Privileged, Yet Doomed

npg.org.u

npg.org.u

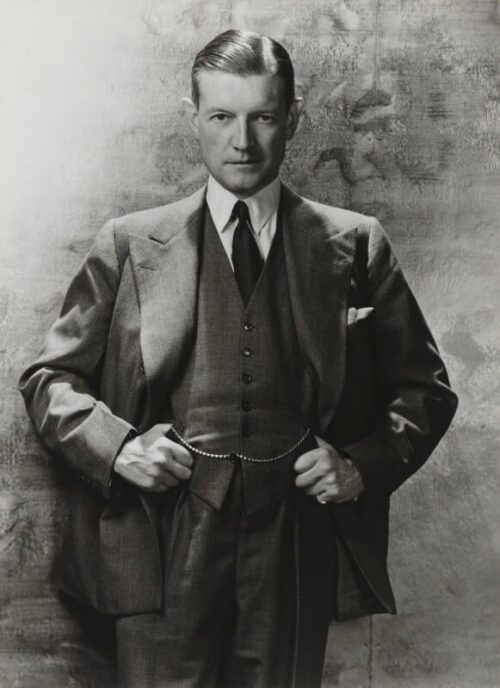

Sir Henry “Chips” Channon

By Megan McKinney

Those of Chicago’s Twilight Generation were born during the last decades of the nineteenth century. They grew to know a world of privilege “before the lamps went out” in 1914, and they experienced the texture of the years between the wars. Yet, the generation was touched by the drama and the tragedy of both World Wars, the Great Depression, Prohibition, and still another scourge of the era.

redfin.com

They had lived surrounded by extraordinary design and high style in their personal lives.

And at the beginning, their entertainment life with contemporaries had been centered in The Blackstone Hotel, the early twentieth century spot to hold every notable party from an elegant little tea dance to a full-scale debutante ball in the Crystal Ballroom.

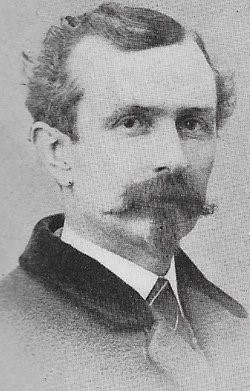

Potter Palmer

Their grandparents, born in the east in the 1830s—or as early as 1826 for Potter Palmer—were Chicago’s Founders, the men who created the city’s great industries and businesses, Marshall Field, Levi Leiter, Philip Armour, and George Pullman.

Marshall Field

And their parents were the generation of Heirs, who simply enjoyed the wealth the Founders had made possible. However, members of the Twilight Generation actually worked, or at least made twentieth century careers.

‘findagrave.com

‘findagrave.com

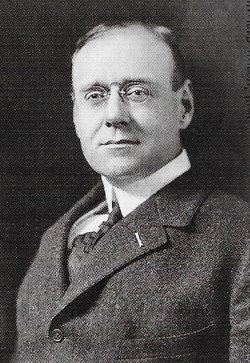

Leander James McCormick

There were two Leander James McCormicks in the Harvester clan. The Twilight Generation member was a painter, who lived from 1888 to 1964. He held a one‐man show in Paris in 1959, and—spending the years from 1947 in Saint-Tropez—was a regular contributor to galleries along the French Riviera. And, before painting in France, he had been a Chicago architect, collaborating with fellow Twilighter Andrew Rebori on the design of several buildings, including the Racquet Club.

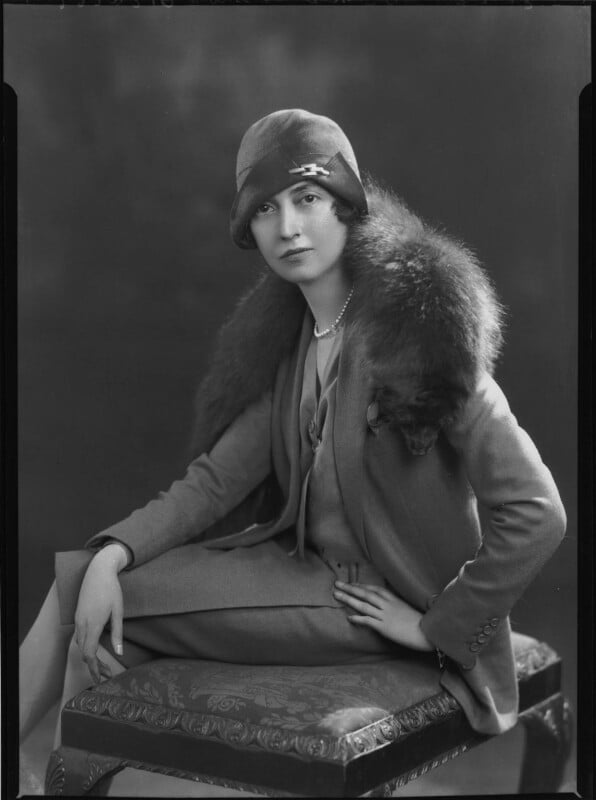

Mary Landon Baker

Mary Landon Baker did not work at a job, nor did she have a career, but she was nevertheless a notable Twilight Generation figure. During her lifetime, which spanned from 1901 until 1961, she received sixty-five—or possibly as many as sixty-seven—marriage proposals, including those from an Irish prince, an English Lord, and an immensely affluent Spaniard. Yet she never married. There was a close call at the Fourth Presbyterian Church on the bitterly cold afternoon of January 2, 1922.

cameratachicago.org

At the altar stood a fiancé, Allister McCormick, a best man, and two ministers. Waiting. The organist played through hymns and the expected wedding music staples twice, while guests fidgeted. It was then that one of the ministers was called aside and a message delivered.

chicagohistory.org

He learned, in essence, that when Mary Landon Baker stood in front of a full-length mirror in the Baker apartment on Lake Shore Drive, some blocks north of the church, and slipped on the bridal dress—a silk velvet sheath from House of Worth in Paris—she decided she would not marry Mr. McCormick. Or anyone. She kept that promise to herself and today the unworn wedding dress belongs to the Chicago History Museum.

findagrave.com

Hobart Chatfield-Taylor

Supreme among members of the Twilight Generation was Hobart Chatfield-Taylor. The family name was Taylor; however, his mother’s childless brother, the courtly and immensely affluent Wayne Chatfield of Cincinnati, made the boy his heir in exchange for adopting his name.

Wayne Chatfield

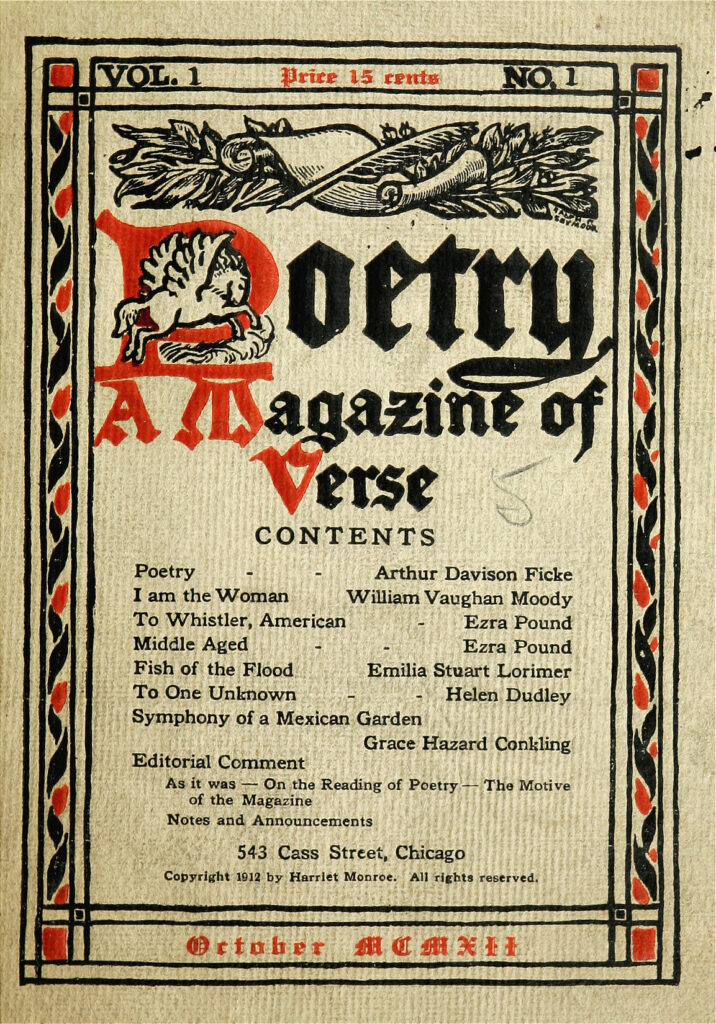

For several decades, there was not a Chicago social or arts-related event in which Hobart was not a central figure. He was co-founder of the weekly political review America in 1888 and was a catalyst in the start of Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine in 1912. He was also a special correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, and, in the early 20th century, he founded the Society of Midland Authors with fellow members of the Cliff Dwellers Club and was its first president. Among SMA members were Edna Ferber, Clarence Darrow, Vachel Lindsay, Jane Addams, Carl Sandburg, Lorado Taft, and William Allen White.

In addition to writing several successful novels and contributing to principal national magazines, Hobart was an expert on the French and Italian drama of the 17th century, subjects in which he lectured at leading universities and colleges. Additionally, he wrote major biographies of Molière and Goldoni, Molière’s Italian equivalent. And his foreign honors included decorations from England, France, Spain, Portugal and Venezuela.

playeatlas.com

That he was one of the very few younger men within the inner circle of the icy Marshall Field and was said to be a Ward McAllister to the lofty Mrs. Potter Palmer—who did not need a social adviser but treasured Hobart’s company—speaks for his charm and self-possession.

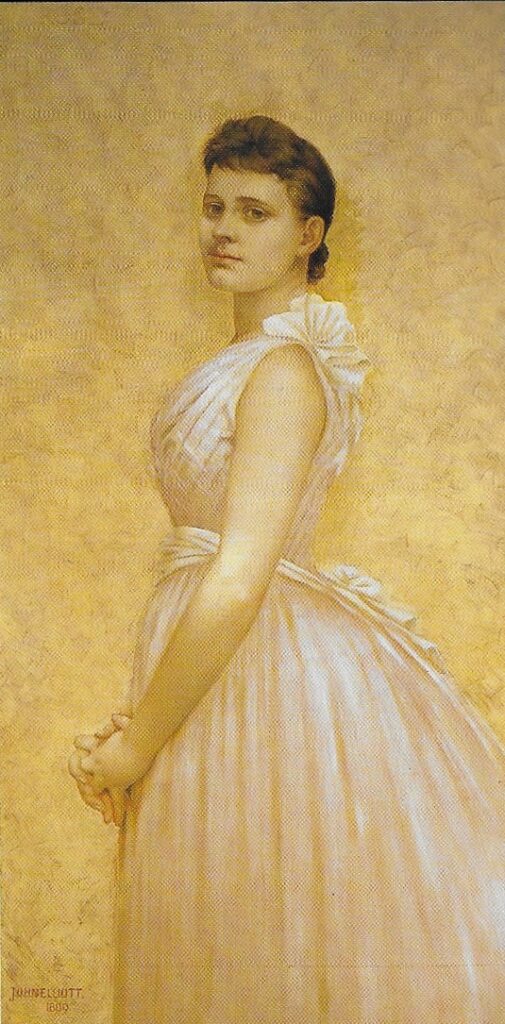

Rose Farwell by John Elliott.

In 1890, Hobart married Rose Farwell, one of the exquisite daughters of United States Senator Charles B. Farwell and the former Mary Eveline Smith of Lake Forest.

Hobart and Rose were members of the Little Room, a group of artists, musicians and writers who met for tea and fellowship on Friday afternoons following the Symphony. Initially, the group had no fixed location for meetings; therefore, they borrowed its name, Little Room, from a short story by a member, Madeline Yale Wynne, about a mysterious room that would magically vanish and then reappear when kindred spirits gathered as a group.

Chicago’s fabled Fine Arts Building is today inhabited by many legendary ghosts, including those of Little Room fellows.

After meeting for a time in various locations, members finally settled in Michigan Avenue’s Fine Arts Building in the airy two-story studio of Ralph Clarkson. It was an ideal location, for both Chatfield-Taylors and many of their friends who kept Fine Arts Building studios. Hobart wrote in his space, and, in hers, Rose bound fine books, utilizing a craft she had learned during a year’s study in Paris.

Following the death of Charles Farwell in 1903, Rose, Hobart and their children, Adelaide, Wayne, Otis, and Robert, lived at her father’s Lake Forest estate, Fairlawn, spending a portion of the year at their house in Santa Barbara.

Fairlawn

When the influenza epidemic of 1918 hit Santa Barbara along with much of the rest of the world, killing some seventy million people, forty-eight-year-old Rose was infected by this other, frightening scourge of the era, which joined the drama and tragedy of the two World Wars and Great Depression. Suddenly, tragically the beautiful Rose died, shattering the Farwell-Chatfield-Taylor idyll.

Following her death, Hobart decided to make Santa Barbara his full-time home and donated his library of French and Italian literature to Lake Forest College. In 1920, he married Estelle Barbour Stillman, a widow.

Author photo: Robert F. Carl