A rodeo on the Farwell XIT Ranch

By Megan McKinney

Founders of Chicago’s great 19th century companies and industries well knew the American West. Although some had built initial success on ore money, others participated in the region’s robust glamour after the personal fortune had been established. The Farwell brothers received the ten counties of the Texas panhandle in exchange for funding the capitol building in Austin; the Butlers kept buying chunks of Montana and South Dakota and Walter Paepcke turned a forlorn Colorado ghost town into a glittering ski resort, Aspen. Even Marshall Field and Levi Leiter added $1 million each to their considerable dry-goods hoards from a silver strike in Leadville, Colorado.

For others the wide country provided a foundation on which they built Chicago wealth. Philip Armour walked across the whole of America before staggering gaunt and barefoot into Placerville, California in 1854. When he rode out it was with an $8,000 stake toward becoming a Chicago meatpacking tycoon and legendary one-third of the triumvirate that ruled the city’s business world. George Pullman kept returning to Colorado to patch together funds for his first luxe sleeping car. And the Bordens used capital from their Leadville strike with Leiter and Field to set up a real estate partnership with Potter Palmer, a deal which brought Borden heirs wealth for generations.

The West was glamorous, exciting and rich in precious gold and silver, but it was also rough, seedy, coarse and dangerous. The boundless space was in sore need of civilizing and–before the end of the century–one man, more than any other, is credited with doing so. Furthermore, there are Chicagoans a century and a half later who live very happily because of this man.

His name was Fred Harvey.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Fred Harvey as a teenager

The 17-year old arrived in New York from London in 1853. about the same time Potter Palmer, Marshall Field and Levi Leiter were clustering in Chicago, where together they would create the department store industry.

Retailing would not be in Fred Harvey’s future. And he hadn’t yet thought of rail lines or restaurants. As he walked east from the Hudson River piers on that spring day–alone and hungry–he only knew that his immediate need would be to seek out a good meal, followed by a job, any job. The two pounds in his pocket would not last long.

As he continued walking, Fred came to a two story, square block grouping of buildings. It was the Washington Street Market, which he would soon learn was New York’s—and America’s–largest meat and produce source.

The Washington Street Market

Those who worked in the market–and whose livelihood was in recognizing excellence in meat and produce–ate at Smith & Mc Nell’s, a nearby restaurant at Fulton and Washington Streets. The high volume downtown spot was known for fresh ingredients and quality service. Harvey would not only be able to find a hearty meal at Smith & Mc Nell’s, there would also be a job at this restaurant, a miserable job—pot scrubber—but nevertheless a job.

Smith & Mc Nell’s

In his definitive book on the subject, Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West–One Meal at a Time, Stephen Fried informs readers that Fred moved up quickly from pot scrubber, through bus boy, to line cook, learning lessons he would never forget about excellence in large scale dining. Observing Henry Smith and Tom Mc Nell operate not only taught him about the importance of quality in ingredients and service but he also learned something about what were considered the pair’s eccentric business practices. They dealt only in cash, did not ask for credit and never extended it. Thirty years later Fred would be personally netting more than the equivalent of $1.1 million 21st century dollars annually by doing the same.

The Cabildo, from left, St. Louis Cathedral and the Presbytère of Fred Harvey’s brief New Orleans stay.

Following a year and a half with Messrs. Smith and Mc Nell, Fred’s first American adventure was to sail down to mid-19th century New Orleans, where he quickly learned of the city’s dismaying lack of employment possibilities. He was also appalled by the slavery surrounding him and the prospect of a war into which he might be conscripted to defend that slavery. He left very quickly.

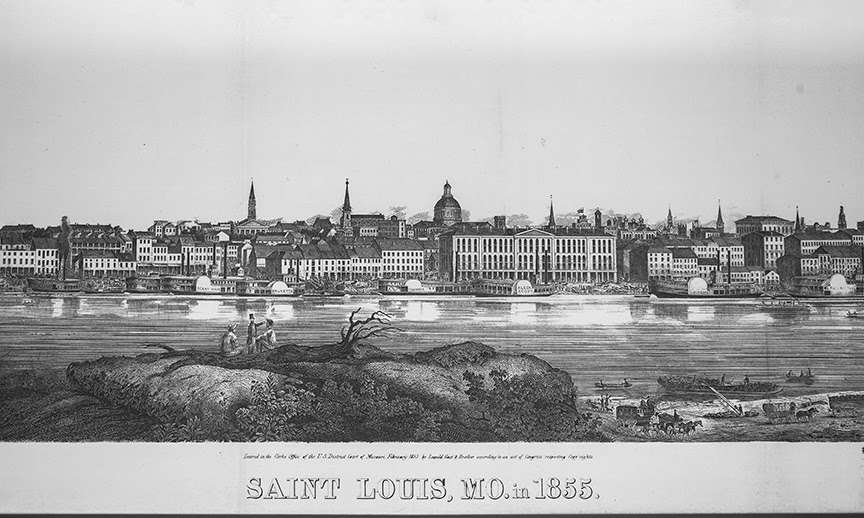

The next trip was up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, where he found a job he liked at the Butterfield House owned by an Abner Hitchcock, was to sponsor him for United States citizenship.

Fred Harvey in St Louis in the early 1860’s.

As the decade moved along Harvey took his first leap into restaurant ownership with a partner, William Doyle, a 38 year old Irishman. Their Merchants Dining Saloon was remarkably successful and might have continued to be so indefinitely without the Civil War. Fred ran the dining room and Doyle oversaw the saloon. They had been in business for one year, and Fred in America for six, when he made his first trip back to England. He returned to Missouri with his father, Charles Harvey, his sister, Eliza, and a Dutch wife, whose name was Ann. After a few weeks, Fred’s father went back to London; however Eliza remained in St. Louis. She had met Henry Bradley, an English bookkeeper, and stayed to become his wife.

It would be an eventful era for many Americans, with the explosive growth of the nation and a devastating war brewing, but for Fred Harvey it was also a time in which one major life event and/or tragedy followed another. The first episode was the 1861 birth of Fred and Ann’s son, Eddie, followed by a serious political argument between Fred and his partner, William Doyle, who was pro-slavery. After the argument, Doyle vanished, along with their shared treasury. Fred never saw either again.

A positive—and necessary—move forward was his association with Rufus Ford, a “packet boat” captain, whom he had first known as restaurant customer and friend, which was fortunate because Fred would need understanding.

St. Joseph, Missouri from the Kansas side of the river.

To join Captain Ford’s boat company, Fred moved his little family to St. Joseph, a Missouri River town of less than 9,000, and shortly afterward he became gravely ill with Yellow Fever. The disease nearly killed him and it was a long climb back to health; in fact, it was an illness that would mark Fred Harvey for the remainder of his life.

Soon after, another child was born to Ann, a son they named Charles for Fred’s father. However, it was now Ann who was deathly ill from complications surrounding the baby’s birth. Ann could not be saved and was soon dead at 27, leaving Fred alone with two children under the age of two.

Someone was needed to care for the boys, to cook and clean for Fred and to otherwise nurture him. Within four months of Ann’s death, he married Barbara Sarah Mattas, or “Sally,” a 19 year old Czech native, the eldest of a large working class family, who was—throughout their long marriage—thrilled each day to be the wife of a continuingly upwardly mobile man. Fred never had a problem at home and she apparently did not bore him.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Sally Mattas.

Fred had two more unbearable tragedies to face before this period of his life was finished. First it was little Charley who contracted scarlet fever and could not be saved from this now curable illness. Then, nine days later, Eddie died of the same disease on the day of Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox.

Fred Harvey’s was a life that would have to improve.

Classic Chicago readers who are enjoying our Fred Harvey series will be interested in the 2020 Fred Harvey History Weekend. Here is the link to learn about the annual November event–virtual this year–which is hosted by Fred Harvey authority Stephen Fried. https://www.eventbrite.com/e/fred-harvey-history-weekend-2020-online-6-talks-over-3-days-tickets-123954365845

The story of Fred Harvey will continue as a portion of Megan McKinney’s Classic Chicago Dynasties.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F.Carl