By Francesco Bianchini

There was a time when the simple gift of an orange made my day. Along with chocolate and nougat, an orange helped fill my holiday stocking, which I’d leave in front of the fireplace on the night of January 5—the same ritual as by children all over central and southern Italy. Of course these ‘Old Christmas’ treats were only for kids who’d behaved well, never for naughty children who’d find nothing but lumps of coal. And the gifts were not from the Three Kings—the magi of Bethlehem—but from The Befana, an Italian sort of female St. Nicholas who, like Santa, also slips down the chimney. It was every family’s duty to welcome that wise and kind old crone, and the room where she was expected might be the only one heated, wherein she’d find a few pieces of fruit, some sweets, and a glass of wine to cheer her on.

Moment of truth: the Befana assays the naughty and the good (from an early 19th century Roman engraving)

Our holiday oranges were not ordinary ones, but Sicilian tarocchi—the blood-red variety exclusively cultivated in the plains stretching between Catania and Syracuse, harvested in those beautifully manicured fields lying in the shadow of Mount Etna. The oranges were transported north in crates, arranged in layers separated by straw or shredded paper, each fruit individually wrapped in colored tissue paper—except for one in one corner, its bare crimson rind leaving no doubt they were all the genuine article. That unwrapped orange stood out, its taut skin tinged with garnet red, and exuding a sharp, intoxicating aroma.

Pride of Sicily

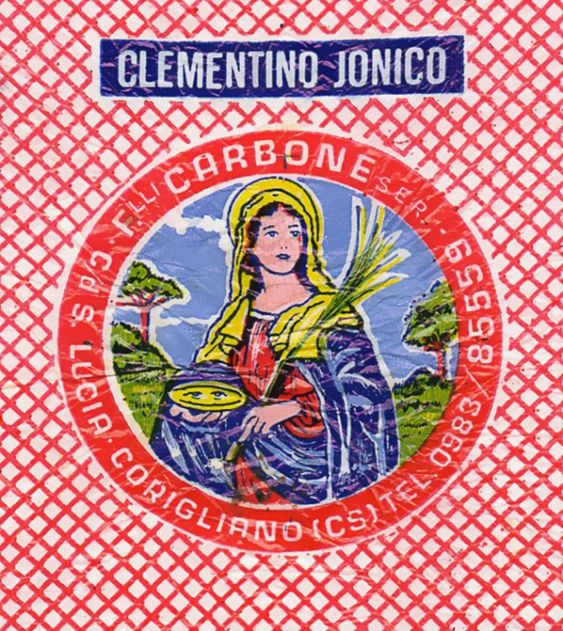

I was particularly enchanted by the tissue paper wrappings. On each, a scene unfolded: a rustic maiden holding bunches of red berries; the Three Graces plucking golden-hued fruit from a small tree; a girl carrying a basket overflowing with citrus. There was a lady with an embroidered mantilla, her blouse suggestively highlighted with naïve strokes, who stood admiring neat rows of red-dotted trees from an ornate balcony. And a Moorish woman with glossy skin and hooped earrings, as well as other depictions of traditional Italian costumes. Some papers bore exotic imagery: a yellow panther speckled with rust-colored spots that could be mistaken for the fruit it concealed; a lion with a ferocious yawning maw, but somehow an amiable expression; or a lancer astride a jet-black horse, his crimson cape billowing as he brandished a reddened orange, just where the severed head of an enemy might have been. One wrapper, clearly destined for export to countries that consider Italy as a land of exotic produce, featured the jester Till Eulenspiegel dressed in red, astride a split orange, surrounded by the iconic vistas of Italy—Rome, Venice, Naples, and Florence—the same sort of views once displayed in black and white posters above train seats. Most haunting of all was the image of Santa Lucia, patron saint of Syracuse, posing against a backdrop of azure skies and parasol pines, with the palm of martyrdom resting delicately on her shoulder, and in her hand a small dish bearing her eyes.

|

|

|

|

|

Each one tells the tale

The memory of tarocchi and their wondrous wrappings takes me back to our old dimly-lit dining room, warmed in winter months by the fireplace and a top-loading, coal-fueled, cast-iron Becchi stove. Its walls were lined with gleaming copper molds and ancient cookware, and the beams above studded with small copper bowls resembling rows of pendulous udders. For me, the pleasure lay in unwrapping the oranges and admiring the wrapper designs, sounding out their inscriptions, syllable by syllable: La Favorita, La Morena, Sanguinello, Sanguigna, Moro; and the town names, usually misplacing the accents: Francofonte, Scordia, Palagonia, Paternò, Valverde.

‘Polished wood and gleaming copper

‘Polished wood and gleaming copper

Around the table, we children would beg my father to peel an orange in the way that only he could: fashioning a little basket from the rind. He’d make two incisions on the sides, then deftly extract the pulp without breaking the strip of peel that served as the basket’s handle. For us, the operation was fraught with suspense—a test of papa’s reputation as a master craftsman—and he delighted in astonishing us with such feats. Like splitting a large walnut into two perfect halves, filling them with melted wax, embedding two or three toothpicks, and attaching small rectangles of white paper marked with red crosses—Columbus’s fleet of caravels en route to the Indies!

And we’d squabble and fight over his creations, and occasionally the fragile handle of the orange basket would snap during our disputes, or the ship’s sails come crashing down. Whoever managed to grab the thing would tease the others, holding the broken bits together. ‘Broken or fixed? Broken or fixed?’ we’d taunt. My mother hated the riddles we invented for every possible item—be it a piece of bread or a potato chip. ‘Why do you say fixed?’ she’d demand. ‘Say broken or whole.’ We’d answer incorrectly, on purpose, so that our siblings could reply, ‘Faked you out, faked you out, made you eat a Brussels sprout’! This was, after all, the era when silly rhymes and the nicknames we invented—Mary with the eyes so scary—added flavor to our everyday world.

Me and my magician

After a meal my grandmother Margherita would absentmindedly smooth anything she could get her hands on: a napkin, the foil from a chocolate, or the tissue paper from the oranges; a gesture perhaps unconscious and superstitious, that gave her the illusion of ironing out life’s troublesome creases. Once the tissue was smoothed—especially its ends that had been crimped around the fruit like twin navels—my father would perform something else that left us spellbound. He would set one edge of the tissue alight with a match, and it would rise from the plate toward the ceiling, alive with flame, like a tiny hot air balloon that burned quickly and left behind only a delicate fragment of ash—weightless, insubstantial, like the conclusion of a dream.