at all of the dinner guests. And while each entertainer knew the skirmish was coming – expecting a bombardment of paper saucers zooming around the studio – they would all act surprised when they were hit. And with each Ka-plunk of a pie-in-the-face, the audience would cackle and hoot and scream and giggle with delight.

Roy Brown as Cooky (1986) Courtesy of WGN-TV

In the vast majority of the raucous pie-fight meles, Bozo would come out unscathed. Most people thought it was because Bozo was the leader and preeminent chief of the group – which he was – but, in reality, it was something much more pragmatic than Bozo being the commander; it was his big orange wig. Bob Bell only had two of those prominent hairpieces and while one was being cleaned and shaped, he’d wear the other one; and the cleaning bill was a big ticket item. So, in a pie fight, the unwritten rule was, ‘don’t hit Bozo.’ Also, at the end of the show, Bozo – like a Pied Piper or Troubadour – has to lead the studio audience out the door.

But by 1984, Bob Bell felt that his age might be an issue if he continued with the sometimes strenuous and acrobatic demands of the show.

George Pappas – “It got pretty physical. But yeah, Bob was in his 60s, and he decided that it was time… because he didn’t wanna do a pratfall and not be able to get up again.”

For that last Bob Bell performance, newspaper, magazine, and wire service reporters were invited to come to WGN-TV to cover his finale, and TV stations sent reporters to do stories. Bob Wallace from Channel 2 – and I – were among those selected to report on Bell’s last show for our respective TV news channels.

As usual, the skit involved Cooky serving a meal to party guests. Everyone sat around a few small, round tables. All of the news reporters, mixed in with the clowns, made for a loosely disreputable yet hilarious mélange of 10 to 12 dinner guests.

As Cooky began serving us all, this day he was especially sloppy – abandoning any semblance of table etiquette – slapping huge drooping servings of Barbersol on all of our plates. (Secretly, I was excited because Al Hall, the producer, had told me the day before not to wear a suit and tie, but rather, put on some old clothes that I didn’t mind getting soiled). So, when Cooky moved next to me and offered to serve my plate, I nervously received an especially large serving of, er, pie which overflowed my floppy paper platter and ran into my lap. But, before I could complain, others at the table had already begun to get, slaphappy with their portions of pie, offering plates-full of soapy shaving cream to others at the table. It wasn’t long before I caught a plate full of pie on the face… and as I carefully scooped the cream off of the side of my eye, I watched Bozo get a foamy quiche to the head, too. As more pies were aimed at Bozo, he would duck, spin and turn, pirouetting out of the line of fine. Then, pandemonium broke out as the maelstrom of zooming pies filled the studio and expanded to outside – in the hall.

Stagehands had been recklessly extravagant, that day, preparing 150 plates of Barbasol shaving Cream for the skit. Studio personnel, camera engineers, studio crews, secretaries, news writers and other WGN employees – from different areas of the TV station – grabbed paper plates and chased each other all over the building. What made it so dangerous was that slippery shaving cream was all over the floor and hallways making walking – let alone running from a pursuing pie thrower – an extremely dangerous undertaking.

And since this was Bob Bell’s last show, the other clowns used this as a rare opportunity, recompensing for decades of forbidden opportunities to crown Bozo with a pie. So, that day, Cooky and the rest of the cast were salivating at the thought of aiming at Bozo. Accordingly, several cream pasties landed in his face and all over his head and – soon to be droopy – big red wig.

George Pappas – “He was covered in pie. He was covered head-to-toe in pie, and he led the grand march finale completely covered in pie.”

According to IMDb.Com, “The Bozo Show and Bell’s portrayal, over his career, achieved a popularity and success unlike any locally produced children’s show in the history of television3.The program began airing nationally via cable and satellite on the Superstation, WGN-TV, in 1978.”

WGN Television had already begun a nationwide search for Bob Bell’s replacement. Joey D’Auria, who had worked in theater and who understood vaudeville was eventually selected. Joey told me a story about the first time he auditioned, and Roy Brown, who played Cooky, offered Joey a challenge, to see if he knew clown vernacular, standard routines and could ab lib. Roy spoke to Joey and said, “Boy I just broke my leg in three places.” Joey looked at Roy and smiled saying, “Well, you’d better stay out of those places.” Ka-Boom, Rim shot!

They all laughed. Joey had replied in a manner as though he had answered a secret fraternity salutation, an initiation affirming that he was a member in the imaginary “Mistic Order of the Clown Brotherhood” or something.

Bob Bell (1986) Courtesy of WGN-TV

Joey knew all of the well-known material of Henny Youngman and Rodney Dangerfield, and knew how to deal with a bad joke that fell flat, like “Why did the chicken cross the playground? To get to the other slide”… applause.. Thank you, thank you, I’ll be here all week, try the veal… and don’t forget to tip your waitress.”

And sure enough for his 17 years, assuming the role as the world’s most famous clown, Joey D’Auria was a very popular Bozo who kept alive the magical glow surrounding the clown’s image.

I’ll never forget one time, Joey, dressed as Bozo, news anchor Steve Sanders and I were riding in a stretch limo – leaving WGN-TV – heading to the Bud Billiken Parade. As we pulled onto the Kennedy Expressway, our limo driver accidently cut off a little old lady driver in a tiny car. We were sitting in the back and could see that she was almost run off the road. Boy was she angry! Once we were on the expressway, she pulled alongside our limo and began giving us the middle finger – again and again, with gusto – she continued to flash her hand at us. Then, Bozo lowered our dark-tinted window to reveal his smiling face, while dexterously waving both hands at the women. Once she noticed that she was flashing “the bird” at Bozo the Clown, immediately her face changed from raging anger to a shameful, deeply apologetic smile… and then she screamed, “Hi Bozo… I’m so, so sorry!” As Boze raised the window, we all laughed – all the way to the parade. The old lady was probably the only human in the history of the world who had used a rude hand gesture, menacingly at Bozo the Clown.

But Bozo would tell you that, over the years, his clown personae had affected people in different ways: especially children.4 Bob Bell often talked about how he knew to cautiously approach toddlers. Babies in arms were especially prone to anxiety and would lean away, grabbing their parents around their necks for security, often emitting bloodcurdling screams in fear.

As I dug deeper into the phenomenon of adults fearing clowns, I learned that there is actually a term for such an aversion, called Coulrophobia – a condition in which children and adults who fear clowns may experience extreme, irrational reactions when they see clowns in person or view pictures or videos of clowns.5

Playwright, William Shakespeare often used the characters of fools or clowns in his plays. These eccentrics were usually clever peasants or commoners who used their wits to outdo people of higher social standing. Their characteristics were usually greatly exaggerated for theatrical impact. Shakespeare portrayed two distinct types of fools: those who were wise and intelligent, and those who were ‘natural fools’ (idiots that were there for light entertainment). Shakespeare himself did not say anything specific about clowns, but he used them as a tool to comment on society and the human frailty of not truly understanding the nature of comedians.

This idea of not sensitively decerning how or what a clown feels on the inside is also the basis of a grand opera, Pagliacci, by Ruggero Leoncavallo. First performed in 1892 – the dark comedy tells the story of a clown, a Pagliacci in Italian, a Payaso in Spanish – named Canio, who overhears his wife and her lover make plans for a later rendezvous. Canio, who is an actor and leader of a commedia dell’arte theatrical company, later, murders his wife Nedda and her lover Silvio on stage during a performance. But earlier, in Act l, Canio is in his dressing room, grudgingly preparing to put on his costume. He sits and stands in front of the mirror, knowing that his life and marriage are ruined and sings a famous aria, Vesti la Jubba, translated as: “Put on the costume”, or sometimes translated in English as “On With the Motley.” Motley is the traditional costume of the court jester, the motley fool.

In the opera Pagliacci, the aria Canio sings, with palpable pain and grief, is often regarded as one of the most moving in the operatic repertoire of the time. While emotionally cry/singing, and uttering a ‘sort of’ recitative, Canio gasps, and gurgles-out the lyrics. The intense agony Canio feels is shown in this special piece of music and exemplifies the conflicting notion of the “tragic clown:” smiling on the outside yet crying on the inside. Canio exemplifies the contradictory concepts of happiness and heartbreak shown in the Greek masks of comedy and tragedy – Thalia and Melpomene, a misfortune that is expressed in an unbearable simultaneous, double existence. So, this idea that clowns are by nature schizophrenic – a person underneath another personae on the outside – can be unsettling to some people.

Over the years, Bob Bell made changes to Bozo, feeling the clown needed to be less glaring. In 1970, his costume color was also changed from a loud red to blue to match the cartoon character. He also softened the eyes, making the eyebrows less graphic and more human-like.

After replacing Bob Bell, one of the first things Joey D’Auria thought about was that he would have big shoes to fill while continuing to achieve tiny ‘transformations in style’ without making Bozo avant-guarde. Then, he realized that new wigs had to be made.

Joey D’Auria – “And so my wife suggested that I contact the Lyric Opera here in Chicago, and I called them, and I met with their wig man, and he introduced me to one of his assistants, and he was happy to take the job.”

Yet, with new management at WGN Television, who were cost-conscious executives, trying to lower expenses, The Bozo Show, with all of its unforeseen expenditures, would – for the remainder of its broadcast life – be a large target for the “merciless bean counters,” causing the tapings to undergo belt-tightening.

In 1980, the series moved to weekday mornings as “The Bozo Show” and aired on tape delay.

But cuts to the program budget had already begun to strip-away some of the luster, sparkle and unique qualities of the show. Bob Trendler and his 13-piece, ‘Big Top Band’ were the first to go in 1975. They were replaced by a trio – a trumpet player, an accordionist, and a drummer. They were around until 1987 when WGN hired a one-man-band – a very talented musician named Andy Mitran, who played a synthesizer – a musical instrument that has a keyboard like a piano but can sound like just about any instrument or group of instruments.

Left to right starting with Robin Eurich as Rusty, Joey D’Auria as Bozo, Michele Greory as Tunia & musical director Andy Mitran as Professor Andy (1996) Courtesy of WGN-TV & Bozo: BOZO™ & © Send in the Bozos LLC

Plus, TV management made the show’s format educational in 1997, when the federal government, through the Federal Communications Commission, (FCC), enacted new rules that dictated broadcast television stations to air a minimum three hours per week of “educational and informational” children’s programs.

Washington, D.C. had its own Bozo – Willard Scott – who years later was a weatherman on NBC’s Today Show. His Bozo went off the air in 1962, after three years.

But, Chicago is where the celebrated clown lasted the longest and it is where WGN’s Bozo show met its end after more than 9,500 shows.

During my 45-years reporting the news – mostly at WGN Television – I would sometimes, come across someone who had been very helpful to me on a news story or who had suffered through an awful traumatic event. I could, on very rare occasions, soften the severity of the moment by getting their names and addresses and whispering that Bozo tickets would soon be arriving for their grandchildren. It would be amazing to see their eyes brighten and a smile crack the corners of their mouths, just knowing that Bozo tickets were on the way. With all of the fame and celebrity, Bob Bell could easily have become smug and pompous, but instead he remained modest, humble, and easily approachable.

WGN’s famed Bozo show was one of the longest running and most cherished children’s programs on television. Tickets remained in such demand that expectant mothers – once they had a positive confirmation of their pregnancy – would order the tickets, hoping to receive them when their child was seven to 10-years-old. Even so, station executives continued to downgrade the program on the TV schedule and nip away at its budget – squeezing all of the funny out of the show.

Still, honors continued to pour in. In 1996, Bob Bell and, in 1993, Roy Brown as Cooky were inducted into the International Clown Hall of Fame in Delevan, Wisconsin. There, they joined the Pantheon of great clowns who have made us laugh. All the funny clowns have, since, had their entertainment genre sullied by creepy clowns like Krusty the Clown on The Simpsons or the ignominious clown, John Wayne Gacy, who murdered, and tortured 33 teen boys and men or “Pennywise” the demonic character in Stephen King’s classic horror novel “It,” in (1986). Clowns have come in all varieties.

Then in 2001, the nagging fear of cancellation became a reality. Management at WGN Television decided that continuing with The Bozo Super Sunday Show was too costly and that some of the resources used to produce the locally generated show could be applied elsewhere. In TV parlance, “they pulled the plug.” Two names that had become inextricably connected: Bozo the Clown and WGN Television – which now billed itself as, “Chicago’s Very Own,” – were parting ways… severed forever.

Bozo went from being a daily staple on WGN-TV to being relegated to early Sunday mornings. Now, the treasured clown’s time had run out. The funny friend to generations of television families – who loved watching the warm-hearted clown with the chalk-white face – were stunned to see him go away. Smiling on the outside, yet crying on the inside, this Chicago Pagliacci, experienced the duality of comedy and tragedy.

Station management had made the decision to put the nation’s most-beloved TVclown out to pasture, leading one local columnist, Robert Feder of the Chicago Sun-Times, to accuse station general manager John Vitanovec of “[selling] out generations of fans” and to label him, “The Man Who Killed Bozo.”

“After 40 years,” Feder wrote, “gone will be Bozo, Rusty, and Professor Andy. Gone will be the Grand Prize Game. And gone will be a piece of our fondest childhood memories.”

The Bozo Show’s time had come and gone. The improbable icon known for absurdities on one hand and good, wholesome, enjoyment on the other was left to ‘load up’ all of his circus friends into the clown car and drive away.

Simply stated, Bozo was a Luddite. A character and a program mired in the past and present, yet unable to accept new forms of comedy. But the clown’s simplistic approach towards humor – the prat falls and pie fights and water guns and ‘Ooga horns’ – is what made millions of innocent children love him so much. It is why Chicago television became famous for children’s programming: frayed around the edges and all.

When the last day arrived, there was gloom all over the TV station. The great Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, who understood melancholy, would have characterized it as, ( ”La tristesse jur-ha por- to-zuor .” (The sadness will last forever). The wretched day they taped the final Bozo Show, it was left up to WGN-TV director, Steve Novak, to administer the coup de grâce. Speaking over headsets, to his team of camera operators and engineers, it sounded like this:

Steve Novak – “That day, Bozo said… “And now, one last time, it’s the Grand March.”

“We had a shot of Bozo. We cut to a wide shot. Bozo danced and strutted past the camera, leading the audience out the door.”

Novak continued to speak to the crew:

“Everyone ready – on Camera two – take 2. Ready Camera 3. Take 3. Ready, one. We watched, the kids all file by. Be ready to take it when we see there is a nice family group. There … Camera 1.

All right. Ready 1. Take 1. Ready 3. Take 3. Then, the last two kids of the day marched by. Be ready. (I said, with my voice cracking) Wow! This chokes me up! Take the two last kids, holding hands.

Kill everybody’s mic. Ready to slowly fade… fade to black… aaannnd we’re done! Nice job everybody! That’s a wrap!”

The End

1IMDb – Bob Bell, Biography

2IMDb – Alan Livingston, – Biography

3IMDb

4 “Fear of clowns in hospitalized children: prospective experience.” National Library of Medicine. Eur J Pediatr, 2017

5 Coulrophobia (Fear of Clowns) 100 Years of Cleveland Clinic.

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21835-coulrophobia-fear-of-clowns