By Margaret Carroll

Eleanor Page was tall and influential, like Chicago’s Tribune Tower and its namesake newspaper.

That is how I remember the Tribune’s longtime society editor as I first encountered her in the mid-1960s. Miss Page, as she was called by her assistants, held a degree of power. She and her staff covered the social lives of Chicago’s business and cultural elite. The morning Tribune usually carried the basic news of any social importance. As Miss Page and the other society reporters worked diligently to ensure that their stories had the early advantage (as did the Sun-Times staff), we at the afternoon Chicago’s American sought to compete by approaching our news from a different angle. The Daily News undoubtedly had its own coverage plan.

That was “back in the day,” as they say nowadays—back when society news still carried cachet—before Viet Nam and the Civil Rights and Women’s Movements of the ensuing years redirected readers’ attention.

Miss Page had been society editor since the late ’40s, after more than a decade’s experience as a reporter on that news desk. She had been trained by the redoubtable India Moffat, who later, as India Edwards, became a force in national Democratic politics.

Eleanor started working at the Tribune in the ’30s, a time when readers still enjoyed perusing news of descendants of the city’s early businessmen (McCormicks, Fields, Palmers, Swifts, Armours, et al). These were the subsequent generations, that is, whose members enjoyed and built upon or sometimes squandered the wealth earned by the grit and fortitude of the first generation.

Gradually the social set also welcomed other self-made men and their wives–helpmates in nurturing cultural and civic endeavors in the interest of “civilizing” the reputation of the city once described as “hog butcher for the world.” A few women who had inherited money of their own also were welcomed into top-tier activities. Among those excluded from the white-bread upper crust, some religious and racial groups formed their own clubs and supported their own causes. The papers made room in their coverage for the most sumptuous of their events. And Club Editor Irene Powers wrote features and covered certain events for many years as well, once describing her sphere as “everything the society desk doesn’t want and, brother, that’s a lotta territory.”

Society columns of those years did not question the status quo. The editors knew that their readers enjoyed ingesting a few titbits every day of “how the ‘other half’ lived.” It wasn’t entirely stodgy. At Chicago’s American (re-named Chicago Today in 1969), for example, the point of view of society editor Lois Baur was “Society puts its trousers on one leg at a time, like everybody else.” We who worked with Lois viewed the social scene with a touch of humor, but our coverage tried never to be mean-spirited.

From the mid-’60s on, however, observant readers might have noticed that society and Society were changing. Who would have believed that over the next decade or so, a woman for so long identified in the society columns as “Mrs. John Q. Public” would eventually be identified by her own first and last name, or that the title “Ms.” would replace “Miss” and “Mrs.”–then disappear entirely? Or that at least some of those previously excluded would be accepted on A-list charity boards? Or that as more women began working outside their homes, some charity boards changed meeting times to accommodate members’ work schedules? Or that certain private clubs would take down their “men only” signs?

Linda Landis Andrews, a Tribune society reporter in the ’60s, recalls her Tribune years as “the era of miniskirts, dress boots and emerging sexual freedom. Yet life in the ’60s on the Chicago Tribune’s society desk under Eleanor Page remained a dizzying whirlwind of cocktail parties, dinners, benefits, luncheons and special events such as the opening performances of the Lyric Opera and Chicago Symphony fall-winter seasons and the Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Fashion Show, the last a fundraiser for the hospital [now Rush University Medical Center]. The social pulse of Chicago vibrated from that desk.”

But Andrews, who now directs the work of writing interns at the University of Illinois at Chicago, also remembers feeling uncomfortable about the lightheartedness of her assignments during wartime: “The stories we wrote describing extravagance for good causes appeared in the same daily newspaper that was reporting on the Vietnam War and many Americans losing their lives in the jungles of Southeast Asia.” Like many others, she knew a young soldier who was fighting in Viet Nam.

In the war’s later years, some newspapers cut back on society coverage–private debuts, society weddings, etc.—deeming it frivolous. (Coverage was restored somewhat after the war, as time cushioned harsh memories.)

But earlier on at the Tribune, Miss Page and her four assistants gave readers a daily dose of the city’s social news, concentrating on fundraisers. The reporters dressed formally for formal occasions, as did two photographers assigned to the society desk. Sue Smith, another former assistant who later went on to managing editor-level jobs with the Dallas Morning News in her home state, recalled having “a closetful of formal gowns” when she covered Chicago’s social life.

Not that covering society news didn’t come with its own brand of pressure. Andrews credits Miss Page with “steely discipline and the skill of a master chess player.” The society editor was in charge of the flow of personal information about the city’s business, cultural and sometimes political wheelers and dealers. She decided which of any day’s myriad social events and “benefits” (charity fundraisers) merited coverage, knowing that those left out would complain—especially if they had friends in the social stratosphere.

Andrews recalled: “Miss Page kept a thick calendar book on her desk, and benefit chairs would call a year in advance to place their events’ dates date on it. One day the book disappeared–with ensuing panic. Many people were counting on the accuracy of this calendar and could not afford to have their benefits coincide with any other event competing for top-price fundraising dollars. One of the society reporters dumpster-dove, but with no luck. So the society reporters called every charity board they could think of, probably 200, to start a new calendar.”

And regarding personal news, the pioneers’ descendants hoped their names would appear in a newspaper—if at all–only for “births, weddings and obituaries.” Those events—and divorces, when discreetly mentioned—often were filtered through a little black book, the Social Register, which listed pertinent information (including otherwise unlisted phone numbers) about a given city’s elite.

As time went on, the unwritten rules relaxed a bit. Wealthy people who behaved themselves stepped onto the privileged path. All but the most patrician socially prominents became willing to reveal some insights into their private lives to benefit their always worthy causes—hence the growing competition for society column inches. In his 2002 Tribune obituary about Miss Page, James Janega recalled her telling a Chicago cultural board in 1969, “To me, people have to be doers.” She believed that in Chicago, charity work, not mere affluence, had the power to propel an individual into noteworthy social circles.

Miss Page worked long days, from 9:30 a.m. until sometimes after midnight, Landis recalled. And in those years before newspapers restricted personal contact between reporters and news sources, she entertained social-set friends in her home fairly often. One such event was an annual Kentucky Derby party, with guests placing small wagers while enjoying refreshments, then watching the race on TV. Winners divided the pot.

Some people may have considered Miss Page aloof. She was not much for casual office conversation except with immediate co-workers. Marion Purcelli, who worked her way up from copy clerk to editor of the Lifestyle section, said Miss Page–as she, too, addressed her–never, ever, spoke to her in their occasional interactions. But then–and after having rejected a number of the society editor’s story ideas for Lifestyle—Purcelli left the Tribune to work in real estate development. But one day before she left, she received a startling surprise. As Purcelli was waiting for a “down” elevator, she recalled, Miss Page stepped off the “up” elevator: “She nodded as she walked past and, after taking a few steps, turned and said, ‘I wish you good luck wherever life takes you . . . You have been a credit to the Tribune in general and to women in particular, and you have always been respectful to me during your years here.’ I was flabbergasted . . . and before I could reply, she turned, and, with those long legs and wearing a mantle of dignity, strode through the double doors heading into the city room.

“Truth be told I always considered the society desk one of the more valuable offices on the paper . . . that is, if the editor is an intelligent woman who has a nose for news, is a person with gravitas and, most importantly, a woman those persons she covers (or organizers of an event she attends) would be forced to treat her as an equal. I think Miss Page was the personification of Society Editors.”

If Eleanor Page seemed a bit distant in our meetings at events during my time as society editor at the American/Chicago Today (after Lois Baur died too young of cancer at 47 in 1966), I attributed it to the fact that we were both gathering copy for our respective columns. I learned later how generous she could be. While she directed the Tribune’s social coverage year in and year out, she also lived a private life with her first husband, Norman W.C. MacDonald, and their three children. Even if she had help at home, she surely juggled personal priorities and the contents of that bulging society calendar book. Like other women journalists of her time, she was disciplined and professional, a firm steppingstone for novices with ever loftier professional goals.

Although our relationship warmed as time went on, I can’t say I knew Eleanor extremely well. She was a private person in many ways. She lived in the affluent world I only visited. I saw her as dignified—although Andrews says her Tribune boss was not above telling an off-color joke. She did have a sense of humor, but I don’t remember hearing that joke. I do remember that when I moved from Chicago Today to the Tribune in 1974 (after the Tribune ceased publication of the paper it had purchased from the Hearst company in 1956), she welcomed me as a colleague.

And in early 1986, after she had retired, she did me a huge favor when the Tribune sent me to Palm Springs, Calif., to write about Chicagoans who wintered there. Eleanor and her second husband, Frank Voysey, were among those desert oasis sun-worshipers. Opening her Palm Springs phone book to help me set up appointments, she then ran my legs off in pursuit of interviews until I finally had to say, “May I have a glass of water?” Over several days, she showed me housing available at various price levels, golf and social clubs and a natural canyon suitable for a picnic. She introduced me to the fundraiser corps. And we visited residents’ homes, including those of Ebony and Jet magazines’ then publisher John Johnson, his wife, Eunice, and their daughter, Linda Johnson Rice; and former Chicagoan Dorothy Tenney, who had been married to Chicago orchestra leader Griff Williams and, after he died, to Walter Tenney, a Parade magazine executive, by then also deceased.

Eleanor Page MacDonald Voysey died at 88 in 2002. And although the media’s small-talk and gossip spotlight now has shifted to entertainers, sports stars and certain politicians, her reporting style continues on a modest scale. The Tribune highlights one fundraiser most Sundays in its Life+Style section. The photos show dressed-up “doers” smiling as they support a favorite cause.

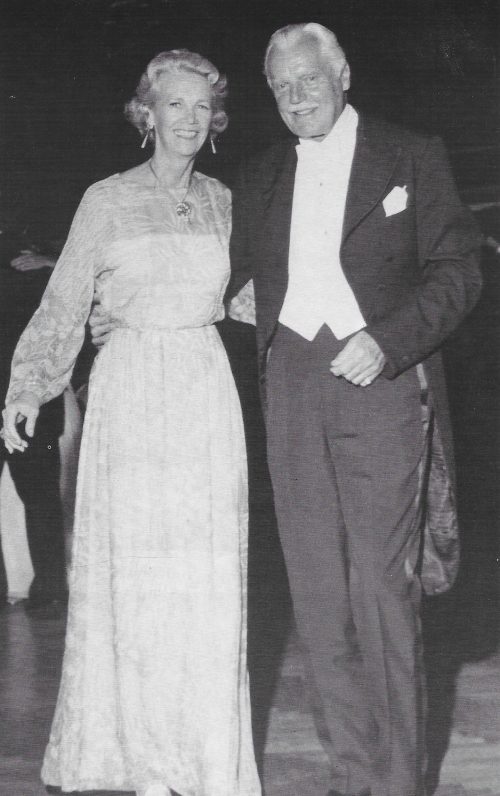

At the opening of Lyric Opera’s 1968 Season, Eleanor Page with Lyric’s Danny Newman on the far right. To her left are assistants Stephanie Fuller, Sue Smith and Linda Lee Landis, who is standing next to Miss Page. The photographers are Hardy Wieting and John Bartley, kneeling.

And the beat goes on.