By Judy Carmack Bross

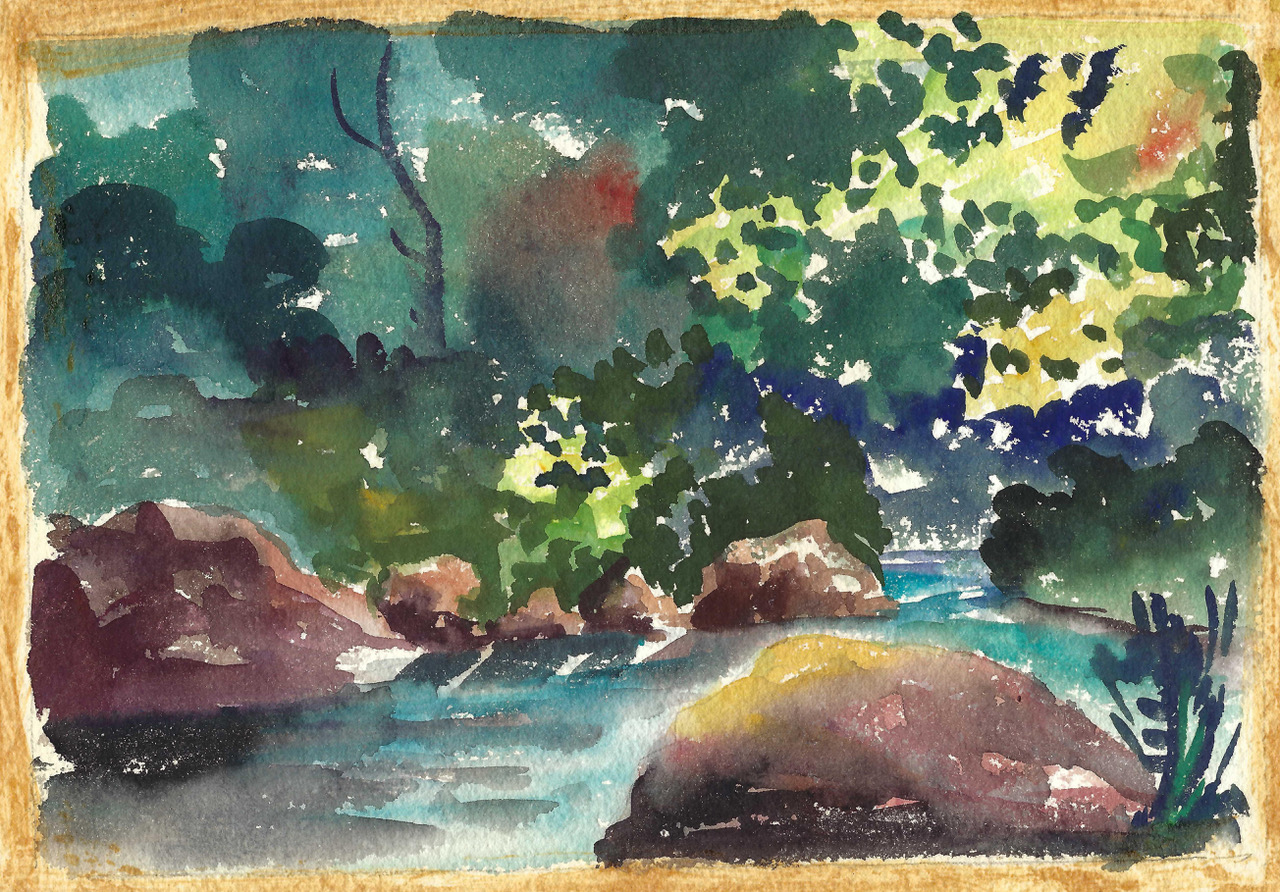

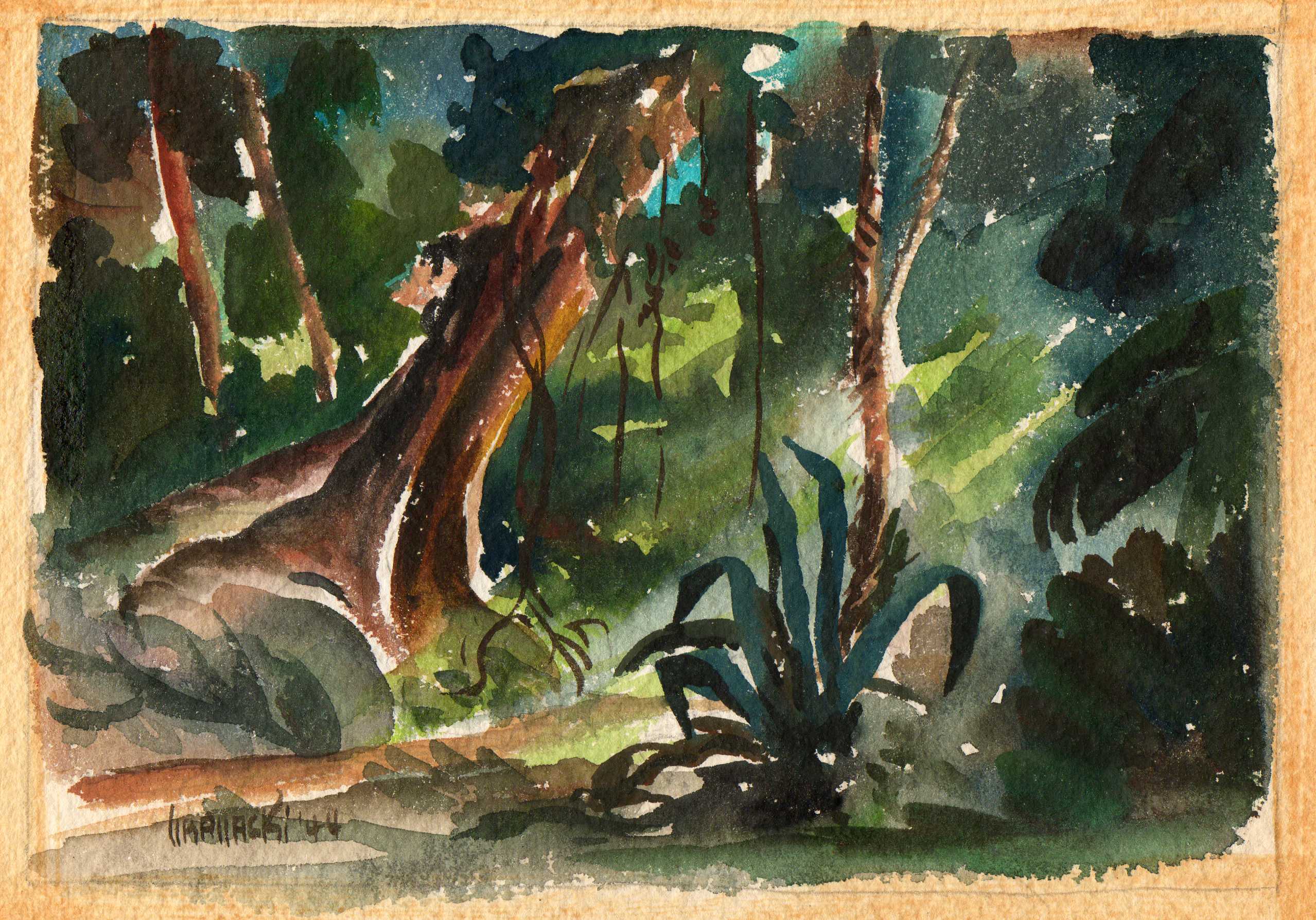

New Caledonia watercolor by Leon Granacki, 1942 |

Wisconsin watercolor by Leon Granacki, 1948 |

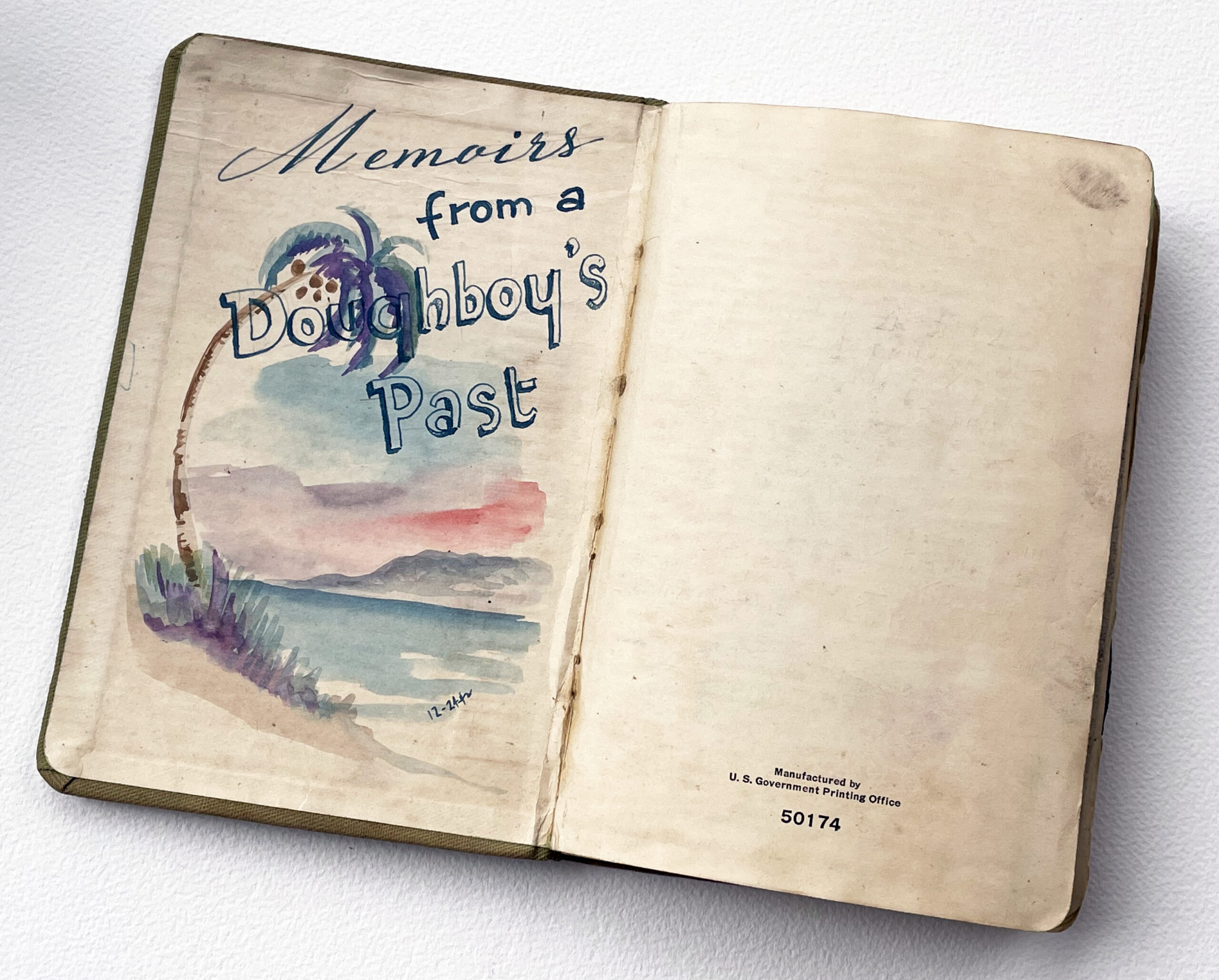

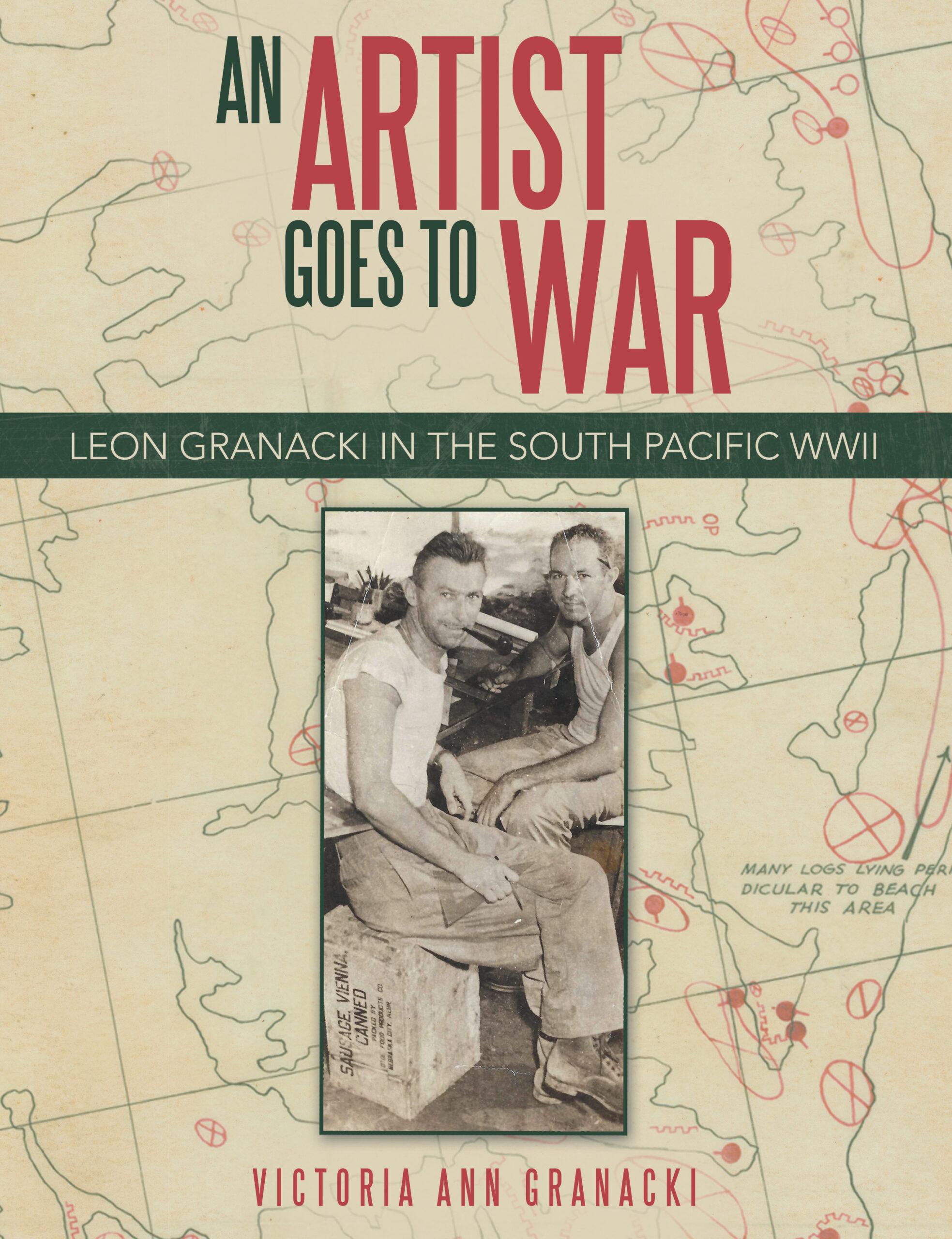

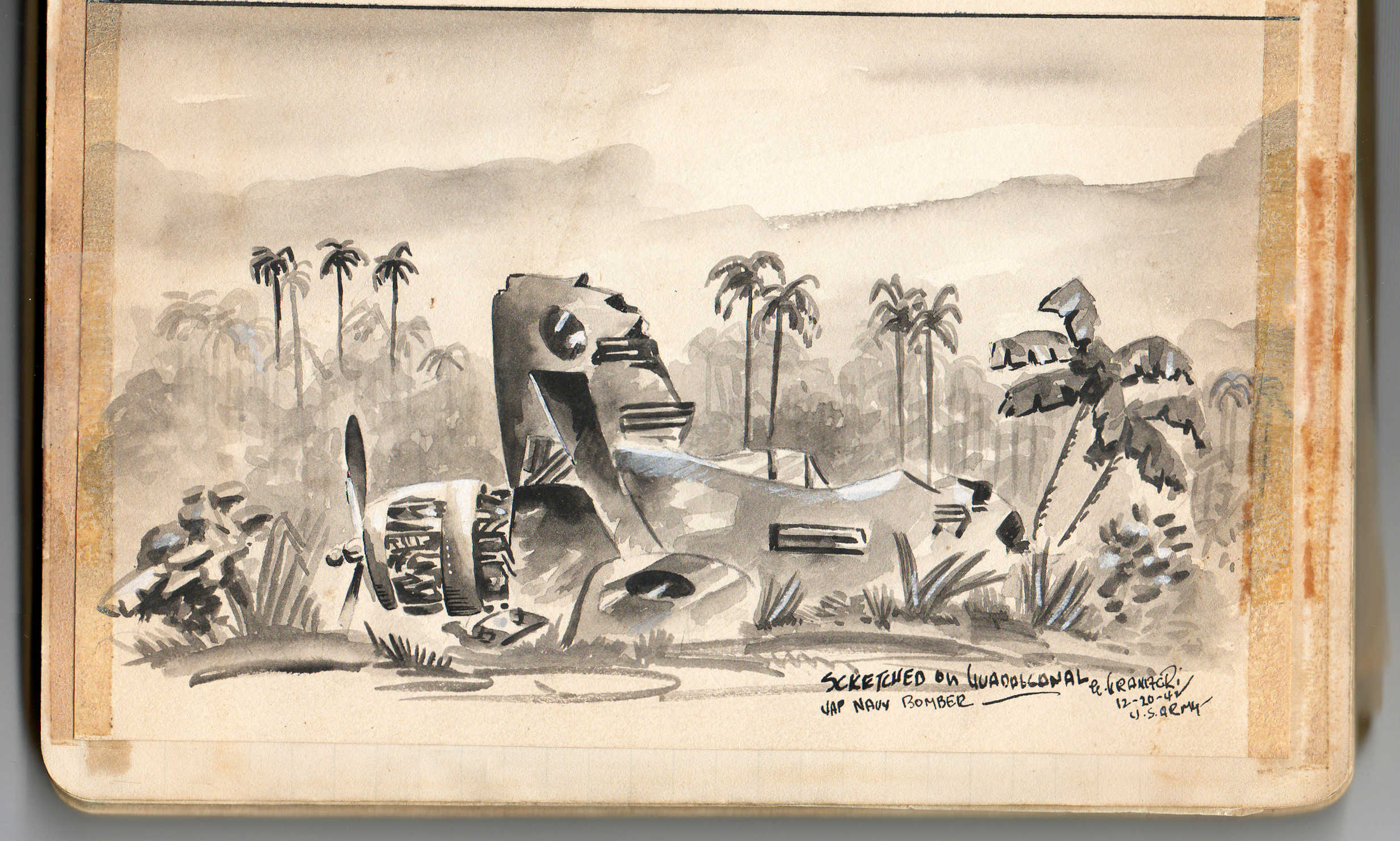

“My father died in 1993. The day after new tenants moved into his old flat, I got an excited call: ‘We have found something of your dad’s and I think you’ll want to see it right away.’ I made a mad dash to Keeler Avenue and as I burst in, they immediately handed me Most Secret: Memoirs of a Doughboy’s Past, the visual diary he began when he landed on Guadalcanal November 11, 1943. The precious little book had gotten shoved to the back end of the tallest shelf in my old bedroom closet. As I gingerly thumbed through the pages, I entered the life of my father the soldier—a life he had kept most secret from all of us.” –Victoria Granacki, author of An Artist Goes to War: Leon Granacki in the South Pacific WWII.

Cover of Granacki’s book about her father

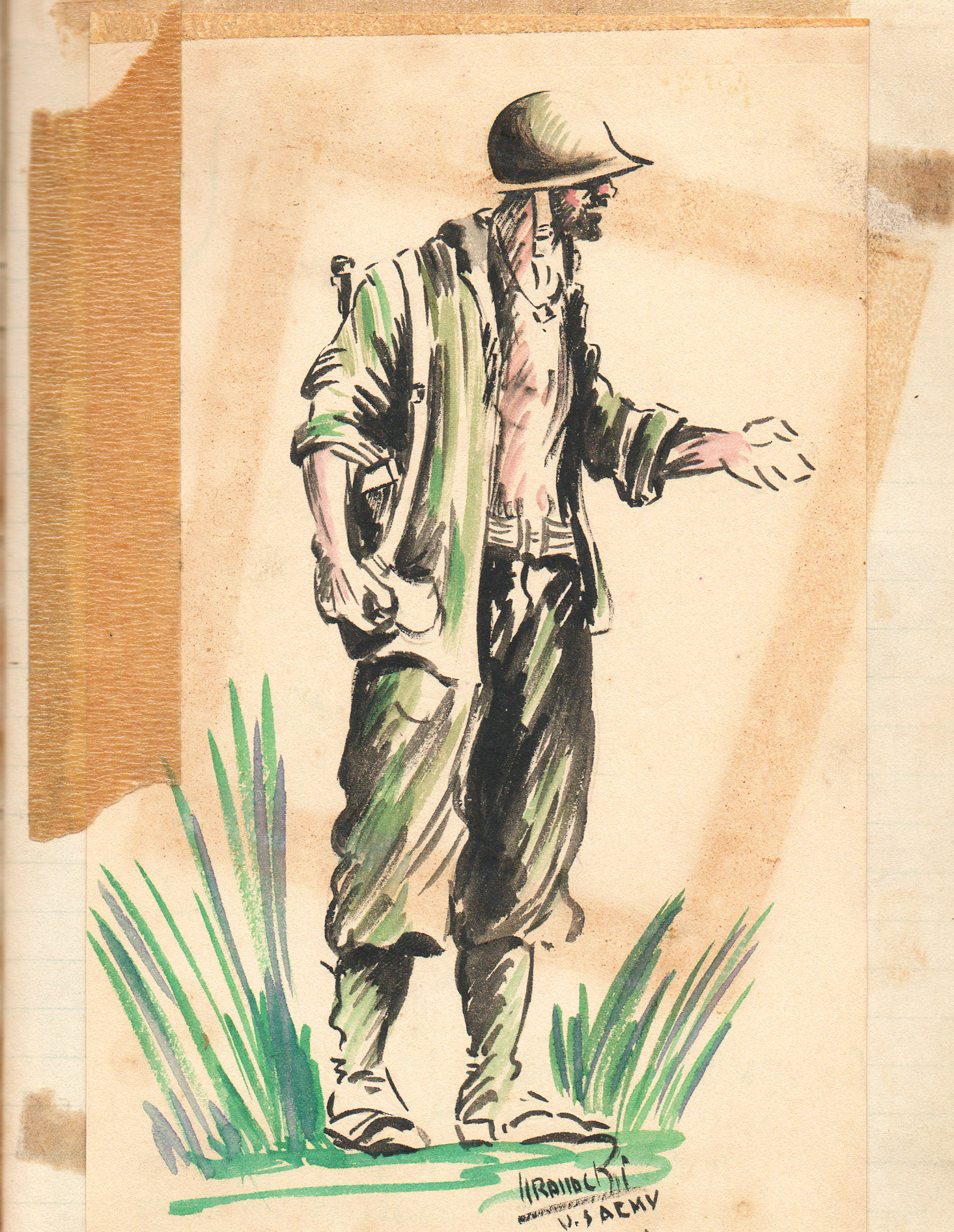

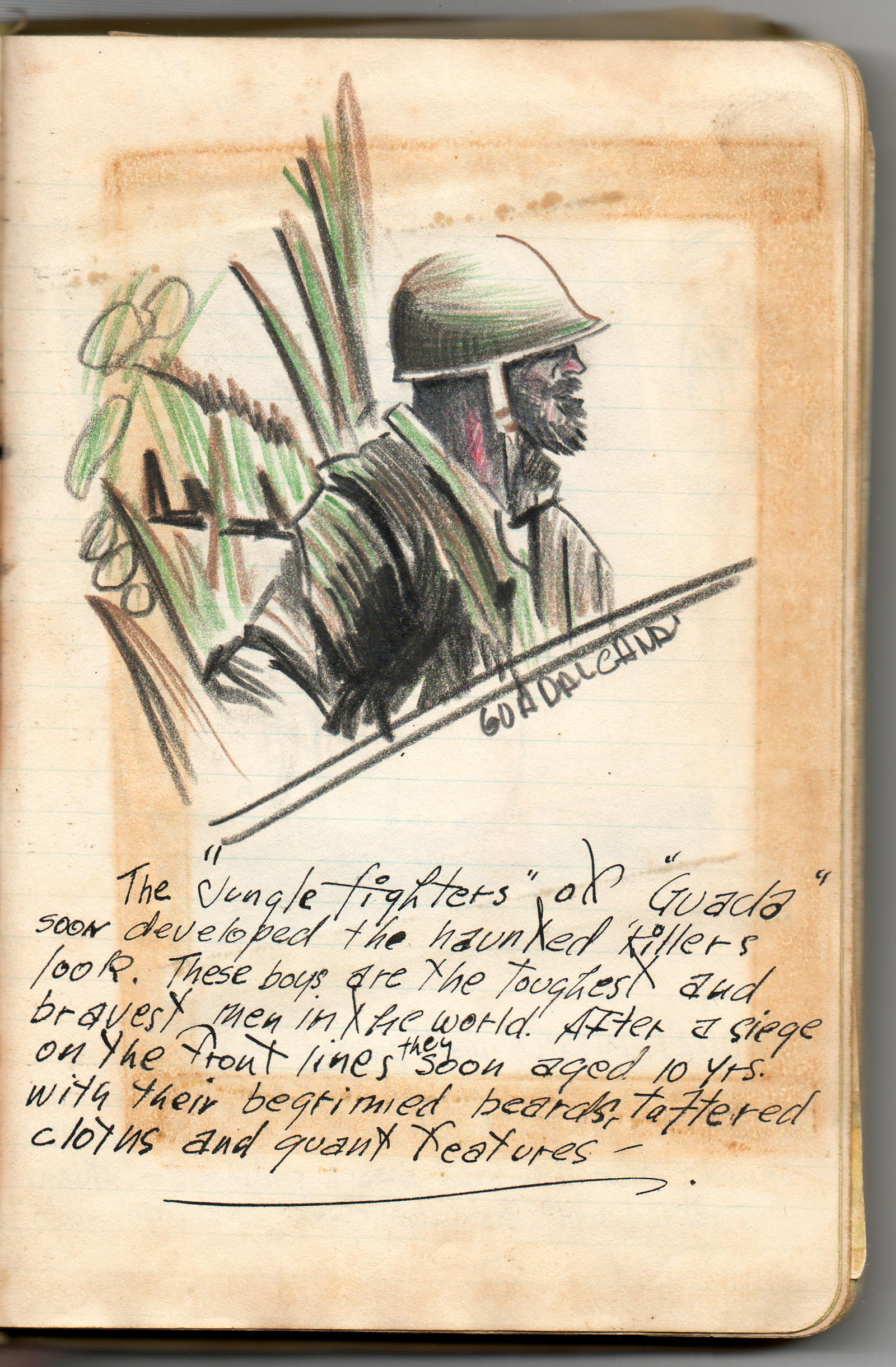

Jungle Fighter on Guada drawn in Leon Granacki’s memoir; “These boys are the toughest and bravest,” he captioned.

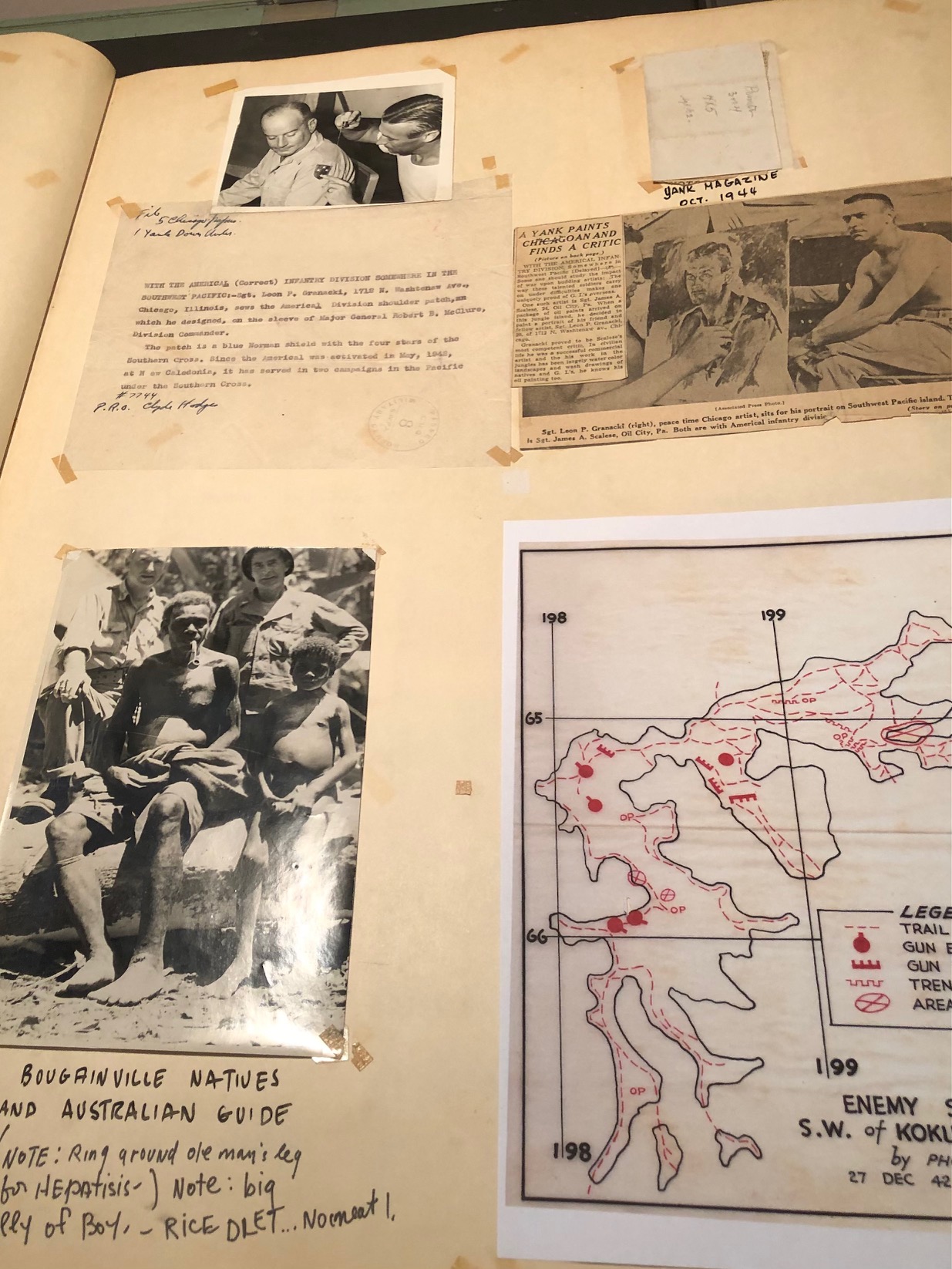

We visited with Vicki Granacki, who showed us her father’s diary, a large scrapbook with illustrations, maps that he had drawn for the army, newspaper clippings and photos, a binder of letters to his parents and many siblings put together by his sister Joy, his uniform, and much more. The discovery of the scrapbook in a storage cabinet in his studio in the basement of the family’s Keeler Avenue home was the catalyst for this book.

On Father’s Day we honor Leon Granacki and his daughter, who shares his story.

Young Victoria Granacki with her father, Leon

Granacki with her father’s uniform

Granacki scrapbook

Leon Granacki grew up on a farm in Pulaski, Wisconsin where Polish was his first language. They moved to Humboldt Park on the eve of the Great Depression. He entered Lane Tech, where he fell in love with art and studied drafting. Graduating in 1933, his cover for the Lane Tech Prep featured the World’s Fair. Looking for any work using his background, he took on odd jobs like sign painting and window displays and was hired by Petersen Furniture Company. One of six children, he lived in a 6-flat with parents, siblings, their spouses, nephews, and nieces.

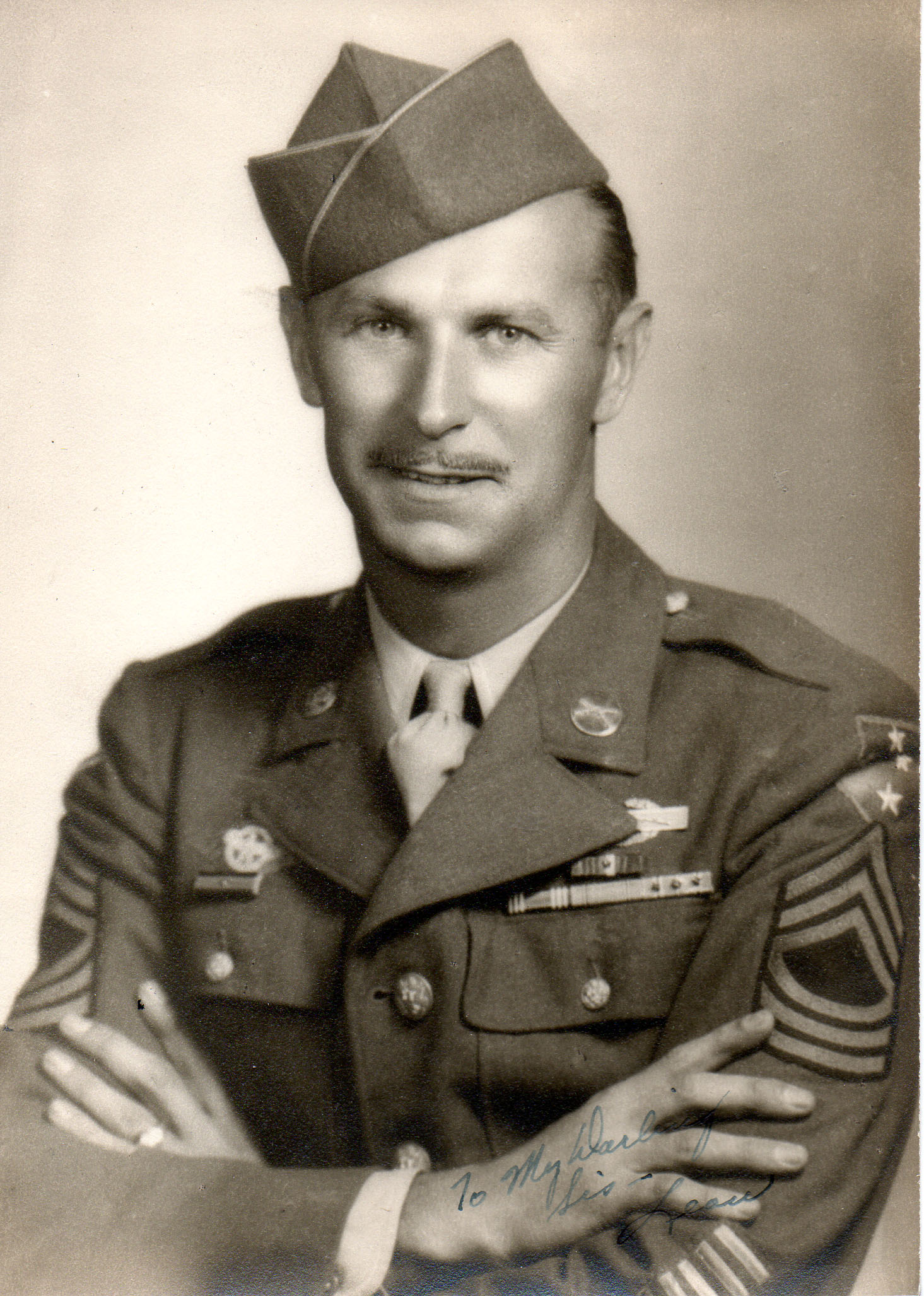

Portrait of Leon Granacki in his military uniform

“The SS Ranger transport ship in the South Pacific”

In 1941 he was drafted into the US Army 132nd Infantry and sent to Camp Forrest, Tennessee. After Pearl Harbor he was among the first troops to be shipped out to the South Pacific, landing in New Caledonia. In a military bio sheet, Granacki listed that he was a commercial artist. When he arrived an officer handed him a sheet of paper and asked him to draw the scenery off in the distance. The quick sketch so impressed the officer that Granacki was asked to join the Intelligence section and became the soldier who drew target maps from photos, including terrain information that was of great value in plotting battles. He was asked to design the patch for the Americal Division, which was named for Americans in New Caledonia.

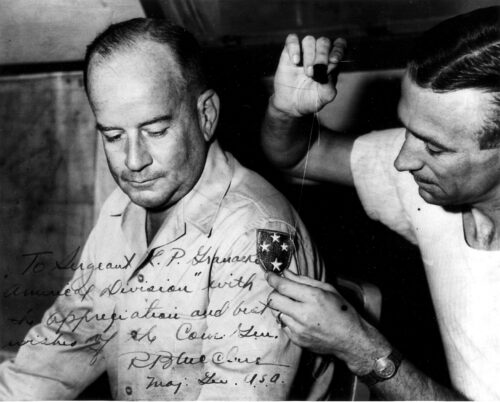

An Americal newsletter shows the photo with Granacki sewing on the patch he designed, and it described his career in the South Pacific:

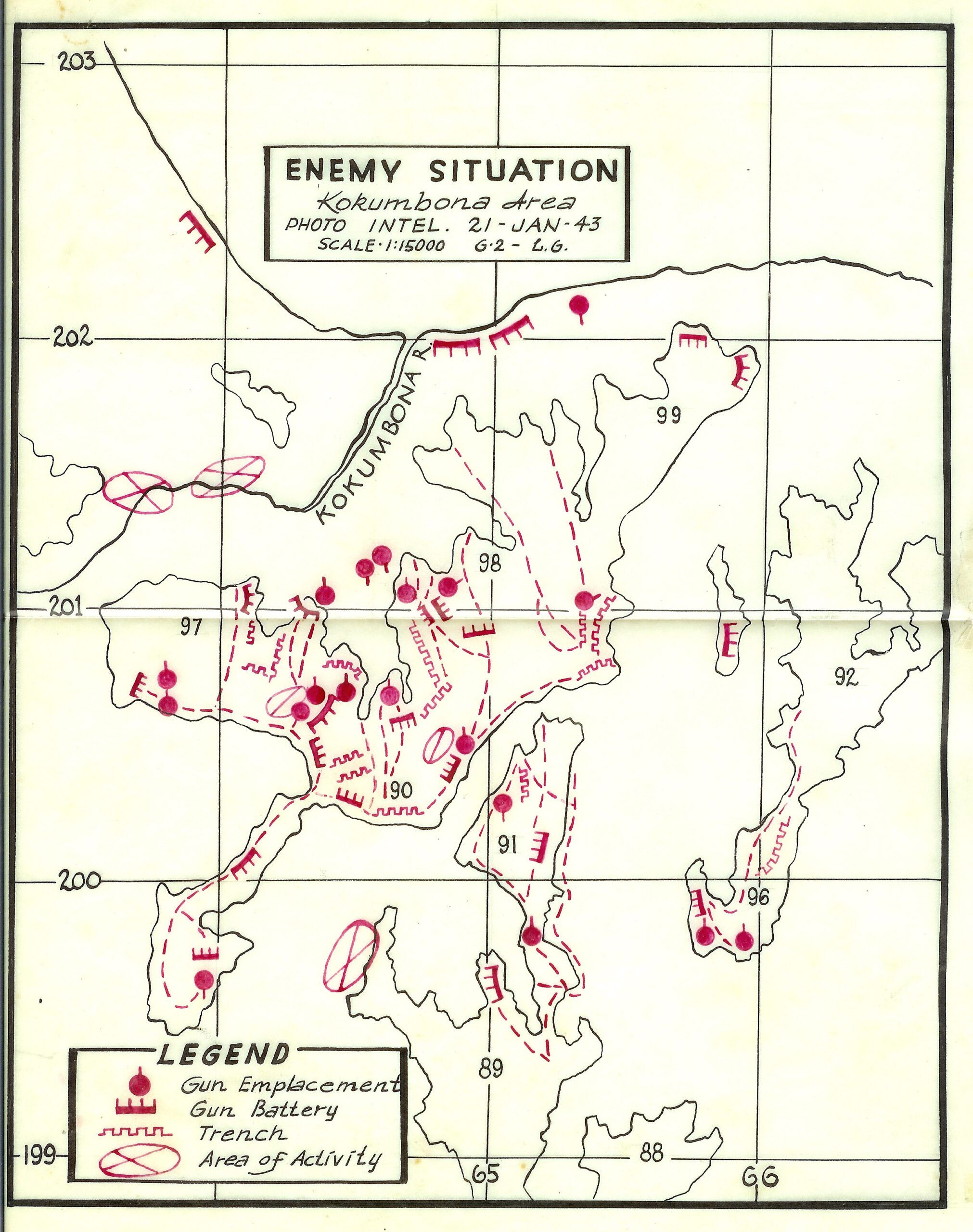

“Leon Granacki and his section used aerial photographs and captured Japanese documents to create maps which helped determine enemy positions for American battle plans. His outlines of coral reefs around Guadalcanal, the Philippines and other Pacific islands played a role in determining Japanese shipping lanes.

“During periods of relative calm, between island campaigns, he developed an expertise in watercolors and painted tropical scenes which in post-war years, were displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago.”

Leon Granacki sewing on the Americal Patch—“American Troops in New Caledonia.”

“When I was growing up I loved to go to his studio in the basement of our house. I remember two oil paintings of jungle scenes which hung side by side with watercolors of rural Wisconsin. He never talked about the war, which I think was typical of his generation. In the large scrapbook I found so many years later, there were watercolor sketches just like the jungle paintings that hung in his studio. The binder of letters my Aunt Joy kept usually began ‘Dear Folks’ and he always tried to be upbeat.”

“He was such an optimist and he didn’t want to scare them. He wrote that he wished he were home fishing with them in Wisconsin or how much better his mother’s cooking was compared with rations eaten out of a can. In only one letter to his brother Frankie he said ‘things are getting rough and I don’t know if I will make it.’ He described his map-making tent as his ‘Cactus Heights studio’ and, although he was spared from direct combat, he heard incessant gunfire in the distance,” Vicki Granacki said.

He spent much time on Guadalcanal and recorded Kokum Landing where he first landed

Major General John R. Hodge (left), Division Commander from May 29, 1943 to March 31, 1944, with Major Sergeant Leon P. Granacki

Rest Camp Fiji Islands

Granacki was discharged in June 1945 and returned to his job at Petersen’s after 4 years away. “They kept his job waiting for him during the war and sent him a money order gift every Christmas, as well as cards and mentions in their newsletter,” his daughter said.

He met his future wife Myrtle Meyer at Petersen’s, married in 1947, and moved to Chicago’s Old Irving Park neighborhood. They had two sons as well as a daughter, Vicki. When Petersen’s closed, he did newspaper advertising design for Polk Brothers.

“He had such a great sense of history and this history is still preserved for us 80 years later,” Vicki said. “Our whole family saves things and what they saved here is an important legacy. Writing this book, filling it with his art and letters and souvenirs, has been my responsibility.”

Granacki still owns the family home and writes at the end of her tribute:

“Even though the three flats on Keeler are fully rehabbed and rented now, I haven’t changed his old studio. I can still handle his artist tools and imagine how his own hands held them—his fingers flexible and his wrists swaying when he was young, and then as he got older, his hand still and twisted with arthritis, yet each stroke still perfectly controlled. I can feel his spirit when I stand where he stood and hold the old drawing tools he held—his energy is in them, his life’s love, his art, his service.

“I can try, however weakly, to understand his life—how an artist became a soldier, and then a soldier became an artist again and forever.”