By Judy Carmack Bross

The Jewelers Building, Chicago, 1882

The Jewelers Building, Chicago, 1882

For the first time, every remaining structure designed by Louis Sullivan is captured in striking color by one of America’s preeminent architectural photographers, James Caulfield. The story of Sullivan’s life and accomplishments, skyscrapers and ornamentation, students like Frank Lloyd Wright, and poverty at the end of his life, has been recorded by James’ long-time collaborator, Patrick F. Cannon. Louis Sullivan An American Architect is an absolute tour de force, more than 400 images in its 288 pages, cementing Sullivan as one of the world’s greatest architects.

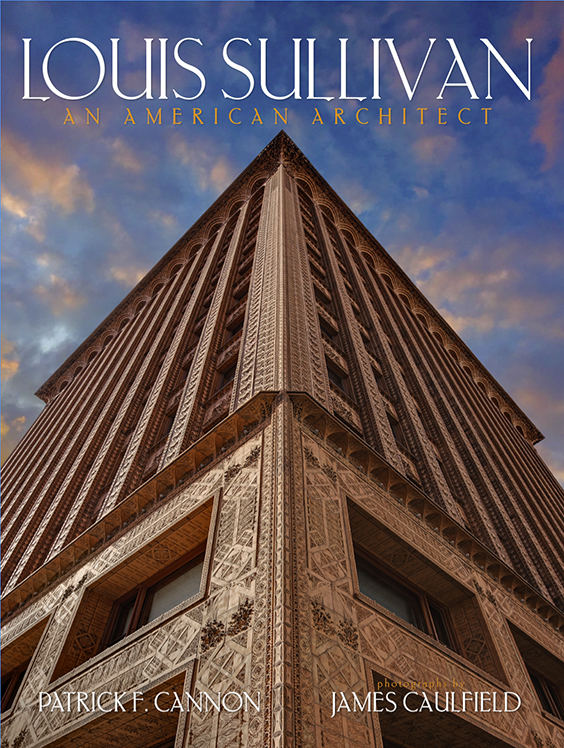

Front Cover – The Guaranty Building – Buffalo, New York – 1896

Published by Glessner House and made possible by a grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation, the book shows why Cannon and Caulfield have won three Gold Medals in architecture at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. We talked with them about the book which shows the range of the architect’s work from residences to skyscrapers, opera houses to banks, hotels to cemetery monuments.

“During this journey of more than a year, it’s been an honor to rediscover the 40 remaining buildings designed by Sullivan. I was truly taken with the exuberant color palette in which he worked, and which has arguably escaped wide notice, due to the preponderance of vintage black and white photography that predominately exists to inform us of his work,” Caulfield told us.

James Caufield

We asked Caulfield:

CCM: I have heard that every good photo tells a story. What were you trying to tell us about Sullivan in the photos you selected?

JC: As much of his story as can be told, must be told. A book has a limited number of pages, therefore the available ‘real estate’ is finite and nearly always insufficient. Most of the photographs I created of Sullivan’s buildings have unfortunately been left on the table, out of necessity. Those few that were ultimately selected for use had to contribute to the task of “telling at least some of the story”. But as I mentioned, the fact that I could capture Sullivan’s buildings in accurate color was arguably one of the greatest contributions, I think.

CCM: What is the main message that you wanted to share about Sullivan?

JC: The story of Sullivan, though truly sad from more than a few perspectives, was not a man I wanted the audience of this book to feel sorry for. Nor his buildings, regardless of the state I happened to find them in. To enable that outcome required me to make certain changes. That is, by removing things that were superfluous or obfuscating, or by adding things that were missing or had been badly replaced. Sometimes it was a rather simple digital repair. Other times, it was tedious recreation, one click at a time. No AI was used. I could personally see no reason not to improve the viewer’s perception where possible. Let’s just say I tried my best to make them present in the way Louis might have approved of.

“The purity of Sullivan’s process is key. He was a true artist and not given to compromise. It was both his greatest asset and his eventual downfall. I hoped that the book would adequately express this in a way that artists in the world could understand, appreciate and seriously ponder. I came to understand him. He felt familiar to me,” Caulfield said.

Pat Cannon

Author Pat Cannon told us how he first became interested in Sullivan.

“I took a course in 1968 in the Chicago School of architecture at Northwestern taught by Professor Carl Condit, author of the definitive works on the subject. We visited the newly restored Auditorium Theater on a field trip, and its magnificence was a revelation to me. Later, when I was working at City Hall, I watched the Stock Exchange being demolished; and the tragic death of photographer Richard Nickel, to whose memory our book is dedicated.”

The Chicago Stock Exchange Trading Room – Chicago, Illinois – 1893/1977. Now at the Art Institute of Chicago

“Over the years, I read more widely about Sullivan, and from his own works, and it became clear to me that not only did he want to become a great architect, but a great American architect. Here was a man trained in Paris, who could have had a much more successful career had he conformed to the accepted Eurocentric styles, but stubbornly insisted on a style based on American forms. His most famous student, Frank Lloyd Wright, would have been a different architect had he not worked and learned from Sullivan.”

We asked Cannon to tell us more about Sullivan:

CCM: His first inspiration was the Sistine Chapel, how did it shape Sullivan’s work?

PC: Although he was a talented artist in his own right, Michelangelo’s influence on Sullivan was more related to that artist’s single-minded dedication to his art. Sullivan was widely read, and would have been familiar with the concept of the Super Man, espoused by Nietzsche and others.

CCM: What is the main message that you wanted to share about Sullivan?

PC: In the mid to late 1880s, there was an explosion of tall buildings using steel framing. To Sullivan, their essence was their height and what he saw didn’t exploit this. The solution seems simple to us now — continuous vertical piers and recessed spandrels — but he was the first to see this logic. He was proud of this, but I think he was equally proud of most of his work. Sullivan should be remembered as a great American architect, but also as a guide and teacher. Young architects can still learn from his simple dictum: form ever follows function.

CCM: He arrived just after the Great Fire when our City was re-building, worked with Jenney and then was responsible for some of our greatest buildings. Is his an essential Chicago story? Would you encourage people to use your book to drive around and see his remaining buildings in Chicago and which are key?

The Charnley-Persky House – Chicago, Illinois – 1892

PC: While Adler & Sullivan had a national practice, I do think the atmosphere of innovation in rebuilding the city after the fire was a Chicago story. Indeed, early on, the eastern establishment began to see this new commercial style as the “Chicago School.” I would certainly encourage people to visit surviving Sullivan building, not only in Chicago but the banks throughout the Midwest . While we don’t print addresses, they can easily be found.

The Martin Ryerson Tomb – Chicago, Illinois – 1889

Louis Sullivan An American Architect is the first book published by Glessner House. Executive Director Bill Tyre told us about the Sullivan connection and shared a photograph of the Prairie Avenue House where Sullivan, who at that time, could no longer afford an office, worked in his last years.

“Glessner House is delighted to be the publisher of this wonderful new book exploring the surviving works of Louis Sullivan, captured in stunning detail by photographer Jim Caulfield. The topic is appropriate for two reasons. First, Sullivan was deeply influenced by the work of H. H. Richardson, the architect of Glessner House, and it is very likely he was one of the unnamed architects mentioned in Frances Glessner’s journals who visited the site during construction.

“Second, in the last few years of his life, Sullivan was provided with free office space by the American Terra Cotta Company, which had produced his iconic ornament. American Terra Cotta first occupied 1808 S. Prairie Avenue, the house adjacent to the Glessners; a few years later they moved their offices to the house at 1701 S. Prairie Avenue. As such, Sullivan would have often walked past Glessner House, no doubt reflecting on Richardson’s innovative design that shaped his own aesthetic.”

“The O. R. Keith house at 1808 S. Prairie Avenue, shown at left, is where Sullivan designed the Farmers and Merchants Union Bank in Columbus, Wisconsin. He was so proud of the project, he referred to it as a ‘jewel box,’ a term that was later applied to all eight of his bank projects.”—Bill Tyre

Although Sullivan was reduced to just a few commissions at the end of his life and lived at a cheap Chicago hotel, “he never stopped thinking and working”, Cannon wrote. Friends paid his debts after he died as well as for his grave at Graceland. His incredible body of work stands in tribute in Louis Sullivan An American Architect.

To learn more about Glessner House, the book, and upcoming events visit: glessnerhouse.org