By Daniel Strebin

Los Angeles area locals, and visiting tourists who were either savvy enough to seek out, or lucky enough to stumble upon The Chinese American Museum are in for an exceptional and rare historical and cultural treat. It is hosting an exceptionally thorough and illuminating tribute to the life of the groundbreaking Chinese-American actor, Anna May Wong, who battled stereotyping and prejudice to lead the way for future Asian Americans in pursuit of the Hollywood dream. Anna May Wong captivated audiences all over the world in the 1920s and ‘30s, appearing in more than 60 films, becoming the first international Chinese American movie star.

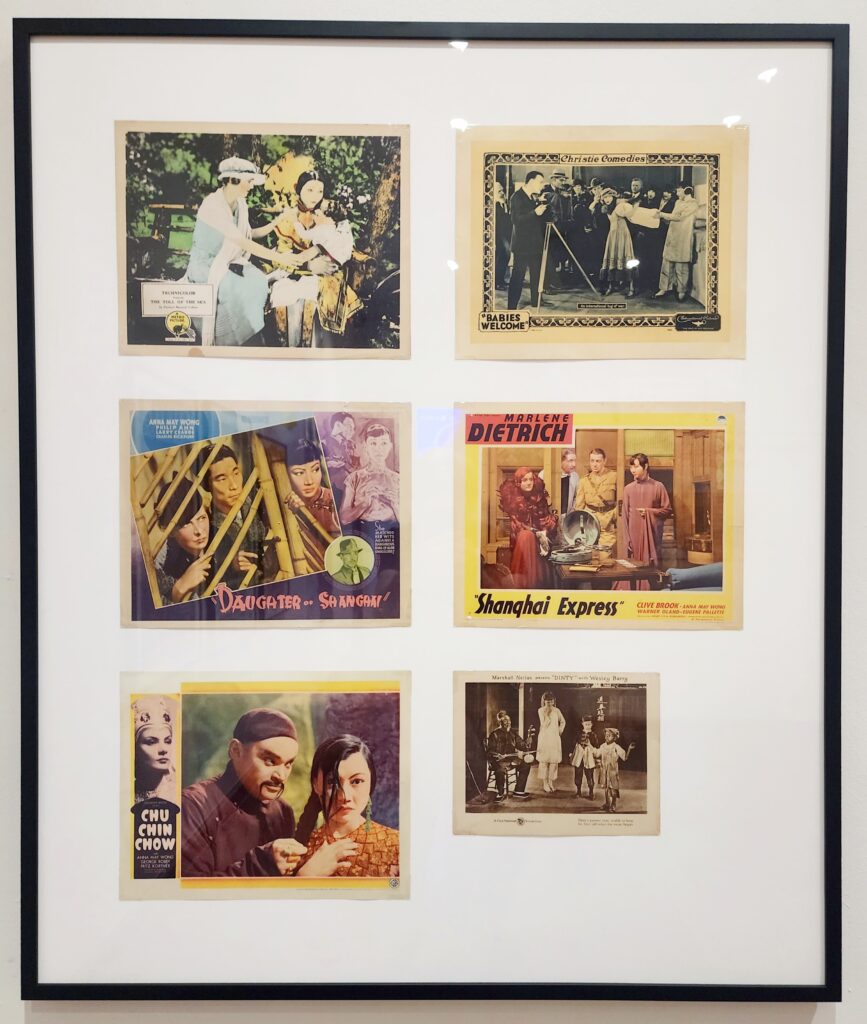

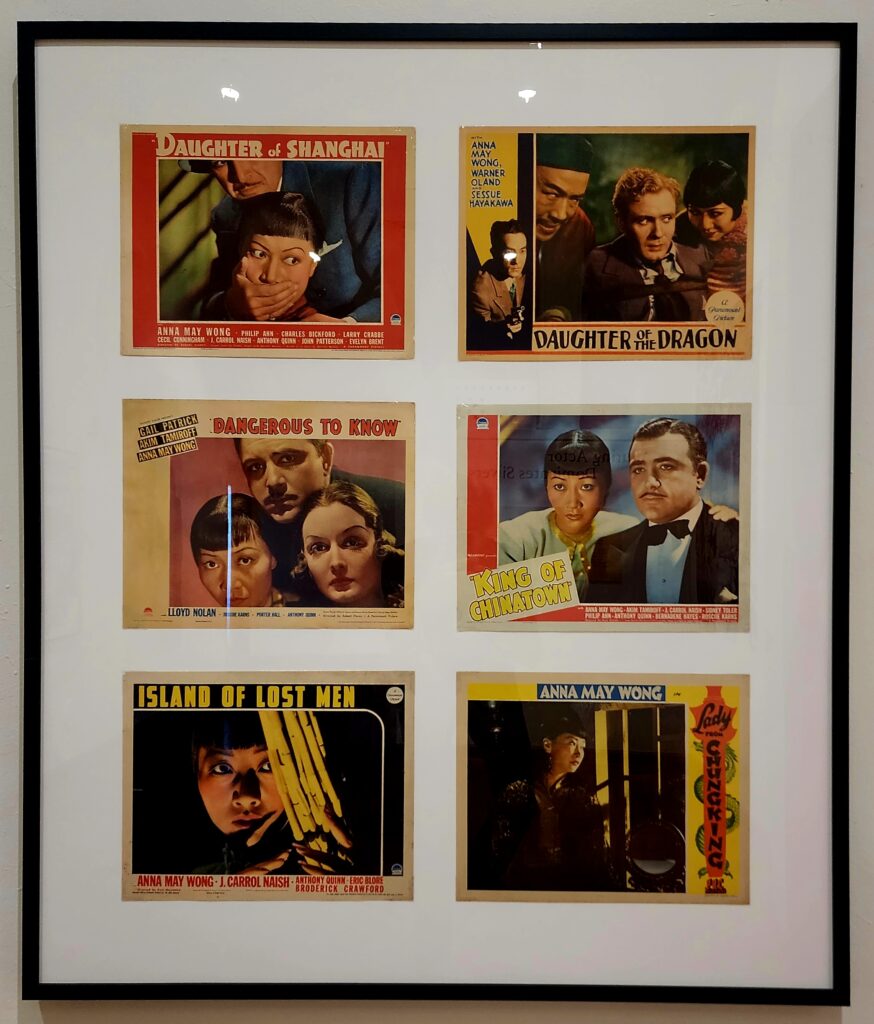

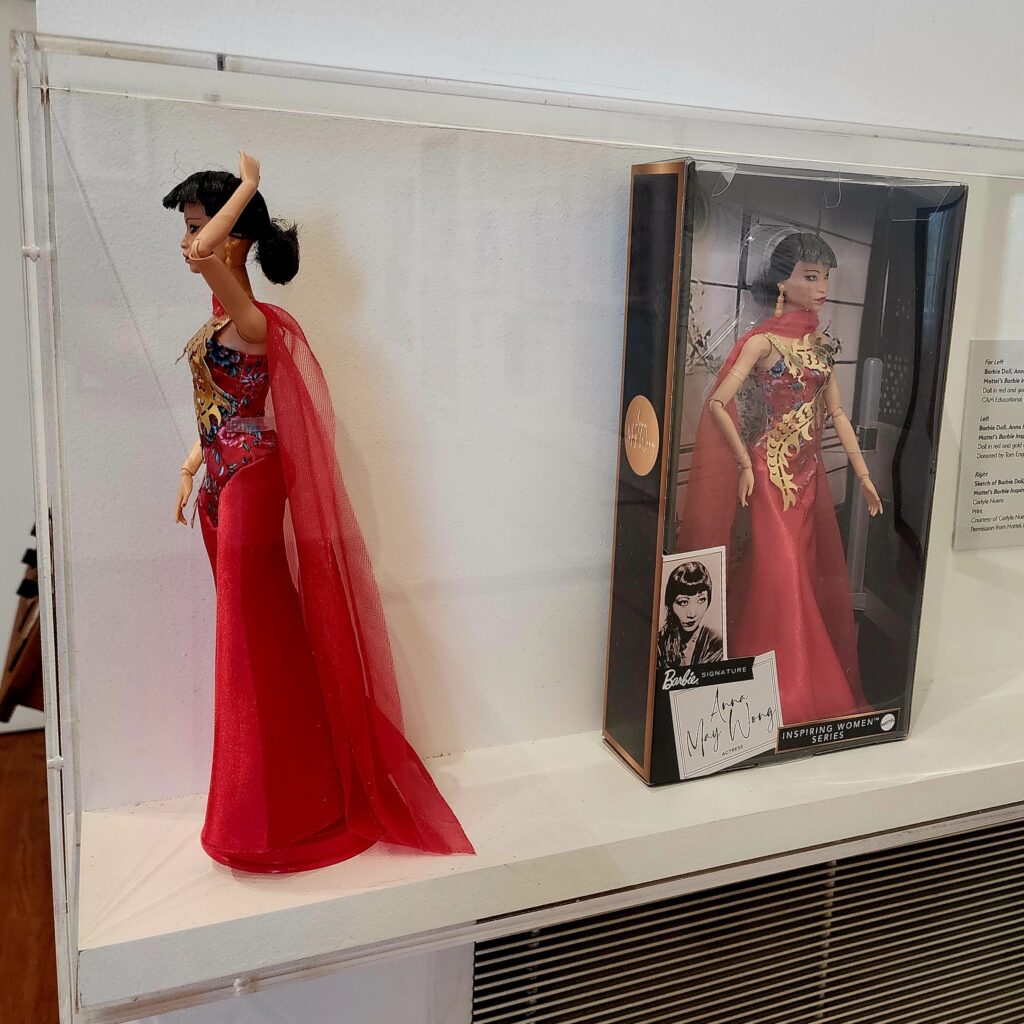

The exhibition, “Unmasking Anna May Wong” opened May 24 and continues through Jan. 25, 2025. On display are artifacts and memorabilia on loan, primarily from Wong’s descendant and namesake niece Anna Wong, and Chicagoan Dwight Cleveland, among others. A necklace and bracelets worn in the film Dangerous to Know, and loaned by Paramount Studios, is among the artifacts. Also on display are photos, rarely seen video clips, original lobby cards, posters, costumes, and a mural.

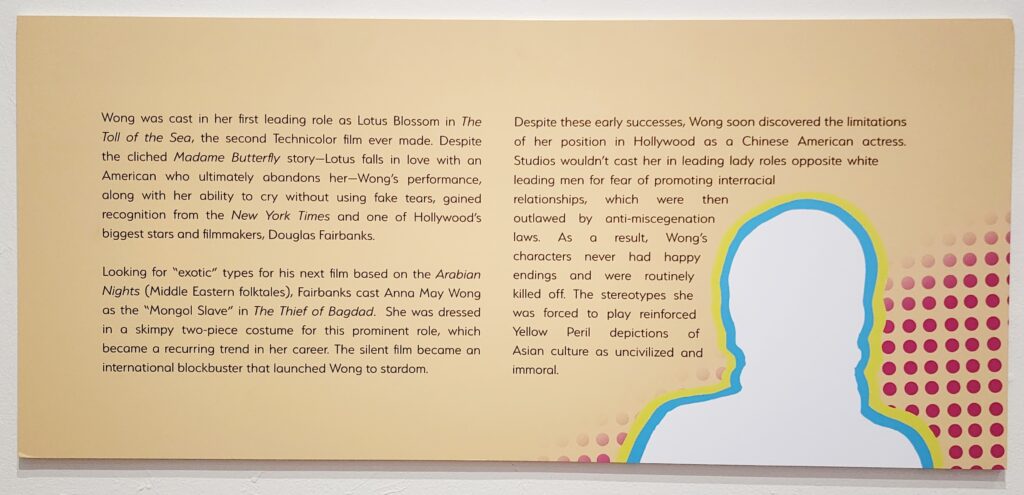

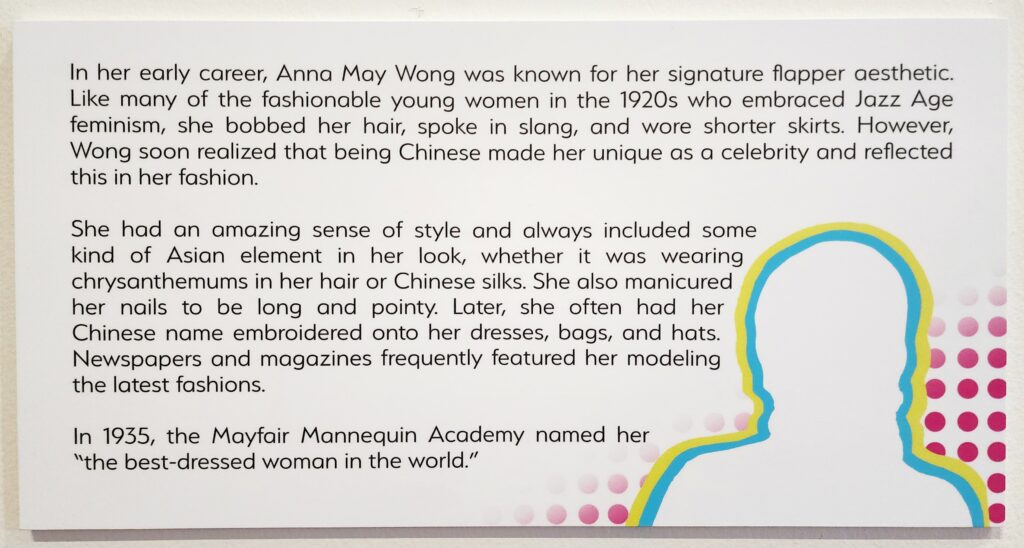

She was born Wong Liu Tsong in Los Angeles in 1905 to second-generation Taishanese Chinese Americans, her grandparents having arrived in California at the end of the 19th century, prior to the enactment of laws that restricted immigration from China to the United States. Wong starred in her first film in 1922 and, by 1924, had become an international star and fashion icon. Her career spanned silent films, sound films, television, stage, and radio. In 1934, she was hailed as the “world’s best dressed woman.”

Disillusioned by the stereotypical supporting roles offered, Wong started her own production company at the age of 19 to focus on Chinese stories and culture. In 1928, she took a break from the grind of the Hollywood studio grist mill, and in Europe starred in several notable plays and films, spending the first half of the 1930s traveling between the U.S. and Europe for film and stage work.

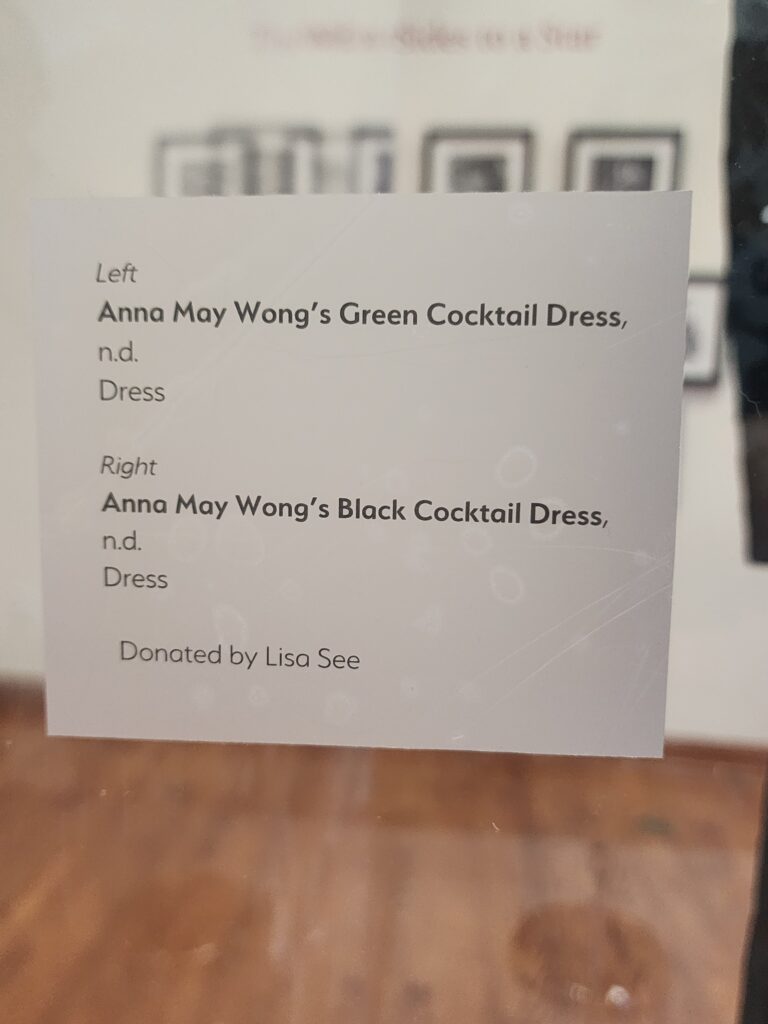

On exhibition are two of Wong’s dresses she wore that were provided to the museum by novelist Lisa See, and are among the most dramatic, personal, and indelible artifacts on display. Wong was often cited as one of the best dressed women in not only the country, but the world, a true fashion icon beyond national borders. In 1938, Look magazine named Wong the “World’s most beautiful Chinese girl.”

|

|

Personal Wardrobe

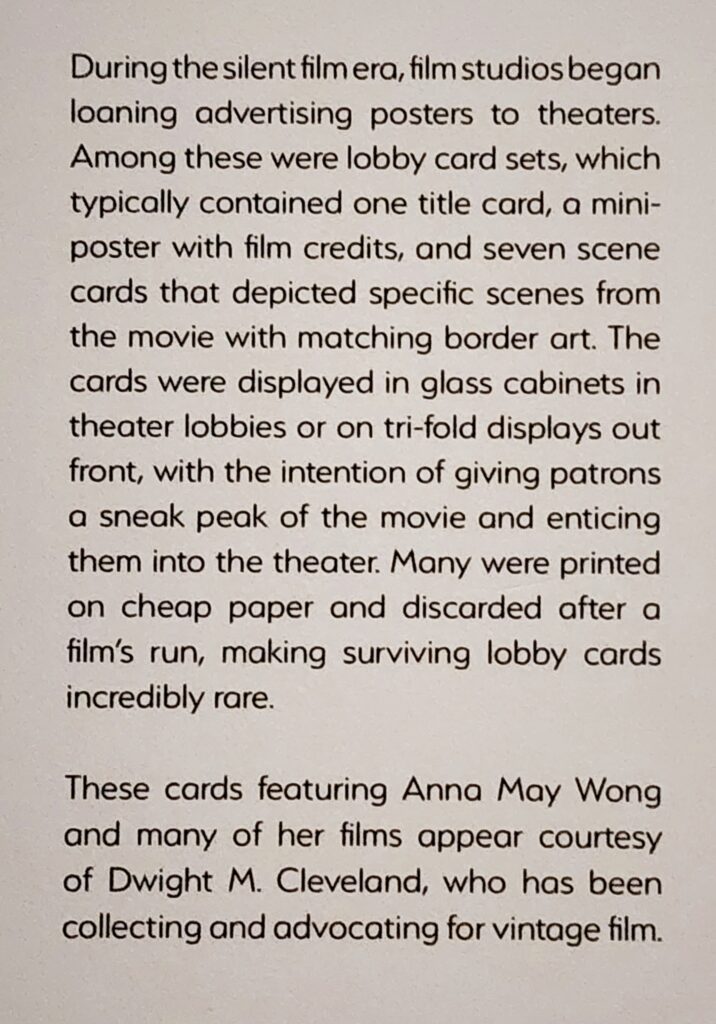

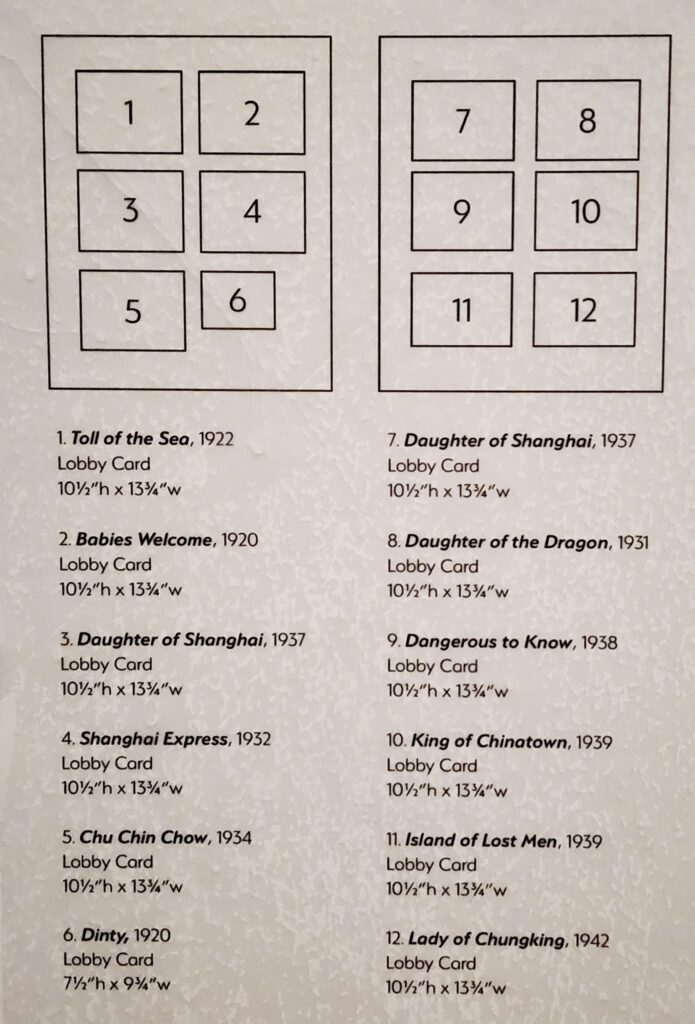

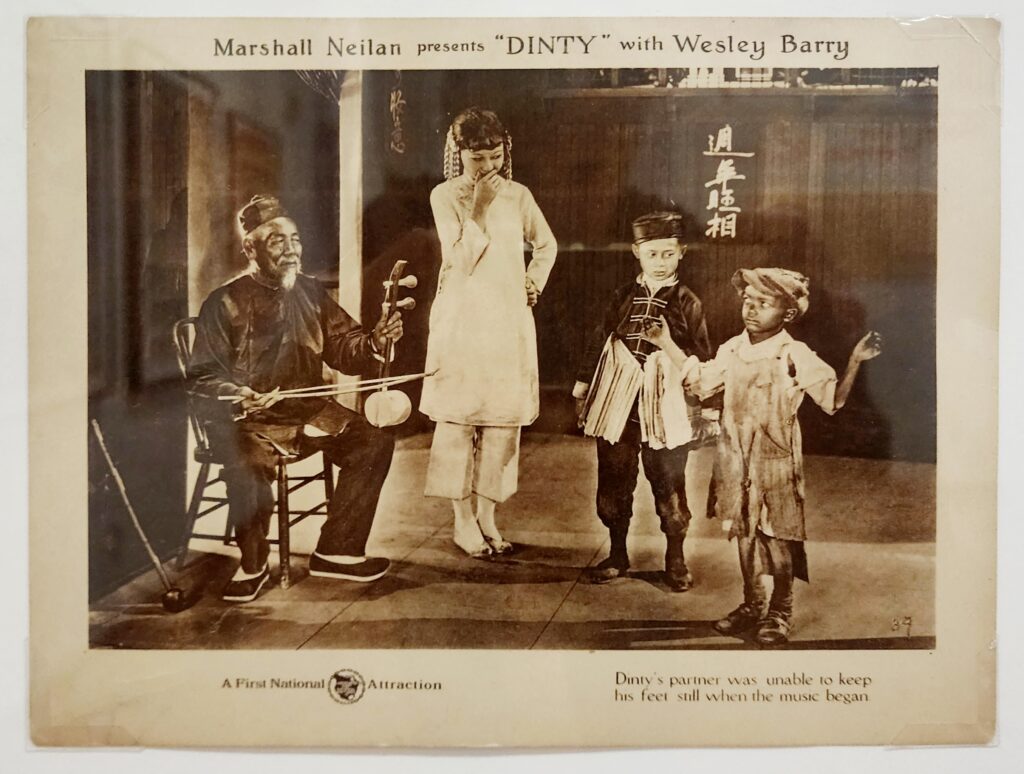

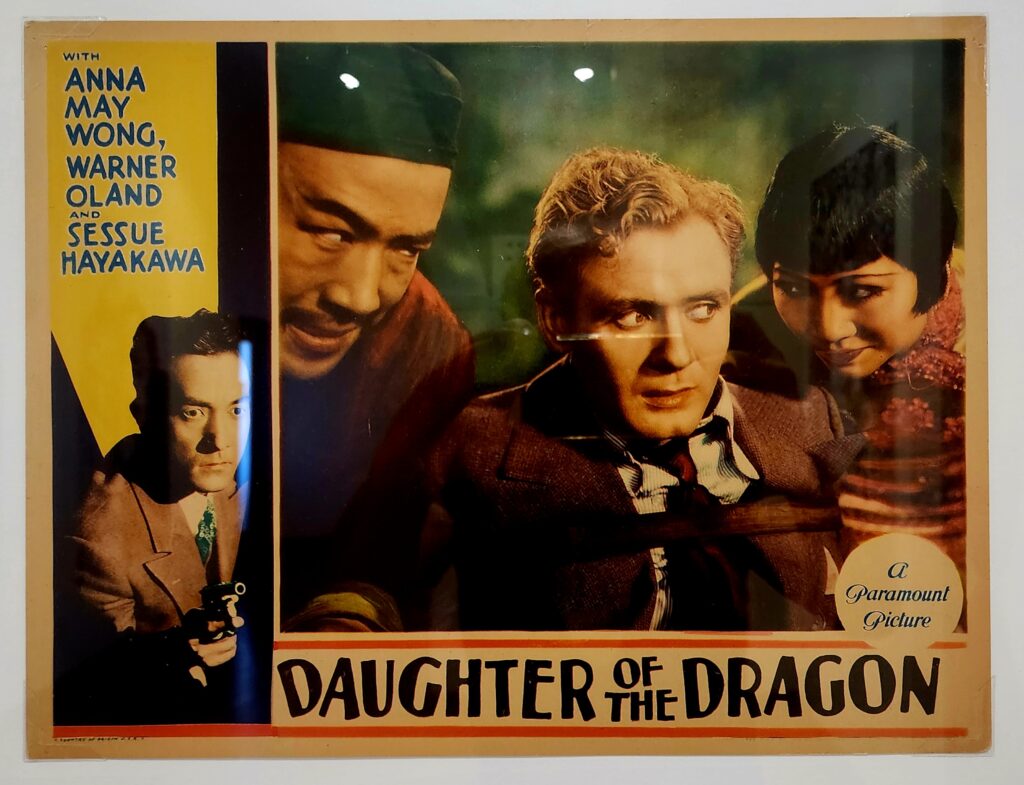

There is also a wall of twelve rare, beautiful original theatrical lobby cards (11″ x 14″ and 8″ x 10″) from her films during the 1920s and ‘30s. Included is her very first, the two-strip Technicolor film The Toll of the Sea (Metro, 1922), Daughter of the Dragon (Paramount, 1931) and a stunning scene card from Island of Lost Men (Paramount, 1939). On an adjacent wall are beautiful one-sheet (27″ x 41″) posters from Daughter of Shanghai (Paramount, 1937) and Dangerous to Know (Paramount, 1938).

|

|

Toll of the Sea

|

|

Poster Wall

These were graciously lent by Chicagoan, film art historian, and noted collector Dwight Cleveland, mentioned above. For the first exhibit ever of Wong’s film career, Cleveland loaned rare and precious movie posters and lobby cards featuring Wong to the San Diego Chinese Historical Museum. Those posters and lobby cards have now happily made their way north to the Chinese American Museum in Los Angeles. During his near half century collecting career, Dwight has made significant poster gifts to all the major film institutions around the world including a significant one to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences in 2013 which included many of his Anna May Wong 1-sheet posters. Dwight is also the largest donor of pre-1940 cinema memorbilia to The Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

|

|

|

|

In recent years, a groundswell resurgence in admiration for Anna May Wong has rightfully returned her to a deeply-deserved status as an icon of Chinese American culture. In her day, however, she often was cast in films merely as “exotic atmosphere” and would miss out on major roles, or even cause her trouble in China. When she played the supporting role of a prostitute in Shanghai Express, the Chinese government criticized her for playing a woman of ill repute. One Chinese newspaper’s headline read at the time: “Paramount Utilizes Anna May Wong to Produce Picture to Disgrace China.” But, remarkably, she was deeply interested in promoting China’s cause. When the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, she harshly criticized this act of aggression, and when Japan attacked the rest of China in 1937, Wong helped raise money for China’s war effort which soon became part of the larger global conflict as Japan allied itself with Nazi Germany, while America and Britain took China’s side in World War II.

While some conflict exists today with the Chinese government, informed and enlightened Americans have a heightened appreciation of the vast contributions of Chinese-Americans to our culture. In 2021, the United States Mint, as part of its American Women quarters series, depicted Wong on one side of a quarter, making Wong the first Asian-American to appear on an American coin.

|

|

Bianca Sparacino writes in her book A Gentle Reminder, “The kindest people are not born that way, they are made. They choose to soften where circumstance has tried to harden them, they choose to believe in goodness, because they have seen firsthand why compassion is so necessary. They have seen firsthand why tenderness is so important in this world.” After visiting the Chinese American Museum, you see what a kind person Anna May Wong was. She fought the daily battles, refusing to compromise, and giving of herself for others.

The Chinese American Museum is located at 425 No. Los Angeles Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012. Telephone 213 485-8567 or email: camla.org. Co-Curation by Katie Gee Salisbury, author of Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong and CAM Executive Director Michael Truong.

Photo Credit: Daniel Strebin