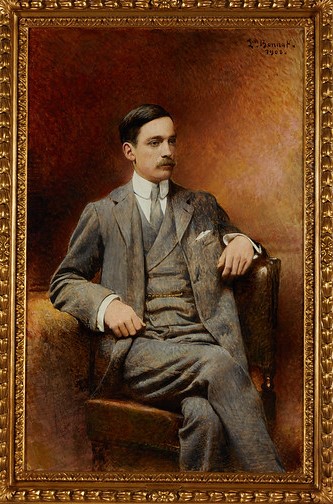

Marshall Field II

By Megan McKinnney

By the 1880’s, Marshall Field had become Chicago’s most powerful citizen; if he put his money and prestige behind something, it happened. He aided in the founding of Byron Laflin Smith’s Northern Trust, George Pullman’s Palace Car Company and Samuel Insull’s Commonwealth Edison.

Samuel Insull.

Among the companies in which he was a major stockholder were U.S. Steel and the Chicago City Railway Company, and he lent Joseph Medill funds to gain control of the Chicago Tribune. But his influence also had a dark side. He harbored a rabid hated of unions and a profound fear of socialists and political radicals.

The Haymarket Riots.

Following the Haymarket Riots, a trial of the accused anarchists produced a jury’s guilty verdict that would lead to their hangings, but many responsible citizens thought the verdict hasty and unjust. Banker Lyman Gage called a meeting of prominent Chicago businessmen to urge that the verdict be overturned and many agreed with him, if only for pragmatic reasons. However, when Field stood up and in a rare statement spoke against clemency, the assembled feared contradicting him.

The execution of the accused Haymarket Riot anarchists.

Field’s paranoia about labor unrest also led him to convince fellow members of the Commercial Club to donate the land for Fort Sheridan in north suburban Highwood, a military post that would protect their property and interests from the disgruntled masses.

Nannie Douglas Scott Field with the Field children, Marshall Jr. and Ethel.

He was the richest and most influential man in Chicago, in total control of himself and his surroundings—with one disastrous exception. In 1862, when he was 28, Field met a visiting Ohio girl, 23-year-old Nannie Douglas Scott, at a party. The next day, when he learned she was leaving town, he went to the train station to see her off. On a whim, he leapt on the departing train and proposed to her. And just as capriciously she accepted. It was an impulse both would regret for the rest of their lives. Nannie Field was tall, willowy and thought by the Prairie Avenue set to be somewhat Bohemian. She was, for example, the first woman in the Midwest to wear a tea gown, which proper Chicago thought highly unconventional (its loose-fitting silhouette suggested a negligee). And she invited celebrated actors and musicians to their house—not as paid performers but as guests—which horrified her peers.

An English tea gown from the late 1890’s when other women had begun to wear the style.

As her daughter, Ethel Lady Beatty, said much later, “Mother was born 20 years before her time” She was dreamy and sickly, devoted to the arts and astonishingly romantic, even by the standards of the day. But her husband was so tightly focused on his business that he could not give her the attention she craved, and the neglect she felt manifested itself in migraine headaches and vague psychosomatic symptoms. Ironically, the man whose motto was “Give the Lady What She Wants” could not unbend himself to give his own wife what she so desperately needed. The Fields had become trapped in an appallingly tempestuous marriage. Their dinner table arguments were the talk of Prairie Avenue children, who were sometimes present at mealtimes with little Ethel and Marshall II. Eventually, Marshall and Nannie lived apart; he alone in his mansion and she in France and England, from where rumors floated that she had become addicted to drugs. She died in Nice in February 1896 at the age of 56.

Ethel Field as a young woman.

The couple however indulged their children. The 1886 Mikado Ball they gave for 17-year-old Marshall II and 14-year-old Ethel was the most elaborate Chicago had seen. The décor for the ball, inspired by the popular Gilbert and Sullivan operetta, transformed the Field house into a miniature Japanese village.

“Three little maids from school are we” were lyrics from a favorite Mikado song.

The party was catered by Sherry’s of New York and required two private railroad cars to bring in linen, silver and food at a cost of $75,000. Special calcium lights illuminated several blocks of Prairie Avenue, and social Chicago’s favorite bandleader, Johnny Hand, provided the music. More than 400 guests attended the ball and received party favors designed by the painter James McNeill Whistler.

Ethel Field and two friends attended the ball costumed as the three little maids.

Marshall II attended Harvard and in 1890 married Albertine Huck, daughter of brewer Johann A. Huck, a German immigrant and Catholic, who in 1847 had opened the Near North Side’s first lager brewery. The couple settled in an English country estate, spending only a few months a year in their Chicago house at 1919 Prairie Avenue, a few doors away from Marshall’s parents.

Albertine Field with her two sons, Marshall III, top, and Henry. She and Marshall II would have a daughter, Gwendolyn, in1902.

A year later, 17-year-old Ethel married Arthur Magie Tree, son of Lambert Tree, a Chicago judge and one-time ambassador to Russia whose wealth came from Chicago real estate. The senior Tree is best remembered for the Tree Studios that he and his wife, Anna, established to encourage artists to stay in Chicago after the 1893 Exposition. The recently redeveloped Tree Studio building extends for a block along North State Street in an area that was once raffish and bohemian—a magnet for artists.

The Tree Studios inner garden courtyard.

The living and working units, designed to be stylishly arty with soaring ceilings, tall windows, skylights, loft bedrooms and stone fireplaces, were grouped around a European-style garden courtyard to which all of the artists had access. Among those who have occupied the studios are illustrator James Allen St. John, who created the Tarzan image, and his wife, the model for Jane; John Storrs, sculptor of the goddess Ceres that tops the Chicago Board of Trade building; Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs; and actors Burgess Meredith and Peter Falk. Completing the square block on the Wabash Avenue was the Medinah Temple, now a Bloomingdale’s store.

A small corner of Tree Studios today.

Although Ethel and Arthur were both Chicagoans, they met during a foxhunt in England. Both preferred that country to their own and, after their marriage, they took a Warwickshire estate neighboring that of Marshall II and Albertine. Their first two children, Gladys and Lambert, died in infancy, leaving only Ronald Arthur Lambert Field Tree, known throughout his life as Ronnie.

Ronnie Tree and his second wife, Marietta Peabody, were parents of the midcentury American model Penelope Tree.

When Ronnie was three, Ethel again fell in love during a foxhunt. This time it was with a dashing naval officer, David Beatty, later an Earl; together they bolted and she divorced Tree to marry him. Ethel not only abandoned her husband and their son, but she was also chronically unfaithful to Lord Beatty. She gave birth to two sons after their marriage—one son, David Jr., was his; the other, Peter, was fathered by one of Ethel’s lovers. An infection she transmitted to Peter at birth caused his later blindness, then suicide.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl

This segment of Megan McKinney’s Great Chicago Fortunes, Marshall Field, His World, will be followed by Marshall Field, The Legacy