By Elizabeth Dunlop Richter

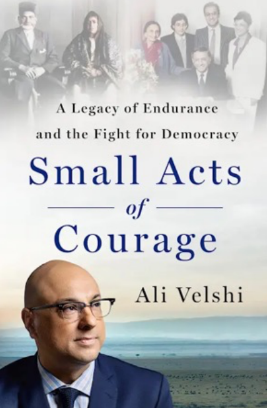

From jumping into shark invested waters in the Indian Ocean to moving to four new countries on three continents, Ali Velshi’s ancestors were resilient and determined to do what was necessary to find freedom in a world unwelcoming to their brown skin. MSNBC anchor and senior correspondent Ali Velshi wraps his family’s fascinating history around a passionate plea to take responsibility for preserving democracy in his new book, “Small Acts of Courage.”

Holding more passports than most of us can imagine (four), Velshi is immersed today in American politics and now an American citizen: his background reflects a family traveling the world to find a place that would welcome them, offer opportunity and to which they could contribute. His family story goes back 125 years to a small town in India and ends with a special connection to Chicago.

In 19th century India, Velshi’s great, great grandfather Keshavjee Ramji Murhi was a successful businessman in the town of Chotila in the Indian province of Gujarat. India was then under control of the British Raj; a combination of oppressive colonial regulation and devastating droughts and later famine throughout the country forced a massive Indian diaspora. Africa offered some of the best alternatives. By the end of the century, Keshavjee Ramji Murhi’s son Jivan decided to emigrate to South Africa where he was able to establish a new business, soon joined by his brothers including Velshi’s great-grandfather Velshi Keshavjee (his given name would eventually become Ali’s surname).

The Boer War forced many Indians to leave South Africa. In 1901, Velshi Keshavjee, having gone back to India for the duration of the war, set out to return to South Africa. When his ship crossed the Indian Ocean and docked, an apparent stolen identity prevented his disembarking. “Small Acts of Courage” describes what happened next:

“His first, best, and possibly only chance to making it to Pretoria was to dive in and swim for it. So that’s what he did. He climbed on the rail of the ship, said a prayer, lept into the choppy shark-infested waters below, and swam for his life.”

Velshi’s great-grandfather was a strong swimmer and rejoined his brother in the Indian ghetto outside Pretoria, Marabastad. Certainly an act of courage, but also a significant step in the Brothers Keshavjee’s settlement in South Africa, leaving their own country for new opportunities. South Africa, however, would not be the family’s final destination.

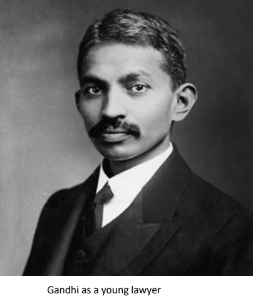

Indians emigrated to South Africa initially as indentured laborers and later as “Passenger Indians” like Velshi’s ancestors, who paid their own way to establish businesses to serve the ever-increasing Indian population. “Small Acts of Courage” details the complex 19th century history of the English, Dutch Boer, Black native, and Indian interactions (or lack thereof!). Indians were treated as second class citizens, a step below the ruling white government. These conditions inspired a young British trained lawyer also from Gujarat, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, to work on behalf of exploited Indian laborers. In Pretoria, he befriended Velshi’s great-grandfather Velshi, also from Gujarat.

Reacting to the 1906 establishment of the Union of South Africa, Gandhi would develop in Ali Velshi’s words “a moral vision that spoke to the need for dignity and self determination for all humanity.” (“Small Acts of Courage”). Later called “satyagraha,” the evolving movement stood for truth, love and non-violence. The Keshavjee family was not initially engaged in the movement outside a continuing friendship with Gandhi, but soon would. To build an educated following Gandhi built an ashram called Tolstoy Farm. Gandhi urged by his friend Velshi to enroll his son Rajabali, age seven. “Tolstoy Farm trained and equipped my grandfather in the same way a paramilitary camp might train a young revolutionary soldier, only it trained him for an entirely different kind of war, arming him with self-discipline and self-reliance instead of hand grenades and a rifle.” (“Small Acts of Courage”).

Rajabali would remain in South Africa and run a successful bakery business supported by the discipline and philosophy of the Tolstoy School and continue to serve his community. He defied local custom by selling half-loaves to native Blacks so they could afford bread. After World War II, the National Party gained power and established the brutal apartheid system that would totally control and impact the bakery business, down to the amount of yeast allowed. Rajabali’s brother Rehmtulla a well-known anti-apartheid activist, attracted suspicion to the family and the bakery business. By the 1950’s, it was clear that it was impossible to remain. Once again the family would have to move. Ali Velshi’s grandfather died of a heart attack shortly after, in tears he watched the demolition of the 70 year-old bakery. Velshi’s father Murad and mother Mila left for Nairobi, Kenya, also a British colony, to join a brother in hopes of finding freedom at last.

Ali Velshi was born in Nairobi where his Uncle Habib ran a successful dry-cleaning business, despite being a supporter of Kenyatta and the violent Kenyan independence movement. With independence, Kenya did well economically and politically but over the years, the Africanization in Commerce and Industry law and Kenyatta’s lack of commitment to pluralism made life for Indians more limited. Finally warned to leave the country by political friends, Velshi’s family left for Canada when he was just a year old. The journey continued.

Velshi enjoyed a carefree childhood in Toronto. His family was finally welcome. Canada would in 1971 put into law the family’s experience. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government legislated “multiculturalism” as a national policy, designed to encourage ethnic groups to maintain their languages and cultural freedom while enjoying the benefits of a Canadian lifestyle. Canada made a dramatic effort to welcome immigrants, streaming in initially from Uganda, then under the control of Idi Amin. The civic-minded Ismaili Muslim population, of which Velshi’s family was a part, set up a major financial system to support South Asian and African immigrants.

“When one group is closed off and defensive and bigoted, the other group feels it has no choice but to be closed off and defensive and bigoted in return. In Canada, however, instead of fighting all this nonwhite, non-Christian immigration, they actively welcomed it…the difference in results could not be starker.” (“Small Acts of Courage”).

Velshi recounts one his most vivid childhood memories… and lessons: his father’s campaign for political office. At age 11, Velshi was old enough to help his father with his first political campaign, for a seat in the provincial parliament. There were no “brown” elected office holders, and his father Murad Velshi, always very active in the community, decided to step up. Young Ali went door to door with his father and talked to voters. He loved it. The election results came when he was riding home with his dad election night at 8:01 (polls closed at 8). His father’s loss was called immediately, the only race called so early. “I was shocked… I can’t believe we lost, I said…of course we lost, [his father] said with the biggest smile. ‘We were never going to win…We ran because we could’….That was the night I learned that there is a deeper way to think about politics…when I hear people run down politics and politicians, I recoil. Because cynicism about politics is actually a luxury of those who have never had to experience life without it.” (“Small Acts of Courage”).

Murad Velshi ran again, this time successfully in 1987. His son was much more involved now at 17. “It was a seminal moment for immigrants in their civic and democratic experience in Toronto.” (“Small Acts of Courage”)

Despite his love of politics, Velshi did not pursue it as a participant. He studied religion at Canada’s Queen’s University (from which he would later receive an honorary doctorate), discovering his ability to write and tell stories He shifted into journalism and after graduation moved from local news to national financial reporting. His first day in the US to work for CNN, he drove over the George Washington bridge on his motorcycle two days after the destruction of the twin towers.

‘I arrived in the shadow of 9/11…that was something else…” he told me. “One of the downsides of 9/11 is immigration is now seen in America as a security matter… It backs up the impression that some people have that immigration is a negative, that is a risk to the country. We have to start thinking about that very differently…We have to start thinking of immigration in part as a labor imperative, in part as a societal and population imperative, and in part we have to get away from the concept that it’s charity… Fundamentally we need these people…we just have to decide to have the will to do this.”

Velshi’s approach to journalism links him to Chicago in a special way. He’s a trustee at the Chicago History Museum. I asked him how that happened. “Coming from Toronto, there’s a natural affinity with Chicago. It’s the American city most like Toronto…I look for any excuse to go to Chicago, and on one of my visits I went to the Chicago History Museum.” Velshi decided he wanted to get involved.

Gary Johnson, president of the museum at the time, recalls, “I got a call [from a mutual friend in the financial world] that Ali wanted to meet me. That sounded like a good idea; we met for coffee, and it was one of the most remarkable introductions of my life! He’s a museum guy.” Johnson learned that Velshi visits museums when he’s on the road. “It seemed to him we were doing what he wanted to do as a journalist. Of all the museums he’d seen, we were doing the best job. That was a wonderful introduction,” said Johnson.

“[The museum] connected to me as a journalist,” said Velshi. “The exercise is curation…you go and you go and you go again and you trust the curator. I think about the news that way. We are curators you have to trust that I’m not giving you all the news every day, but you have to trust how I do that. I thought that kinship was interesting.”

Johnson continues, “His next trip in town, we had coffee and talked again. I suggested he might want to join our board. He said he’d be delighted to be considered… He’s been one of the most loyal board members; he has a really good attendance record. We started the tradition that he’d be the celebrity MC for our Making History Awards event. He did the digital versions during the pandemic.” Velshi has contributed in other ways, recently for example as the speaker for the museum’s Guild. He is also a speaker this year for the Chicago Humanities Festival.

Ali Velshi’s book is a family history, a personal perspective on immigration, and a demand that for those of us who have always known democracy, we must understand what it’s like to lose it.

“I’m trying to convey to people what wherever you are on climate or Israel and Gaza or any number of issues that you may be at odds with people on, none of it will matter if we cease to have a democracy. You will not have a choice, so fight to preserve your right to do that…. Autocracies are not born out of revolution. They are born out of the slow succumbing of rights by citizens to their leaders and that’s what we have to be careful of.”