The author with Roger Fry’s daughter, Pamela Diamand; Pamela’s husband, Micu Diamand; and

By Lucia Adams

In 1967 during a stay in Cambridge I discovered Roger Fry’s papers were in King’s College Library a bequest to his alma mater after his death in 1934. I revered his art criticism in Vision and Design, Transformations, and articles in the Burlington Magazine so this was a truly serendipitous thrill. In the stunning 15th century library, I met A.N.L. “Call me Tim” Munby the librarian who permitted me access to the heavy green solander boxes of Fry’s papers. Munby had been a prisoner of war in Germany and was a mystery writer and a poet. In a response to Hilaire Belloc’s Lines to a Don, lamenting the twilight of dons, he composed Remote and Ineffectual Don, (here’s a selection) with its update on British Academia, “Where have you gone, where have you gone? Don in scarlet, Don in tails, Don in advertising Daily Mails . . . Don talking on the Woman’s Hour . . . Don judging jive at barbecue . . . Don not afraid to have a bash, Don with Bentley, Don with Rolls, Don organizing Gallup Polls, . . .Don Christian-naming with the Stars, Don talking loud in public bars, Remote and ineffectual Don, Where have you gone, where have you gone?” Tres amusant, non?

In those twelve solander boxes were Fry’s Apostle Club papers, autobiographical fragments, lectures from Oxford, Leeds, Dunfermline and Bangor, the Fine Arts Society talks, fine watercolors (no wonder he embraced art), letters to Goldsworthy Dickinson and Edward Carpenter, to his mother Mariabella and sister Margery and to many Bloomsburries. Munby arranged a viewing of Fry’s large landscape paintings from the 1920s and 30s in the King’s collection and we carried them one by one to the lawn from Simon Raven’s digs (previously Maynard Keynes’) where I photographed each big canvas and learned that Fry considered himself first and foremost an artist and critic by financial necessity only. I wrote in my journals, to be a creator oneself rather than talk about someone else – no wonder Fry insisted he was a painter first then a critic . . . truly a Romantic by nature he trusted his heart’s affections and did what they dictated.

One day Munby introduced me to a tall, robust fellow reading Fry’s papers at the next table. Quentin Bell, researching the biography of his aunt Virginia Woolf, was then Professor of Fine Art at the University of Leeds, and an artist devoted to his teacher Roger Fry. He was genial and willing to help me before Bloomsbury became a cottage industry and he was hounded by legions of graduate students. After we viewed Rubens’ Adoration of the Magi in King’s Chapel, “this immense And glorious work of fine intelligence” (Wordsworth) he suggested I write a thesis about Fry’s paintings under him at Leeds. I did just that in 1967 when my husband and I moved north.

Lee and I drove to the sea salt town of Maldon on the Blackwater Estuary in Essex, where George Washington’s great-great-grandfather Lawrence is buried, where Fry’s daughter Pamela Diamand and her husband Micu lived. The Bloomsbury Boom was just beginning, Holroyd having just published the second Strachey volume, and Pamela was anxious to sell her father’s paintings which had never done well at auction. Over the next two years we paid four or five visits to Bouchernes, removing the bread wrappers Micu printed in the garage, his business being commercial printing, from the paintings and photographing them.

Bouchernes, a lovely old stone house (R.F. chose it for her) bursting at the seams with pottery and paintings by her father . . . . . the careful way she has looked after RF’s things. I still have the paintings she gave me that day, a 1915 watercolor in the manner of Cezanne which misinterprets how little squares of color should suggest space, the other an unfinished oil of the Bay of Naples from the early thirties. During one visit to Denys Sutton, the editor of Apollo, was reading Fry’s correspondence for his upcoming book. In the book he included a letter that Hubert Waley, brother of the poet Arthur and a fine gentleman from Devizes, Wiltshire, had given to me. He did not by the way, acknowledge my ownership.

Here it is:

“Durbins.

Guildford.Aug.26.15

Dear Waley (May we drop the Mr.)

I am a brute never to have written. I was off with my two children. I left everything else out of my mind for the time, but your letter gave me great pleasure. I liked the poetry of it very much. It’s pleasant to talk so easily across that gulf & perhaps one day we’ll make a bridge-p’haps not. We needn’t bother.

I think Art is like religion – I’m not at all sure it isn’t the same thing or rather an outcome of the same emotion – the emotion of the universal. Anyhow I think religion ought not to be mixed the (sic.) morals or treated as subservient to them. And similarly, Art. I’m sure that morals are part of the mechanism of life. You can think of an amoral world. Indeed, I suppose no Paradise would be much good unless morals were left at the door. i.e., ethics are not an end in themselves whereas the emotions of religion & aesthetics are ends in themselves we should want to go on having them after the other of duty had ceased to have any meaning.

It is something like that I think makes me say art doesn’t begin until you’ve got past the stage of ethics. Ethics is the balance of conflicting claims, art is a free expression.

I think I’ve got this all a little muddled & it might come clear in conversation. I shall be back in town from Sept. 1-4 & then again later. What chance of seeing you.

Yrs. Very sincerely,

Roger Fry.”

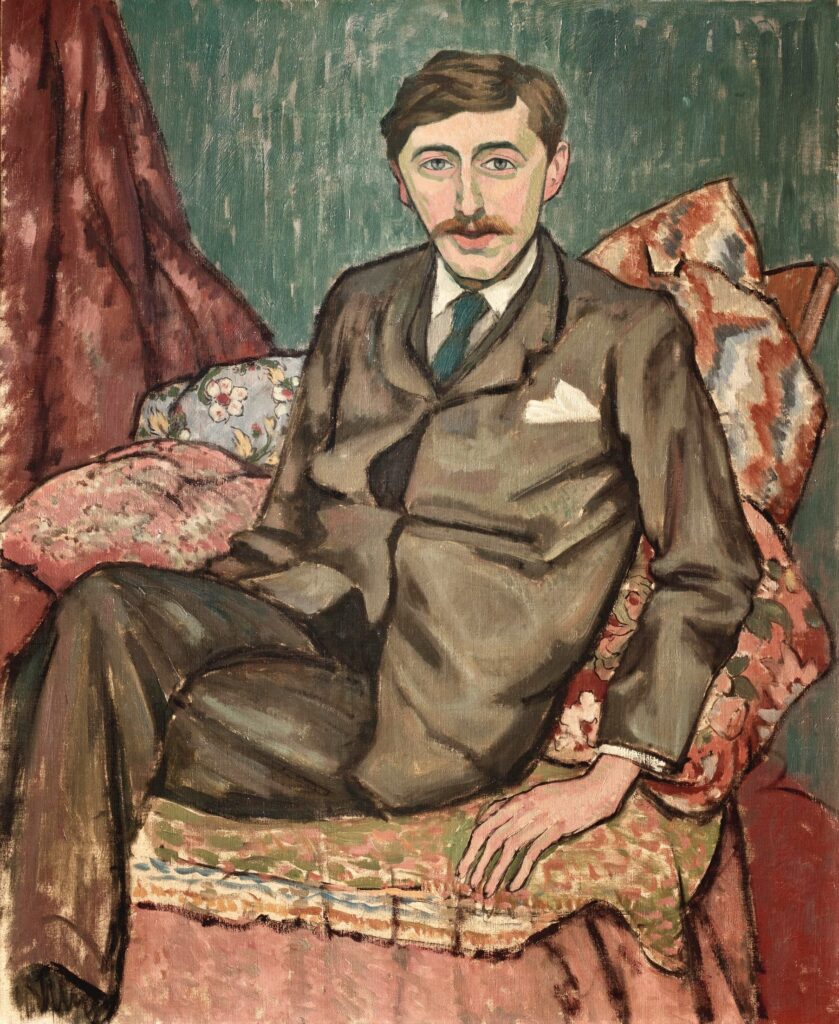

E. M. Forster painted by Roger Fry

While In Cambridge I visited E. M. Forster in his digs at King’s, a crowded Victorian room with a reproduction of Picasso’s Garcon au Cheval on the far wall, where he had lived as an honorary fellow since 1946. In a dark room sat a small old man with a disjointed hip: E. M. Forster. How bizarre to see a tangible living emblem of the past – all I could think of was: he saw this, he must have lived through that . . . His generation would have looked with horror on today’s crude cynicism and nihilism . . . there’s always room for hope in his works . . . He must have been a quiet introspective man – from our brief conversation I could tell he was not one to mince words, was extremely straightforward with no obtrusive ‘personality’ . . . he didn’t much care for Fry’s work but obviously adored the man.

Just recovering from a fall and rather dozy, he paraphrased his own description of Fry’s 1911 painting, “you have a bright healthy young man without one hand and very queer legs, perhaps the result of an aeroplane accident, as he seems to have fallen from an immense heigh on to a sofa.” Bloomsbury was just a group of friends who occasionally saw one another, but without a common aesthetic and so on. Over the tea and shortbread and in the company of his caretaker, I felt like a voyeur and cancelled future visits to Leonard Woolf and Duncan Grant which I naturally now regret.

When we moved north, I took Quentin Bell’s suggestion to write a thesis under him at Leeds on the paintings of Roger Fry which I did, using all those photographs I had taken, and he urged me to write a catalogue raisonne for the Ph. D, but I did not another of life’s big mistakes. I kept in touch with him when he moved home to be professor at the University of Sussex and some years later invited him to give a fundraising lecture for the John Ruskin Appeal Fund to restore his last home, Brantwood on Lake Coniston.

In Abbot Hall, Kendal Bell gave a humorous lecture “John Ruskin and James Burdon” the tale of the great sage’s St. George’s Guild and its utopian dreams which clashed with reality when a locomotive engineer James Burdon quit his job to join the guild and almost starved to death. Ruskin tried to find his apprentice another job—on the land of course—but he ended up going to jail for forging The Master’s signature all of which is related in Burdon’s Reminiscences of Ruskin. The lecture did not raise much money for Brantwood since I counted eighteen people in the audience. The next day we drove Bell and his wife Anne Olivier, the daughter of A.E. Popham, Keeper of Prints at the British Museum for a tour of the north. They had never been there before. We visited Rydal Mount and Dove Cottage and of course Brantwood. When forty years later in 2016 I returned to Brantwood it was still in need of renovation, but I thought just perfect, remote, romantic, another world. Like my past.