By Francesco Bianchini

For the ‘in-between’ season, I liken the music of cello and piano, with cello representing wind stripping clinging leaves of oak and ash trees from darkened branches, swirling them through the damp air, and mounding them along the roadsides in viscous, bronzed carpets. The piano is the rain beating against windows, or down onto cobblestone paths and mossy roof tiles; sliding in heavy drops from drenched trees—not a sad melody, rather a reflective one, somewhat insistent, like a memory of autumns I can no longer place in time or space, yet that linger in my mind as a landscape of emotions.

Autumn sonata

This is what music does: it expands the boundaries of perception. It is not only the broad sodden fields, distant misty crests, or sheep under the rain, that I see from my window in the fading late afternoon light, but also a long-postponed departure, the sound of footsteps in the hallway, myself changing the bed sheets, after emptying the trash and putting away the folded laundry. The memory of a day perfect for dying, without leaving anything incomplete. Also the memory of objects left by someone whose face I struggle to remember; ordinary things—a black plastic watch, a pair of leather sandals—that stand as tokens of an absence, taking up space in a contracted world.

Our neighbours, the sheep

In a house whose sonority is amplified by its isolation in open countryside, one finds oneself inclined toward lengthy kitchen preparations. Not complicated dishes, but recipes requiring the laborious cleaning of ingredients, and slow cooking over a very low heat. Civet de lapin à l’ancienne, for instance, marinated in red wine (a Châteauneuf-du-Pape to be precise) and, helping to warm the large living room, simmered on the stove for an entire day in a magnificent Bordeaux-red enamelled cast iron cocotte—a precursor to the stew’s sanguine color, and its acidic, spicy aroma. Long considered a humble version of a hare-based dish, it is a preparation known since the days when wine was one way of preserving meat, mingling with blood, herbs—bay, thyme, rosemary—and spices like cloves and pepper. Or perhaps a leg of lamb cooked with turnips, carrots and fennel in a small, sky-blue cocotte en amoureux of such pure lines it could have been crafted by a raku-yaki artist. Or maybe one of our soups, ideal for warding off the first frosts: my minestrone—alas, missing black cabbage, but enriched with turnips and Jerusalem artichokes—and always better on the second day, or Dan’s all-American navy bean and ham hock concoction.

Civet de lapin à l’ancienne

Moving to the countryside can bring a slight euphoria at the notion, however dubious, of finding food simply by reaching out one’s hand. I’ve written before of our nettle feast from the wild meadow when we first installed ourselves in this quiet corner of the Lot, but in this rainy season, we’ve begun finding mushrooms of varied shapes and colors along the paths. In the case of mushrooms, great caution is warranted. In France, the expert to consult when in doubt is the pharmacist, who, as it happens, is also the mayor of our village. From the outset, he’d greeted us with a vaguely anxious look, as if our decision to settle on the margin of his district was a whim destined to pass; and at our entrance with a basket of mushrooms, he regards the suspect specimens we’ve brought with evident dismay.

After the rain

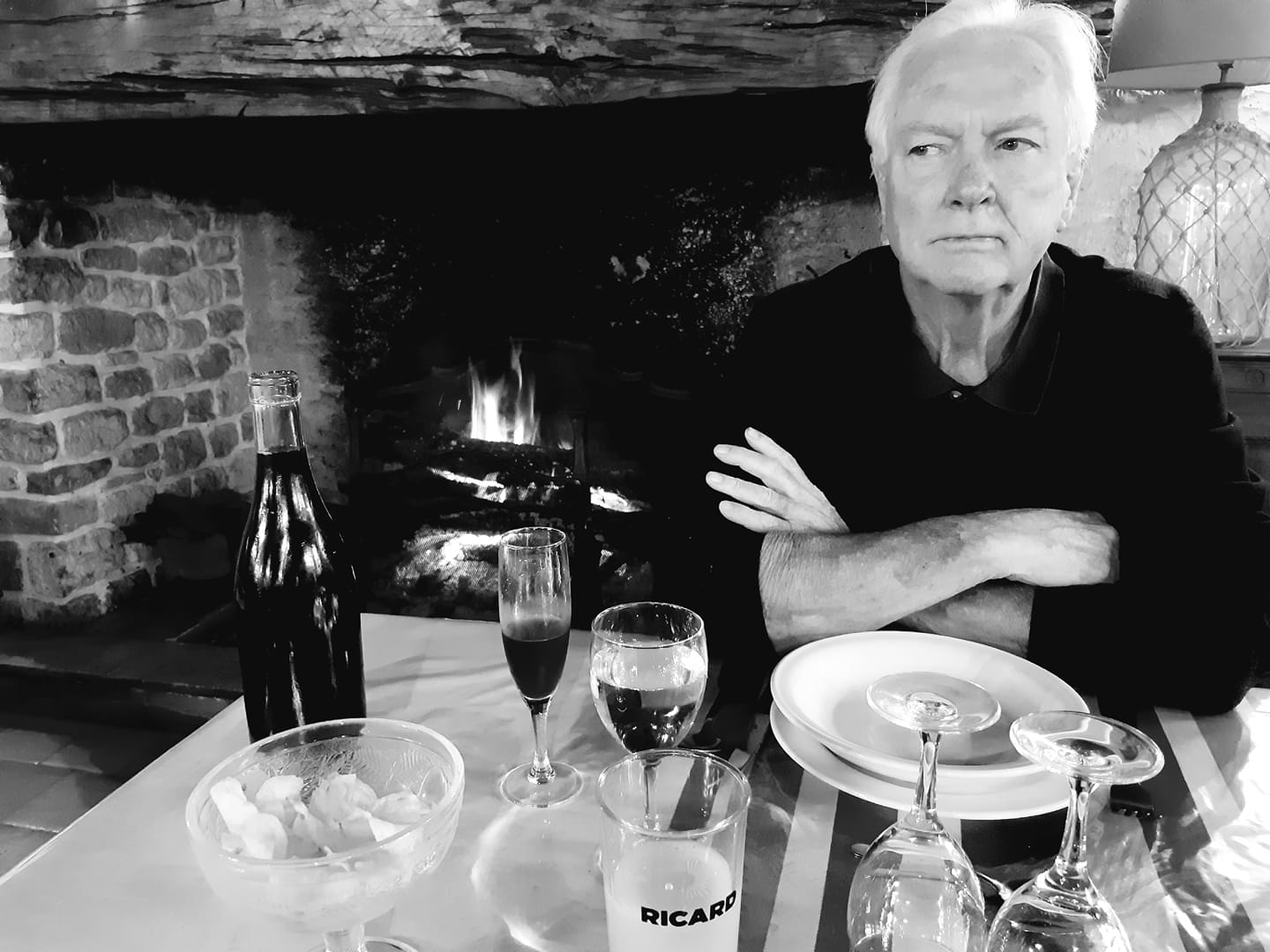

Certainly safer is frequenting the local eateries, open year-round and catering to workers and retirees. One nearby, called Chez Baillagou, offers a recurring menu that cultivates a loyal following; traditional Occitan dishes conceived to warm the body against winter’s chills: tête de veau with sauce gribiche or ravigote on Tuesday (a calf’s head cooked slowly in broth with greens and vegetables, served with mayonnaise made from boiled eggs and herbs); mique petit salé on Thursday, a cereal-based dish similar to bread, accompanied by salted pork stewed in broth. (A traditional dish of Limousin, Périgord, and Quercy, mique derives from the Occitan word mica, meaning crumb). And then there are coq au vin, pot-au-feu, or duck confit cassoulet on weekends. We are regulars now, with a reserved table in the stone-walled dining room, just in front of an ever-burning fireplace.

Across from our table, while we deliberate on the daily special, the waitress practices her dance steps, crossing her large feet in ballet flats. She isn’t young; she has more the look of an absent-minded aunt. No point in grilling her for the menu details, as she’s clearly here only to lend a hand—put to waiting tables to avoid causing trouble elsewhere—and has no idea what’s happening in the kitchen. She brings us our aperitifs: a walnut wine for Dan, and a pastis for me. The midday formula includes soup, ladled from plump, cream-colored crockery that circulates around the tables. By dipping the ladle to the bottom, the soup—a potage of vegetables or an Occitan tourin of garlic, onion, or tomato—retains the warmth of the pot where it simmered all morning. (The tourin of Périgord—garlic, goose or duck fat, flour, water, salt, pepper, egg, vinegar, bread, vermicelli—is often served to newlyweds in the early morning after their wedding day, celebrated for its hangover-healing virtues.) At Chez Baillagou we occasionally witness the long-forgotten rite of chabrol, recently revived: to the last spoonful of soup a splash of red wine is added, then drunk directly from the bowl.

Is she going to dance or serve the soup?

After the main course, there is always cheese—a Rocamadour chèvre made by one of our neighbors—followed by homemade desserts. A house specialty is their Norwegian omelette (that Americans call baked Alaska.) Auguste Escoffier was the first to give its recipe: vanilla ice cream placed on a sponge base saturated with liqueur, covered in meringue, and baked or flambéed until lightly charred. Its originality lies in the contrast between the frozen interior and the heated exterior. And it is this very contrast we savor all the more as winter’s grip tightens.

A fall feast awaiting our guests