The 1963 Loyola Ramblers fought through Ku Klux Klan threats and racist taunts to win the only NCAA basketball championship captured by an Illinois school.

By David A. F. Sweet

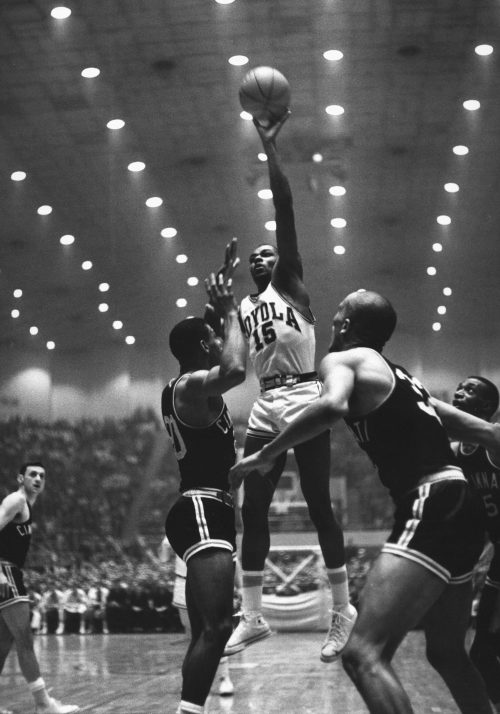

Words like Internet, Watergate and voicemail would have flummoxed Loyola University basketball players during the 1962-63 season, as they were years away from entering the common lexicon. The student-athletes couldn’t imagine the national basketball tournament that year — one they reached courtesy of their 24-2 record — being canceled by something called the coronavirus, which recently shut down March Madness.

But there is a word that was prevalent then and still exists today: racism.

Jerry Harkness didn’t score a basket in the first half of the 1963 championship game — but then he came on strong. Courtesy of Loyola Athletics.

The battle for civil rights gripped the country as blacks tried to end the era of colored waiting rooms and Jim Crow laws in the South. Four black girls died during a bombing of an Alabama church. Civil rights activist Medgar Evers was shot and killed. Trying to unite all races amid the madness, Martin Luther King Jr. offered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Within this historical context, Loyola in Chicago played basketball. Though there was an unwritten rule across the land that only two blacks should be on the court at one time, coach George Ireland, a white man, flouted it each game by starting four. Not only that, when the Ramblers would play an all-white team, Ireland was fixated on destroying his opponent, keeping his starters in even when they were ahead by 30 points or more.

“It was a social vendetta,” said Jack Egan a guard from Chicago and the only white starter on that squad. “The year before, we played Loyola of New Orleans, an all-white team. Our black players had to stay in homes; the white players stayed in a hotel.

John Egan’s playmaking skills were important to Loyola’s success against the defending NCAA champion Cincinnati Bearcats. Courtesy of Loyola Athletics.

“We were crushing them, and Ireland still had us pressing on defense until the end of the game.”

As Loyola’s wins mounted during the 1962-63 season, the Ramblers became a target of opposing fans in the South. Taunts such as “our team is red hot — yours is all black” assailed their ears, according to the documentary Iron Five.

“Houston was the worst,” recalled Egan, talking about when the team played the all-white Cougars in Texas. “The fans were throwing things. That was the only place we could have gotten physically hurt.”

Then, they lost three players — two of them key — during a semester break because of poor grades. As the NCAA tournament opened, only nine players were suited up.

Jerry Harkness, a forward and two-time All-American who grew up in Harlem before moving to the projects in the Bronx, remembered marches in Chicago as Loyola opened the tournament at Northwestern University. Marchers were bringing attention to the fact that black students in Chicago were mired in overcrowded conditions while there were openings at white schools.

Jerry Harkness received fear-inducing letters from the Ku Klux Klan during Loyola’s championship season. Courtesy of Loyola Athletics.

The Ramblers proceeded to beat all-white Tennessee Tech 111-42 — still the biggest margin of victory in the history of March Madness.

Then, the college students were introduced to the real world.

“A few days after that, I got the mail,” Harkness recalled. “The Ku Klux Klan is saying you better not play in the next game.

“I called our coach. Other players got letters. I was really nervous and scared. They knew our dorm addresses.”

The Ramblers boarded the bus for their next game in Michigan. They prepared for Georgia Tech, because the previous two years, Mississippi State had refused to appear in the tournament and play against blacks. But the Bulldogs defied Governor Ross Barnett’s edict not to travel to Michigan to play Loyola.

Coach George Ireland barks at his players during a timeout in the NCAA Final.

Before the game, Harkness was warming up before he was called to half court to meet Mississippi State captain Joe Dan Gold. The slew of newspaper photographer flashbulbs going off was practically blinding – after all, seeing a white man from the South and a black man from the North shake hands was almost unheard of — and the picture spread across the country.

“I looked at Joe Dan, and I felt a goodness about the whole thing,” Harkness said. “I felt he was sincere. When I went back to the huddle, I thought, “This is more than a basketball game. This is history.’”

After defeating Mississippi State by 10 points, Loyola easily dispatched rival Illinois and Duke University to reach the title game. It was played in Freedom Hall in Louisville against two-time defending champion Cincinnati, which meant there would be a rabid contingent of Bearcat fans making the 90-minute drive to the game. Loyola started its four black players; Cincinnati started three. It was the first time in the NCAA Finals the starters for both teams were mainly black.

Harkness was held to zero points in the first half, a shocking result for Loyola’s top scorer. The Bearcats grabbed a 15-point lead in the second half with only 10 minutes to go — this in an era before the 3-point shot and shot clock, giving the Bearcats a seemingly insurmountable advantage.

Said Harkness, “I remember saying during a timeout, ‘Oh God, please make it close.’ I was just embarrassed. We were on national TV for the first time, and people were watching me back in New York.”

Suddenly, as the season looked lost, Harkness caught fire. After a Loyola basket, he stole a pass and scored, which seemed to spur the team. With only seconds left in regulation, Harkness nailed a shot, sending the game into overtime.

The teams traded field goals during the extra five minutes. With the score tied at 58 and less than a minute remaining, a jump ball was called. Egan, the smallest Rambler at 5-foot-10, prepared to leap against a taller Bearcat player.

Egan got the tip.

John Egan was only 5-foot-10, but he won a crucial tipoff in overtime of the title matchup. Courtesy of Loyola Athletics.

“I knew he was going to get that jump ball,” Harkness said. “He’s just like that.”

With Loyola gaining control, Cincinnati knew Harkness would take the final shot. But as he started to shoot, he believed his defender had touched the ball, hurting his rhythm. Instead, he passed it to teammate Les Hunter. He missed his shot, but Vic Rouse put in the rebound just before time expired. Loyola 60, Cincinnati 58. The school on Sheridan Road remains the only Illinois team to ever win the NCAA Championship.

All of Loyola’s starters played the whole game — 45 minutes, including overtime. It’s said that coach Ireland didn’t believe in a sixth man.

Yet not every Rambler was celebrating afterward. Egan spoke with benchwarmer Jim Reardon — a top scorer in high school in the Catholic League — later that night.

Vic Rouse scores the winning basket for the Ramblers in overtime to win the NCAA Championship.

“I said ‘Jim, being here and winning it, would you have rather have gone to a smaller school where you got your 15 points and 10 assists a night but didn’t win the championship? He said, ‘I’d rather get my 15 and 10.’”

The years passed. Harkness became “the best of friends” with Joe Dan Gold, whose hand he shook at center court. They helped each other endure the plight of cancer, though it eventually took Gold’s life in 2011.

Harkness attended his funeral. After Gold’s family members were effusive in thanking him for coming, Harkness headed toward the coffin. Nearly half a century after meeting Gold, there it was.

“Right next to the coffin was a big picture, the one of us shaking hands,” Harkness aid. “I’ll never forget that.”

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be followed on Twitter @davidafsweet. E-mail him at dafsweet@aol.com.