By Lee Shoquist

The meteoric rise of Barbenheimer—a term that now resonates across the cultural landscape—has breathed new life into the American movie box office, infusing the summer slump with an unexpected surge of excitement and significance. Amidst the disappointment of several high-profile films failing to meet financial expectations, the combined box office triumph of Barbie and Oppenheimer emerged as a stunning one-two punch, amassing a staggering $244 million in opening weekend receipts.

Barbie, Greta Gerwig’s insightful social satire on gender dynamics and womanhood, raked in an impressive $162 million, while Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s sprawling character study of atomic bomb creator J. Robert Oppenheimer, commanded a formidable $82.5 million—a true cinematic coup that defied earlier box office tracking projections to fuel one of Hollywood’s all-time highest grossing movie weekends.

At the heart of this astounding success lies the Internet meme phenomenon known as Barbenheimer—a viral campaign fueled by co-branded posters, memes, and faux merchandise, seizing upon the serendipitous, shared release date of these unlikely companions. The public consciousness was galvanized as this campaign unfolded, with even the filmmakers themselves, including Greta Gerwig and star Margot Robbie, partaking in the fervor by sharing Instagram selfies after securing advanced tickets to Oppenheimer.

Surprisingly, despite their apparent dissimilarity, Barbie and Oppenheimer share common DNA—both crafted by visionary directors, both original works unbound by the constraints of well-trodden franchises or sequels. These fresh ideas have drawn audiences back to theaters in droves, heralding a welcome resurgence of original screenplays and a boon for the commercial entertainment industry.

In the wake of this gargantuan success, several false narratives have been resoundingly dispelled. The notion that post-COVID audiences no longer venture to theaters and prefer to wait for streaming has been proven wrong. Additionally, the misguided belief that films with progressive themes are doomed to fail financially—often touted as “going broke” for being “woke”—has, in the case of Barbie, been decisively refuted. Ultimately, Barbenheimer’s triumph underscores the enduring appeal of well-crafted, adult-oriented movies that challenge conventional norms and resonate with sophisticated audiences.

Moreover, the success of Barbie has shattered the stereotype that projects led by women or centered on women’s experiences can be commercially derailed by male internet trolls, try as they have. Both films have showcased the power of authentic storytelling, untethered by stereotypes or pandering to the lowest common denominator. At the same time, Oppenheimer, a largely cerebral, three-hour film containing heady, scientific theory and labyrinthine plotting, attracted both large crowds and high audience exit scores.

The resounding triumph of Barbenheimer serves as confirmation that commercial success need not sacrifice artistic integrity. It may be too soon to tell, but it could just herald a new era in the American film industry, where originality, creativity and bold visions find eager audiences and reaffirm cinema’s place in our cultural dialogue.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the movie year—or two of them—is that Gerwig’s much-anticipated Barbie has become a runaway cultural moment in a way a movie hasn’t landed in the zeitgeist in perhaps years, and that—delightfully—it’s actually good (and frequently very good).

In a picture that was kept under wraps by studio Warner Brothers until the week of release, director Gerwig, who co-wrote the screenplay with Noah Baumbach, has eschewed mere product marketing tie-ins in favor of a funny, incisive and surprisingly touching meta-level picture, a social comedy about the impossibility of women’s roles in the modern world and perhaps the most pointed American satire in recent memory. While painted in candy-colored pastels and rendered in mostly broad strokes, Barbie‘s sociopolitical critique does not pull punches in a movie that is commercial and subversive, inventive and more than a bit magical.

It takes a moment to settle into Gerwig’s hyper stylized, outsized and uber-performative vision of a “Stereotypical Barbie” who ultimately buckles under the unrealistic expectations of womanhood before developing an enlightened new consciousness. Yet once you do, Gerwig’s sure-handed grasp of tones, themes and bold aesthetic is unmistakable. The movie is also a shot of summer movie fun, and then some.

Picture opens in the plastic-perfect utopia of Barbieland, superbly conceived by production designer Sarah Greenwood and lensed by two-time Oscar winning DP Rodrigo Prieto, where all Barbies (including Pregnant Barbie, a Mattel misadventure) exist in perfect harmony. Theirs is a world of the highest accomplishments: Barbie presidents, Nobel winners, doctors and novelists comprising this genius-level world of women.

Stereotypical Barbie, whom “everybody thinks of when they think of Barbie,” is brought to bouncy, buoyant life by a winning Margot Robbie at her comic best, a model of perfect grace and beauty in a magical world where every Barbie, played by the likes of a smart Issa Rae, Hari Neff and even popstar Dua Lipa, lives in her super saturated Dream House, each a model of aesthetic perfection. They are also superiors to Barbieland’s many Kens, including a scene-stealing Ryan Gosling, a blonde and muscled beach boy, and Simu Liu, displaying a real flair for comedy, each of whom spends his days on the beach hoping to impress Barbie and thus win her affections.

Trouble brews in paradise as Barbie’s perfect existence tilts on its access, her mind drifting to thoughts of mortality, morning shower going cold, feet flatly touching ground and—egads!—cellulite! Enter Weird Barbie (played with signature whip-smart elevation by Kate McKinnon), outcast since her human owner in the real world chopped her hair, bent her into permanent splits and otherwise abused her former visage. Barbie’s solution, according to Weird Barbie, is to enter the real world and track down the little girl who owns her, a reconciliation that will restore her to perfection.

Gosling’s Ken in tow, Barbie lands on Venice Beach, and it’s here that the film picks up satirical steam as the pair, rollerblading in blindingly colored 80s’ spandex, quickly observes this strange new world where men hold the power—one where Ken can’t seem to get a job but nonetheless learns about a little notion named the patriarchy. Barbie teams up with a cynical adolescent (Ariana Greenblatt) who deems her a symbol of “fascist” capitalism and beauty standards, and the girl’s frustrated Mattel exec mother played by a very good America Ferrara, delivering a pungent monologue about the quagmire of being a modern woman (which received applause at the screening I attended).

Barbie also lands at creator Mattel, where we meet CEO Will Ferrell (on his A-game) and a suited-up team of white executive males deciding—what else?—Barbie’s livelihood. Yet instead of assisting Barbie with her real world dilemma and growing confusion over its upside down gender roles, their solution is to carefully coerce her back into her life-sized product box and whisk her back to Barbieland.

Barbie and company eventually do find their way back to Barbieland, where things have radically changed, Ken having brought real world patriarchal attitudes back to paradise, where the Kens now have all the power and Barbies have been brainwashed, relegated to suppress their former independence. It’s here that Gerwig takes on modern gender warfare by savagely, comically condemning straight male fragility and objectification of women, and what accomplished women must give up to cow-tow to the male ego. Meanwhile, the new Kens—all toxic macho posturing and battling each other for dominance while attempting to change Barbieland’s government and constitution—are oblivious to the Barbie uprising happening right in front of them.

Across this very winning picture, Robbie, a marvel of comic prowess, evolves from plastic dream girl to radiant real woman, facing an existential crisis of her identity and place in the world. Should she stay in the safe, “perfect,” female led Barbieland, or make her way into the unpredictable real world with all of its patriarchal imperfections? In the picture’s closing scenes, where a great Rhea Perlman shows up as Barbie inventor Ruth Handler, Robbie brings real heart to her contemplation of “Who am I? What next?”

That the picture’s brilliant final bit of dialogue, the best closing line in ages, lands so successfully is a testament to its star’s dexterity, effortlessly navigating the comedic and poignant. This comes as no surprise for those paying attention to the Australian, double Oscar nominee delivering diverse screen portraits across a string of pictures like I, Tonya, Mary Queen of Scots, Bombshell and last year’s unfairly maligned period Hollywood epic Babylon, which found her at her career best. Her Barbie comes very close.

Much has been written about the puppy dog-eyed Gosling stealing this very sparkling show, and his ebulliently clueless Ken gets a juicy arc, one where Gerwig allows him to sing, twice, tapping into his childhood toolkit from his stint next to Britney and Justin on The Mickey Mouse Club (or perhaps more recently, his impressive musicality in 2016’s La La Land). And although his sunny Ken is the in-spite-of-himself architect of Barbieland’s dark clouds, the beaming geniality and emotional comedy in Gosling’s work here is great fun in its pointed lampoon of male fragility. This is a big star turn, and one that should catapult the forty-two-year-old actor back to movie star status.

Gerwig, working commercially but infusing her third picture (after the acclaimed Ladybird and Little Women) with very real observations (suitable for adolescents and up) on gender inequity, female empowerment, the male ego and even the kind of world in which a progressive, modern woman might ultimately choose to live. She must be credited for an achievement antithetical to the modern blockbuster, foregoing the cynicism of Hollywood commercial manipulation to deliver a personal American movie about something genuinely important, and one that is going to sell better than probably any other this year. In 2023 she is the rare American filmmaker with something to say, and in Barbie, has found the perfect muse. And special mention goes to Helen Mirren, narrating the picture and getting a fourth-wall-break line that, like much of Barbie, brings down the house.

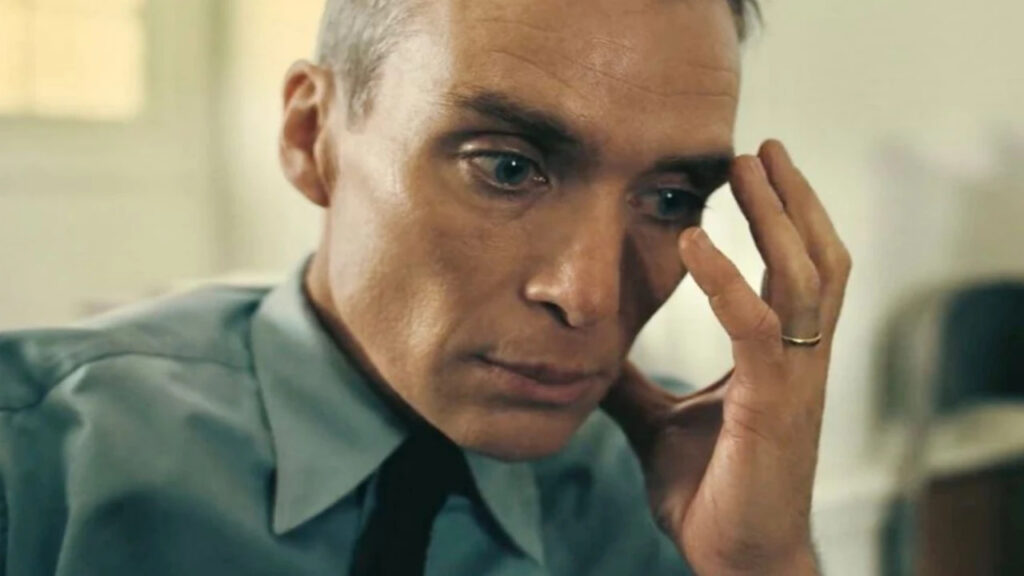

Also on this unlikely double bill is Christopher Nolan’s A-bomb opus Oppenheimer, a dense, often accomplished and sometimes portentous character study that both intrigues and alienates in its study of the birth of the Atomic Age and mastermind physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s (Cillian Murphy) WWII-era race to complete the world’s first nuclear weapon, after which he faces a personal and professional reckoning over his creation’s spoils. In telling this multilayered, ambitious story, Nolan has delivered an adult-level film that brims with ideas and signature command. Yet despite its weighty subject and obvious commitment and craft, Oppenheimer has curiously muted dramatic impact.

Based on the 2006 book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, Nolan has fashioned a multi-narrative, era hopping picture, a character study of the “father of the atomic bomb” with an excess of story agendas spanning from 1924 to 1963, crosscut for nearly the entirety of the picture’s 180-minute running time. As this is a Nolan film, byzantine structural puzzles are prized; humans not so much.

The fine Irish actor and Nolan regular Cillian Murphy plays the brilliant theoretical physicist, whom we meet early as frustrated Cambridge collegiate before going on to an academic career at Berkeley circa 1930s, during which he meets two very pivotal women, the passionate but mentally unbalanced Jean Tatlock (an underused Florence Pugh), with whom he has a years long affair, and the married Kitty (Emily Blunt), who gets pregnant, divorced and then unhappily married to Oppenheimer, a relationship Nolan undernourishes.

Enter The Manhattan Project, to which Oppenheimer is recruited by project director and Army Corps of Engineers officer Leslie Groves (Matt Damon). The nuclear race suddenly on, Nolan charts the advances of Oppenheimer’s extended team working diligently in their clandestine Los Alamos laboratory as a ticking clock competition against the Russians and Nazis. Such efforts culminate in the famous 1945 Trinity “Gadget” desert test plutonium detonation, which Nolan mounts sans CGI as a blinding flash of heat and light and cloud; the gripping technique is undeniably accomplished.

At about the two-hour point, Fat Man and Little Boy are infamously dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, effectively ending World War II (but ironically beginning the age of nuclear proliferation), and Nolan’s slavish adherence to Oppenheimer’s point of view means that the picture refuses to bear witness to the devastating fruits of his labors; Japanese destruction and its spoils are not depicted. It is a curious decision, and one wonders what Nolan might have done in emphasizing the bombs’ hellfire and its aftermath, surely bolstering Oppenheimer’s post-apocalyptic moral dilemma, a guilt that is vividly expressed in a superb, surreal sequence that finds the reluctant “American hero” speaking to an excited crowd of Manhattan Project teammates. This passage, with its nightmarish renderings ripped from Oppenheimer’s dark imaginings, is the picture’s bravura visual apex.

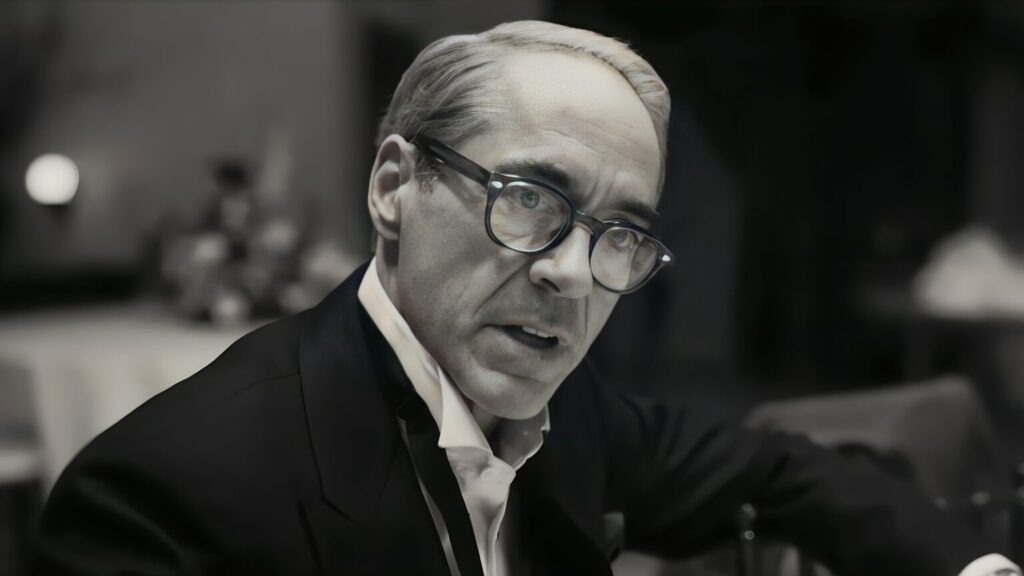

Nolan weaves in dozens of primary and peripheral characters, including a very good Robert Downey Jr. in a major dramatic return as U.S. Atomic Energy Commission chair Lewis Strauss of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, who recruits Oppenheimer as the program’s director before a humiliating public fallout. Nolan gives significant running time—too much—to Salieri-esque Strauss’ black-and-white shot, 1959 Senate confirmation hearings, providing a solid Alden Ehrenreich, as physicist Richard Feynman, with an effectively humorous interjection, while Rami Malek enters the picture for a brief testimonial, his role feeling truncated from a larger whole.

Yet another substantial section of the film deals with Oppenheimer’s 1954 security clearance hearing where efforts to revoke his access include Jason Clarke as special counsel to the Atomic Energy Commission, tasked with interrogating Oppenheimer, Kitty and a host of others in a claustrophobic, closed-door tribunal. This section, as well as the Senate confirmation hearings, are returned to over and over (and over) during the picture’s run time, woven together with the real-time Los Alamos bomb building and papered over with a far too-loud, too present score by Ludwig Göransson.

There is more, and more in this minimalist film dressed up as maximalist American history, including the fine David Dastmalchian in a brief but impactful role as William Borden, executive director of the U.S. Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, who raises suspicions that Oppenheimer just might be a communist security threat. Did I mention Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) turns up as Oppenheimer’s confidant and friend? Even Harry S. Truman (Gary Oldman, under makeup again) appears in a tense Oval Office meeting where Oppenheimer confesses post bombing that he has “blood on his hands” before the hardline president admonishes him a “crybaby scientist.”

By Nolan’s hand, J. Robert Oppenheimer is not just an American Prometheus but a Shakespearean figure—flawed, ambitious, isolated, plagued by internal conflict and ultimately betrayed—whose rise and fall as depicted here is political, historical, cultural and personal. Through these lenses there is history and substance here but the film itself is often detached and told largely as an overdetermined montage, liberally shuttling between multiple events and time frames, rarely allowing a scene to build or play out uninterrupted. Such rapid-fire editing tempers the already busy narrative’s impact. Still, while verbose and assembled to its dramatic detriment, in its best moments Oppenheimer manages to convey a shattering sonic boom of regret, courtesy of the haunted Murphy.

While Nolan has assembled a massive, high bar acting ensemble, both of his actresses are given dramatic short shrift, Pugh delivering her emotional, carnal all as the tormented Tatlock but hamstrung by a too-brief appearance. Similarly, Blunt is out of narrative focus for much of the film, mostly sidelined until a final reel interrogation ranking as perhaps the film’s most emotionally direct.

Film purist and preservationist Nolan, ever the cineaste whose pictures are shot on film and often in multiple aspect ratios most suitable for IMAX presentation, has as per usual struck 70mm prints for special theatrical exhibition. However, the pre-opening print I saw looked as if it had been running for a good few weeks, replete with dust and occasional scratches.

While Oppenheimer has a clarity of vision and technique to admire, Nolan has made one of his least engaging films. Intelligent, thorough, well-researched and acted, is also an arduous endurance test given the amount of talk in the picture’s first two hours, largely consisting of men in rooms debating science and not always in fully accessible terms. This makes the film sag in points, becoming the quintessential violation of the “show don’t tell” screen axiom; there is a lot of telling here.

Considering a career canon that includes such pictures as Memento, The Prestige, The Dark Knight, Interstellar, Dunkirk and Tenet, the extent to which each land on the audience is a Rorschach test for whether viewers have a stronger desire for the human experience, engagement and catharsis, or are happy to submit to Nolan’s cerebral, sometimes detached and often accomplished puzzles. Perhaps those familiar with the source material will have a deeper engagement to Nolan’s vision, but many will exit Oppenheimer wishing they had experienced a stronger connection to its people, rather than its filmmaker.

The end result of this impeccably mounted picture is one of something reaching for greatness but somewhat hindered by a heavy directorial hand—too much crosscutting, too much music, too many time frames at once and too little reflection until its final, strongest act. Sometimes a great story is a great story and can be told at face value, and the events of Oppenheimer’s story are epic enough that such directorial fussiness inadvertently diminishes them. No doubt this will be an unpopular opinion as much of the effusive critical discourse around Oppenheimer, currently awash in critical superlatives, suggests it a masterpiece. In truth, it is a challenging experience with middling returns.