By Scott Holleran

The Standard Oil Building: the skyscraper name evokes industry in a city once known as “the city that works.” Its original goal to propel one man’s legendary company was forged by drilling for oil in the depths of the earth and refining what comes out. Indeed, the skyscraper’s creator possessed a vision to conquer nature by constructing a beacon of steel and glass sheathed in clear, unbroken lines of marble extracted from Italy’s mountains. In its prime, terrorists marked the oil company skyscraper for death. This is the tale of Chicago’s brightest waterfront landmark.

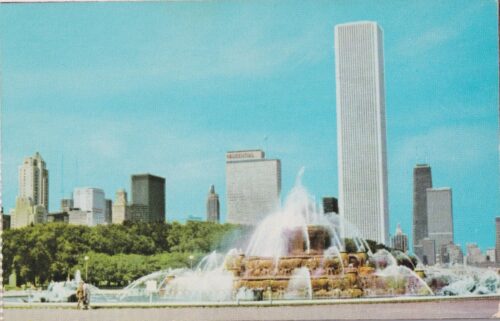

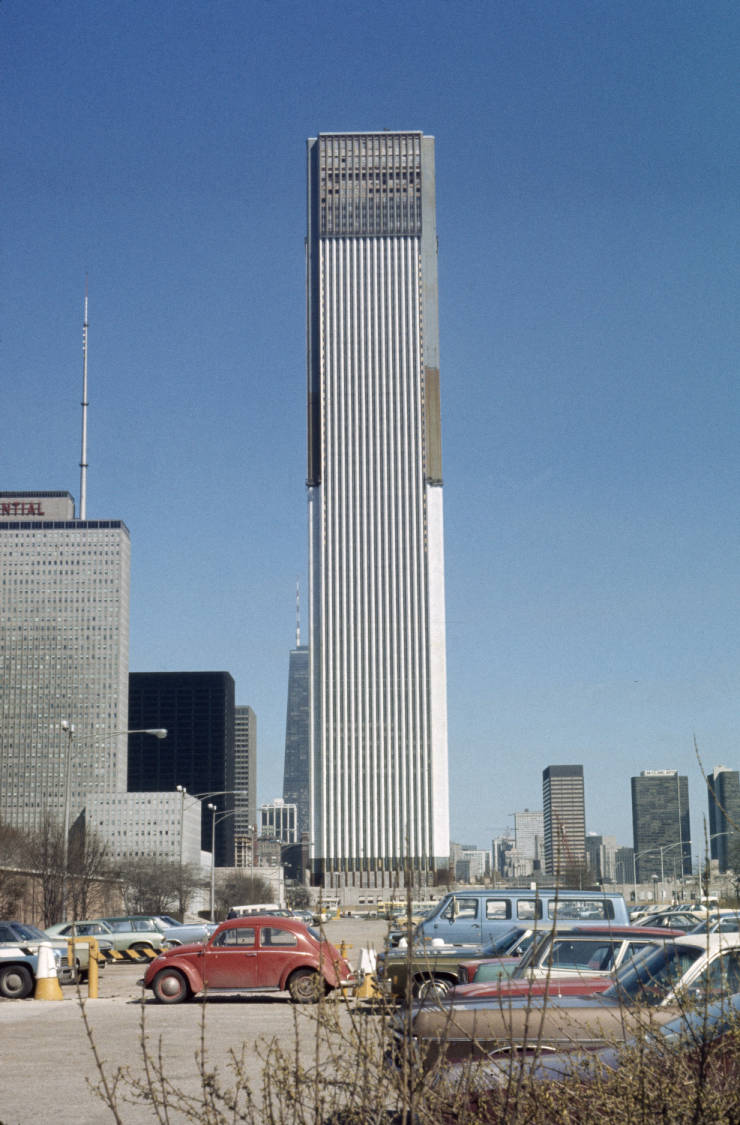

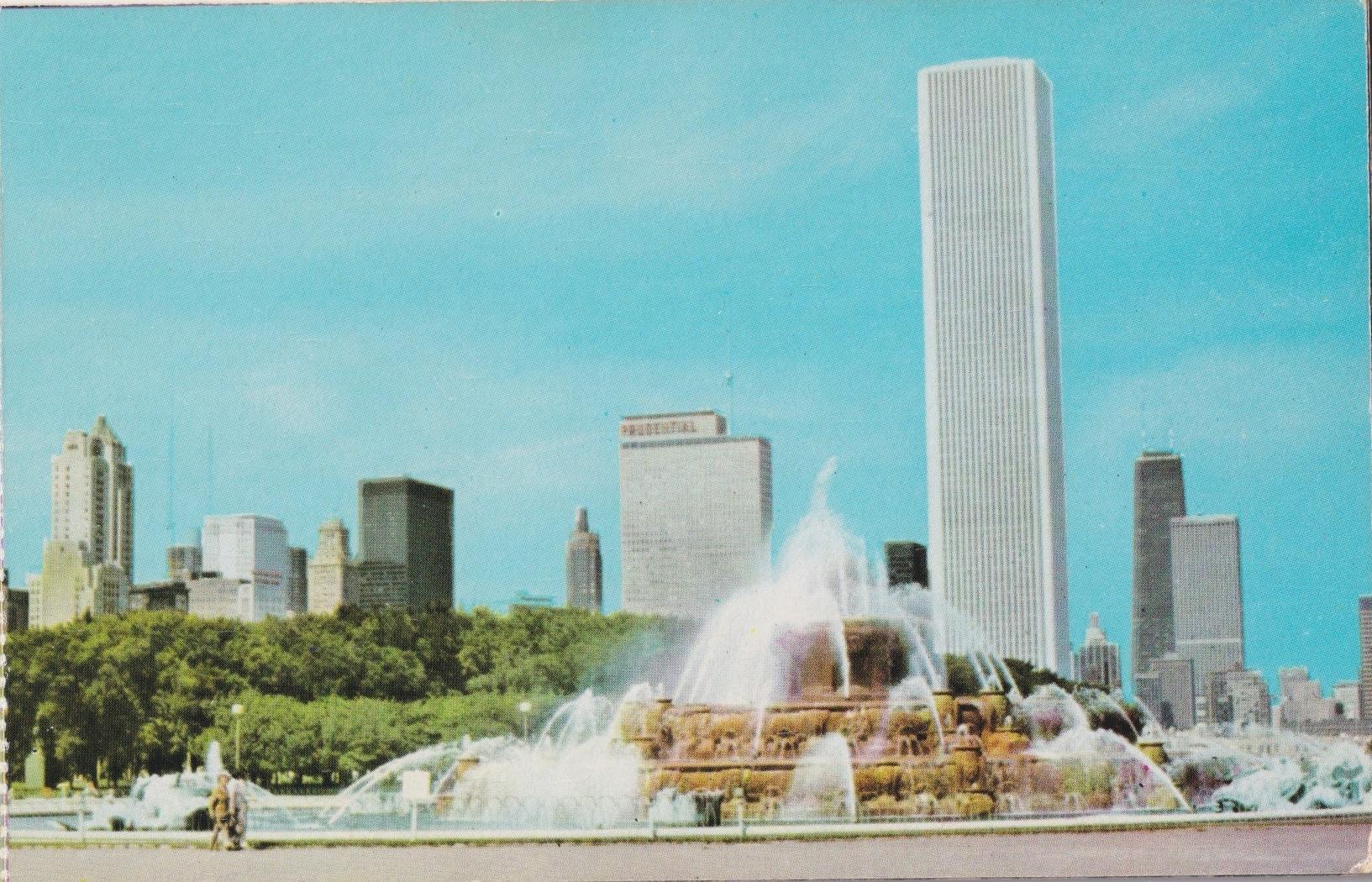

The gleam of this linear, ivory skyscraper—in contrast to the foreboding black Sears Tower and John Hancock Building—rarely gets notice, let alone respect.

Thirty years ago, Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamen dismissed the Standard Oil Building as a “visual non-entity.” By 2009, the Chicago Tribune was attacking the skyscraper’s fossil fuel-based name: “Who peers up from East Randolph Drive at the shimmering white Aon Center and mourns the loss of the Standard Oil Building, or that name’s successor, the Amoco Building? No one.”

Facts and the Big Idea

Is that claim true? What gave rise to the building? Why is it located on the great lake? Who designed and built the solid white tower and what was the big idea?

Designed by Edward Durrell Stone of New York City with shared credit by Perkins and Will of Chicago, both “attracted to [Italy’s] Carrara marble by its clear, white surface that is unblemished by veins of impurities,” the building was completed in 1973. Three years earlier, Standard Oil boss John Swearingen stood in the office of Chicago Mayor Daley—the father, Richard J.—announcing the oil company’s plan to build an 80-story 1,136-foot skyscraper in downtown Chicago.

“It will be the tallest office building in Chicago—31 feet higher than the rooftop of [the] Hancock office apartment building,” a Bensenville newspaper reported, noting that “[t]wo buildings in New York City will be taller…” The building was constructed as the international headquarters of Standard Oil of Indiana and its Chicago-based subsidiaries, including its Amoco oil and chemicals corporations. Mr. Swearingen forecast the project cost to exceed $100 million.

“The structure will consist of a slender tower on a block-square base structure below street level,” newspapers wrote. “The 190 ft. square tower with inset corners and predominantly vertical lines will extend 80 stories above a street level plaza at Randolph Street overlooking Grant Park to the south. The tower design is based on recent [industrial progress], utilizing the tube principle of structural design.”

Integrating an outside wall of five-foot windows, separated by five-foot triangular sections, which are part of the tower’s frame, Perkins and Will made the building to afford access to most mechanical services, such as utilities and air conditioning, through the triangular sections. The Standard Oil Building design permits flush window walls inside the structure. Equipped with 4,700 windows, its exterior consists of approximately 50 percent windows and 50 percent masonry wall surface. “The tower will be essentially a vertical, square tube,” journalists reported, “substituting a steel shell wall for the usual steel frame. The shell will be produced in large floor-to-floor segments, using automatic cutting and welding techniques.”

Chicago’s ubiquitous Turner Construction Company was general construction contractor. Frank M. Whiston and Company was contracted by Standard Oil as the tower’s exclusive rental agent and consultant.

A Big Oil Company and its Big Buildings

Standard Oil opened its first headquarters in Chicago in 1889. The company was headquartered at 910 South Michigan Avenue beginning in 1918. Its 5,400 employees were located in 12 various offices across Chicagoland by 1970.

Standard Oil Company founder John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) was the world’s first billionaire. Writing in his epic PBS series-paired large volumes The American Century and They Made America, Harold Evans notes that Mr. Rockefeller “became one of the richest and most powerful men in history. His innovation was to realize that although thousands of prospectors were digging oil wells, true riches lay at the point of refinery. Standard Oil, the massive vertically integrated company Rockefeller created, controlled 95 percent of U.S. refineries by 1878, but was split apart by the Supreme Court in 1911.”

Evans reported that “no one had ever seen such wealth.…[John D. Rockefeller] stopped going to his Standard Oil offices after 1897, played golf, and began giving away money in earnest.…By the time of his death at 97 in 1937, he had given away $530 million principally to medicine, black educational institutions and the Baptist-founded University of Chicago.”

The oil company’s architectural legacy extends to another iconic property—in Manhattan. In her long, slender 1996 volume on the world’s tallest buildings, Skyscrapers: History of the World’s Most Famous and Important Skyscrapers, Judith Dupre credits the Standard Oil founder’s only son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., for creating Rockefeller Center, “the only large private project executed between the start of the Depression and the end of the second world war.”

Young Rockefeller envisioned Rockefeller Center as a business complex; he sought to realize an epicenter of beauty—adorned with great works of art—and profit. Dupre wrote that “…Perhaps the most famous [art]work is one that isn’t there: Diego Rivera’s mural was destroyed when [Rivera] refused to eliminate a panel that appeared to glorify [Vladimir] Lenin.…” Other works include Lee Lawrie’s Atlas, holding the world aloft in the forecourt of the international building. Paul Manship’s Prometheus “…is a gem of yellow gold at the base of the RCA tower.” Rockefeller Center, made of steel and limestone, was completed in 1940—over 30 years before the Standard Oil Building went up in Chicago.

Standard Oil Company (Indiana)—as the nation’s sixth largest oil company was known—is the byproduct of John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company which, besides the Indiana firm, was sub-divided in a historic judicial ruling by the U.S. government in a historic, state-sponsored company disintegration creating Exxon Corporation, Mobil Corporation, Standard Oil of California and Standard Oil of Ohio. Standard Oil of Indiana operated under the name Standard in a 15-state Midwestern area, adopting the name Amoco in the American south and east. Overall, 24,000 gasoline stations carried these names. Only a small fraction of the gas stations were company-owned.

Mergers with Occidental Petroleum Company, Kennecott Copper Company and Blue Diamond Coal Company failed. In 1979, however, Indiana’s Standard Oil subsumed a copper company with the acquisition of Cypress copper mines. By 1980, Standard Oil’s stand-alone skyscraper was the fourth tallest building in America behind Chicago’s Sears Tower, the World Trade Center and the Empire State Building in New York City (and it’s a few feet taller than Chicago’s John Hancock Building).

The Standard Oil Building was intended to elevate the Standard Oil profile, as Chairman and CEO John Swearingen’s announcement in Daley’s office attests. As America’s “second city,” after New York City, Chicago was competing at this point in the later 20th century with Los Angeles. Mayor Daley rarely lost an opportunity to hustle and promote autocratic Chicago as welcoming to Big Business.

The skyscraper in progress stimulated intellectual imagination.

An article in a Sunday 1970 edition of the Tribune provides testimony that the prospective tower captured the city’s futurism. In the article, a Northwestern University professor detailed why he sought to tether Standard Oil’s rising tower to a third Chicago airport and what he saw as Chicago’s capitalist promise.

Suggesting a new Chicagoland airport on farmlands 40 miles south of Chicago, Professor Stanley Berge “said the airport should be linked to the city by high-speed trains operating on the Illinois Central right of way. Trains operating at speeds similar to the metro line between New York and Washington would allow travel from the Loop to the airport in 30 minutes…[h]e cited a study which predicted the amount of passengers coming through Chicago [would] double by 1975 as evidence of the need for a third airport. “I think we have to get busy on a third airport,” [Berge] said.”

The scholar argued that building a new airport far from the city which could be reached in a short time was ideal for Chicago. Citing pilot concerns about flying over Lake Michigan at low altitude in bad weather, which he said aviators thought could cause sudden air turbulence, icing and snowstorms, pilots were also concerned about disorientation while landing without landmarks and lights. Contemplating an island airport in the lake, Berge additionally pondered how that could affect circulation, lateral drift and pollution dispersion. Ultimately, according to the Tribune article, Berge forecast that airplanes could approach an island airport from three directions without passing over Chicago, which he thought would lessen the impact of noise and pollution.

Northwestern’s transportation teacher argued for a new airport linked to a high-speed train along the lakeshore from Homewood to Waukegan. He said commercial properties normally located at the airport, such as hotels and cargo terminals, could be located at points along the railroad line to prevent airport traffic congestion. Berge cited property near Peotone, Illinois as ideal because the area was primarily rural and located close to the Illinois Central Railroad.

This is the where the Standard Oil Building became a factor; the railroad Berge envisioned involved a tunnel under buildings along North Michigan Avenue to provide transportation for residents and workers in both the Hancock tower and the projected Standard Oil Building. Professor Berge saw the airport, fast train and skyscraper as the pipeline to feed Chicago’s industrial progress.

After the Standard Oil Building was built, the vision of a third major, let alone island, airport and tunnel-based fast rail transit moving passengers to the marbled skyscraper faded. The Italian marble turned out to be an expensive problem.

“Marble is weaker than limestone and granite—two other veneers that are gaining popularity as architects learn more about the shortcomings of thin marble cladding,” the Tribune reported in 1988. “And of the world’s many marbles, few are as fragile as the marble mined in Italy’s Carrara mountains, near Padua.…The stones’ inherent faults weren’t always apparent. That’s because, until recently, marble, like other stones, was used in big blocks for building.” The Standard Oil Building was among the first to be clad with thin sheets of marble and Chicago’s harsh weather eventually caused cracks to form. The building exterior was renovated in the 1990s with white granite.

Other sources connect lower Manhattan’s twin silver skyscrapers—World Trade Center, which opened in 1973 and was destroyed by Islamic terrorists in 2001—with the Standard Oil Building. In Chicago from the Air (2002) by Antonio Attini, the author writes that the design was “…inspired by the linearity of the Twin Towers in New York…The pure verticality of the gigantic Amoco Building was inspired by the same design philosophy of the World Trade Center in New York.”

Who’s the principal architect?

Architect Edward Durrell Stone had been at the forefront of America’s industry titans and cultural icons. Stone designed the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, India, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC and New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1937. In Chicago, Stone created the University of Chicago’s Center for Continuing Education, co-designed the Standard Oil Building and consulted on the original McCormick Place. Time magazine founder Henry Luce commissioned Stone to design a house in 1936.

Born in Arkansas, where he attended the University of Arkansas, Stone studied at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, though he never earned a degree. After traveling on fellowship, he worked on Radio City Music Hall’s design. Later in his career, according to various newspaper articles, Stone became fixated on decorative screens and indoor pools themed to Islamic architecture.

Stone, who was an alcoholic, proposed marriage to his second wife in 1954 during a passenger flight; they were assigned adjacent seats while flying to Paris. After the wedding, he renounced alcohol. The couple divorced in 1965.

Stone designed white marble facades for both the Standard Oil Building and New York’s General Motors Building. His architecture includes the National Geographic Building in Washington, DC, hotels in the Mideast, Caribbean and Central America—hospitals in Peru and Southern California—and a library in Davenport, Iowa, a city hall in Paducah, Kentucky, the Anheuser-Busch sports stadium in St. Louis, a bank in Nicaragua, an airport in Saudi Arabia, a mosque in Pakistan, a church in Schenectady and a synagogue in Cleveland. Stone designed Pepsi’s headquarters. Stone created an American world’s fair pavilion based upon an engineering principle—the bicycle wheel—in 1957. The Brussels, Belgium pavilion, inspired by Rome’s Colosseum, won gold medals. Frank Lloyd Wright called Stone’s U.S. embassy in India one of the finest buildings of the century.

Despite his success, the man who designed the Standard Oil Building was discouraged by aesthetics he observed in America, once commenting that “[i]f you look around you, and you give a damn, it makes you want to commit suicide. A bird’s eye view of our country might lead to the observation that Americans can afford everything but beauty…there’s a starvation of the spirit in this country. Man, deprived of beauty, aesthetic, pleasure, will turn in his ignorance to pleasures more base and brutal to alleviate the boredom. If you doubt me, take a look at our slums, at certain of our teenagers, or at a tired businessman or two.”

The Standard Oil Building appears to have given the architect a boost. In an October 31, 1971 newspaper profile by Jack Leahy, Stone expressed the conviction that “his best work lies before him.” “Until he’s 50,’ said Stone, “an architect is merely tooling up for his life career.…The reason why…[is that] nobody in his right mind is going to give $100 million or so to a boy fresh out of architecture school and that’s the kind of fantastic sums that must be [budgeted] to an architect for a major project. It’s a staggering moral obligation to take that much money, and then try to turn it into a building, which will eventually be worth more than the cost of its construction.”

“Early in his career,” Stone recalled to Leahy, “Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright said that he had to make a choice between hypocritical humility and honest arrogance. He decided to choose the latter. I’m afraid I may be guilty of the same attitude.”

Nationalism, Terrorism and Chicago

Once completed in 1973, Chicago’s skyscraper became a target for terrorism.

A Puerto Rican separatist group known by the Spanish acronym for the Armed Forces of National Liberation—FALN—terrorized Chicago, Washington and New York from 1975 to 1980. Puerto Rican nationalists, who had attempted to assassinate President Truman and wounded five congressmen on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, bombed a restaurant in New York City in 1974, killing four and injuring more than 50. Other bombings followed.

Early in the morning of June 14, 1975, hours before a Puerto Rican Day parade on State Street, dynamite was found in a bouquet of roses at the Standard Oil Building. Though the dynamite did not explode, several terrorist bombs did explode outside Chicago’s Midcontinental Plaza Building at 55 East Monroe Street and the United Bank of America at State and Wacker. Four people were injured. That fall, bombs exploded outside the IBM Building, Sears Tower and another bank. On that same day, five bombs exploded in New York and two in Washington.

Puerto Rican nationalists bombed 16 more times, attacking a Holiday Inn, the Merchandise Mart, U.S. armed forces recruiting offices, the Cook County building and the Great Lakes Naval training base outside North Chicago. On Saturday, June 14, 1978, six bombs exploded at noon in Schaumburg’s Woodfield mall. “The terror didn’t end until April 4, 1981,” the Tribune later reported, “[when] 11 people including 27-year-old…leader Carlos Torres were arrested near the Northwestern University campus in Evanston. They were about to try to rob an armored truck when Evanston Police, responding to a nuisance call, rolled up. Torres, who had attended high school in Oak Park, was paroled in 2010 after serving 30 years of a 78 year sentence.”

When construction finished in 1973, the Standard Oil Building was the 11th tallest building in the world the height in feet at 1,136 feet. Perkins and Will, integrating Mr. Stone’s design, had adopted a relatively new structural technique bundling the skyscraper’s elevators and other mechanics into the building’s core, with perimeter columns as an outer tube, linking its outer and inner tubes by trusses supporting the Standard Oil Building’s wide, open floor plates.

At 83 stories tall, the whole, integrated structure keeps itself standing. Chicago’s Sears Tower, under construction during the same time, used a similar tubular engineering and design model. Standard Oil became Amoco in 1985. Amoco sold the tower in 1998. The building name later changed to Aon Center. This singular symbol of industrial energy, vitality and refinery in oil, art and business, was conceived and built in the name of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

—

Award-winning author, writer and journalist Scott Holleran lived in Chicago for 21 years and writes Industrial Revolutions. Read and subscribe to his non-fiction newsletter, Autonomia, at https://www.scottholleran.substack.com. Listen and subscribe to his fiction podcast at https://www.ShortStoriesByScottHolleran.substack.com. Scott Holleran lives in Southern California.