Portrait of a Taos Artist

by Lenore Macdonald

It is not every day that one meets an authentic Living Treasure, but Taos-based jeweler Maria Samora is just that.

Born in Taos, New Mexico, and raised with a view of sacred Taos Mountain, Samora’s Native American father, Frank Samora, belonged to the Taos Pueblo. Samora’s Native American roots formed her world view and sensibilities.

Samora in her studio, filing an artwork at one of her vintage anvils. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

Growing up, she recalls that her brother, John Yellowbird Samora, showed the most artistic promise. Samora says his sculptures and other artworks, “were incredible and I wished that I could create beauty like he did.” Little did she know that she teemed with talent.

After graduating from Taos High School, she attended Pitzer College. She really liked it there, but “I just thought it would be fun to travel to a Spanish speaking country to learn Spanish and do my photography.” She went to South America and did just that.

The pull of Taos Mountain drew her home where she enrolled in a jewelry making course at University of New Mexico-Taos and waitressed to make ends meet.

In 1998, after working up the courage to ask goldsmith and master gem cutter Phil Poirer if she could apprentice under him, he initially said no. Then called her back and told her she could work part time—and “don’t quit your day job.” She worked alongside him for 15 years and waitressed to make ends meet.

She realized that there was no turning back.

Phil encouraged her talent, telling her to make her own designs. She did. He started selling her work alongside his. While waitressing she also started selling pieces to customers literally right off her back (or fingers or wrist or neck or ears). In 2005 she bravely, and fearfully, struck out on her own.

Samora’s 18K gold, five-band Leia-square cuff encourages the beholder to consider Native American ceremonial bracelets in a new way and medium. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

Blue Rain Gallery owner Leroy Garcia was in and out of the restaurant, asking about her pieces and if she would show at his gallery. At that time, the now iconic Blue Rain Gallery was on the Taos Plaza, not in its current spectacular space in Santa Fe. It was a more traditional Native American gallery.

Samora declined his offer, feeling that her contemporary work would not fit in with Blue Rain’s more traditional Native American offerings.

Time passed, she kept making jewelry and she started selling rings in the Taos Ski Valley between ski runs. They sold like hotcakes. Her friends encouraged her to start selling the rings through Garcia’s Blue Rain Gallery. She did and his business continued to grow and grow, much like hers.

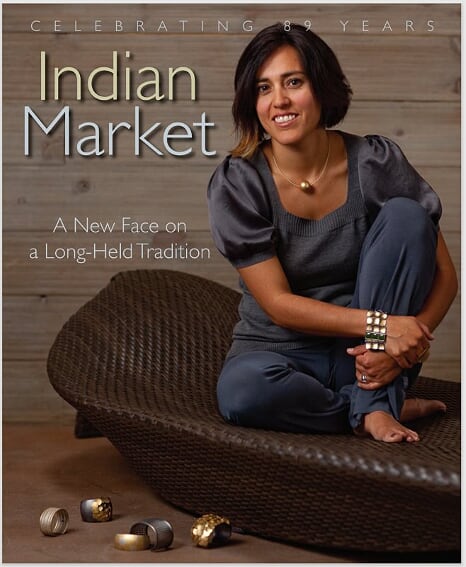

Garcia encouraged her to submit her work to the famed Santa Fe Indian Week Market. She did and was a hit.

SWAIA Indian Market Catalogue featuring “A New Face on a Long Held Tradition,” Maria Samora. Photo courtesy of Southwestern Association for Indian Arts.

After that, she was so successful that she was able to give up her “day job.” All of her hard work and perseverance was paying off.

Samora’s art evolved. She was very nervous, worrying that collectors would just walk away. Instead, they were happy to see something new, something other than the run-of-the-mill turquoise and silver they had come to expect from Native American artists.

Perhaps one of the most adorable Taos photo shoots in recent times, young Taoseños “raid” Taos’ Centinel Bank vault bedecked in Samora’s designs. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

Samora’s wearable sculpture—some would call it jewelry, but I would beg to differ—is very contemporary but grounded in nature and her Native American culture. Her designs, many hand-forged with antique tools, echo and distill the essence of the traditional motifs. The natural world may not always be obvious at first glance but forms the substance and the heart of each piece.

The rest is history.

Samora simultaneously evokes the spirituality of ancient Egypt and Native American culture in this lotus pendant with an exquisite Kingman turquoise drop. Turquoise figures greatly in Native American culture. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

Just four years after entering the 2005 Indian Market, she was the 2009 Poster Artist. She trailblazed as the first woman jeweler, youngest artist and third woman to be so honored. At that point, she says, “I went all in on contemporary” and her career skyrocketed.

Today, she designs and fabricates with her team at her atelier and shop, a century-old rehabbed stable at the foot of beautiful Taos Mountain just north of town on the Pueblo Road. She likes to “keep things simple reflecting Taos’ simple and grounded lifestyle of being one with nature.” Her work reflects her “deep native roots and the native traditions.”

Reminiscent of the Southern Sangre de Christo Range of the Rockies, home to Taos, Samora’s tetrahedron bracelet with black diamonds is imbued with both a sense of place and Native American culture in a modern, yet classic, way. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

Samora wants to break the boundaries of the stereotypical native jewelry, designing what speaks to her and comes from the heart. She likes “texture and depth, from a grounded feeling,” then “shapes and reflects that in a unique way.”

Unlike some artists, she is thrilled that other Native American artists are emulating her breakthrough “style and branching out from the usual Native stereotypes.”

Samora’s stunning, sculptural gold lattice ring echoes the local topography. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

It was inevitable that the fashion world would find Samora, even if she were creating far from the madding crowd. How could it not?

She and her minimalist sculptural artworks have been featured in Vogue—most recently in August1–and at New York Fashion Week. Last year she received an invitation to apply to the juried Milan Jewelry Week. She submitted four pieces and was accepted. The show featured 150 international artists representing 40 countries. She reflected, “it was fun to be part of something that wasn’t Native American. The artists knew nothing about Santa Fe Indian Market Week. Instead, I was identified as being from the United States.”

Samora submitted this double dreamcatcher bracelet to the juried International Milan Jewelry Week, interpreting an iconic Native American motif in her contemporary way. Samora notes that there she was viewed there as an “American” artist, not a “Native American” as she is often referred to in the United States. Photo credit Kevin Rebholtz 2020

Samora was named a Living Treasure by the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in 2018. It is a tremendous honor, all the more so because she is relatively young. She said, “it was a humbling experience, especially given the caliber of the artwork there.” She had a “mixed bag of emotions because it acknowledged and recognized her talent and accomplishments, but also gave her a chance to reflect on life and how she got to this point.”

Maria Samora, Living Treasure. Courtesy of Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

Grateful and blessed is how Samora describes her life. She is a humble wife and mother who sees and treasures the beauty and good in those she meets and, in the world, around her.

To learn more about Samora and her artwork, visit https://mariasamora.com/

Samora is still represented by Blue Rain Gallery. Visit https://blueraingallery.com/artists/maria-samora

Samora’s work can be viewed through April 18, 2021 at The Harwood Museum’s Contemporary Art / Taos 2020, visit https://www.harwoodart.org/cat-2020, https://www.harwoodart.org/maria-samora and http://harwoodmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/239

She is also scheduled to show at the Taos Pueblo Artists (Virtual) Showcase at the Millicent Rogers Museum October 16 through 30, 2020, visit www.millicentrogers.org

She is scheduled to show at the Albuquerque Museum’s ArtsThrive, October 24 through November 8, 2020 https://albuquerquemuseumfoundation.org/artsthrive/.