By Francesco Bianchini

Mother was convinced that a tea party was a good opportunity to bring the family together. At a time of day equidistant between lunch and dinner, her teas coincided with breaks in our schoolwork and/or afternoon amusements, but more often than not, with the arrival of some visitor. We lived in the country and that’s how it was: there was always someone knocking at the door just because they happened to be passing by, perhaps accompanied by friends or children the age of one of us. Thus from the four corners of the house, we seven siblings migrated to the living room where, for much of the year a fire burned in the fireplace, or in better weather, to the porch overlooking the garden.

La Cervara, our family home in the Umbrian hills

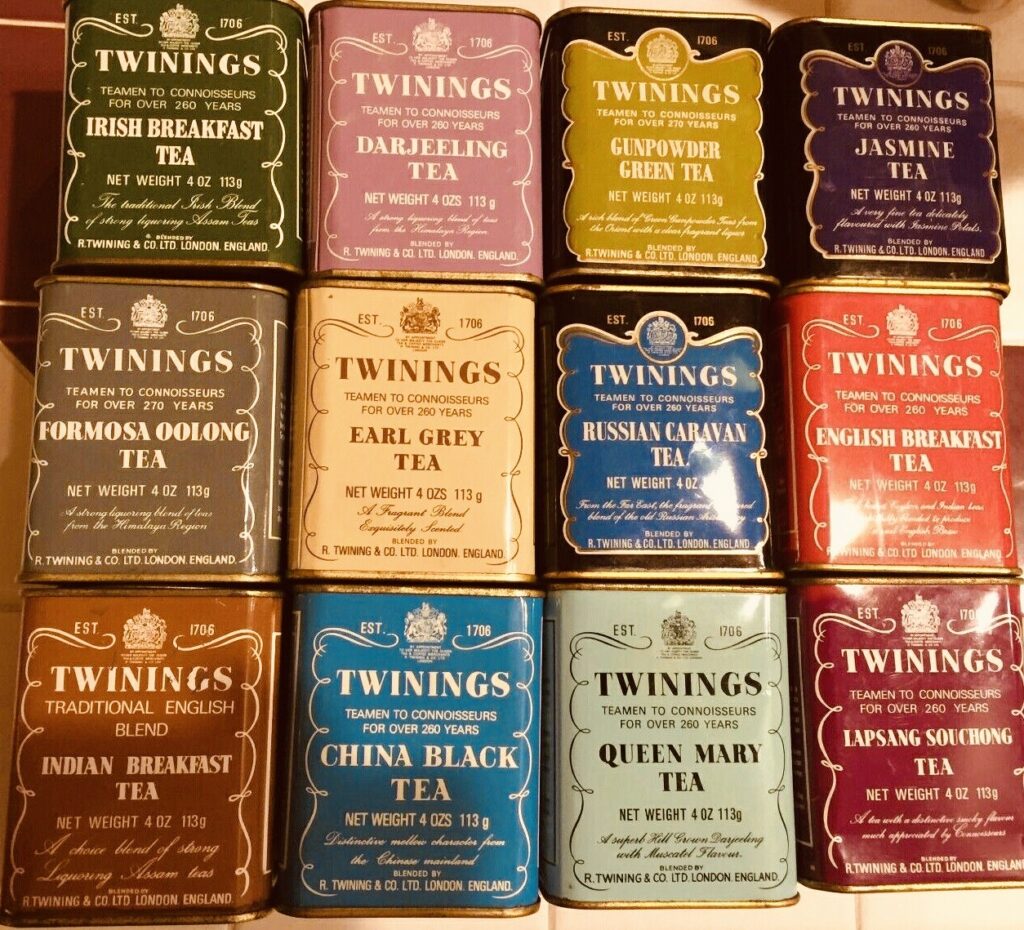

Mamma had lined up on the shelves of a narrow kitchen cupboard a fine display of tin boxes of the tea blends she had accumulated over the years, and she’d go through them with obvious pleasure, choosing one she thought suited the day. ‘With Rodolfo’s somewhat heavy lunch,’ she’d mutter, ‘black tea flavored with vanilla will do,’ or with some vehemence, ‘you’ve gotten me upset today, so this apple and cinnamon will soothe me!’ Tea for her was a panacea against ailments and sorrows, and although in later life she has taken to collecting teapots of every shape and kind, at that time in my childhood she usually resorted to a low, pudgy pewter one, like Mrs. Mingott in The Age of Innocence; awkwardly heavy to manoeuver, with a dangerously fissured ebony handle, but her most capacious.

Mamma’s pride and joy

From out of the kitchen she pushed the trolley toward the living room, and the clatter of Deruta cups – baritone compared to the more shrill tones of the porcelain we did not often use – heralded her transit over the seams of the terra cotta floor. On the bottom shelf of the trolley resided, as the case might be, a plumcake she’d made, fluffy and moist, or an Umbrian rocciata that everyone in the house insisted on calling ‘strudel’, or even some Christmas or Easter cakes if we were within the sphere of those holidays. I preferred to be invited to the affairs of certain cousins or other acquaintances where there was always something savory, for example sandwiches with butter and anchovies or with cured ham, rosemary or onion pizza, and – in exceptional cases – the timeless butter and cucumber sandwiches of English ‘high tea’.

A dizzying choice..

If there were other children our age, mom seemed perpetually surprised at the racket we made, especially when my sister Sofia ran through the halls, and up and down the stairs, with other little girls in tow. Or if the noise of something being shattered ricocheted from the kitchen, she pretended nothing had happened, guessing that Rodolfo was again frequenting the pantry to sneak a few drinks from the bottles there. Mother would tower over guests strutting in her pleated plaid skirts in front of the fireplace or move about the room heedless of the fact that it had an air of perpetual metamorphosis and was never properly cleaned. When there were a lot of people, my grandmother would go and sit on the armrest of the sofa, something that would exasperate mother and twist her legs in a corkscrew fashion, something that would leave us stunned. After tea, the living room filled with cigarette and pipe smoke; it was, after all, an era when virtually everyone smoked, out of vice or affectation, and no one paid any attention to the non-smokers who were forced to inhale the fumes of tobacco mixed with chimney smoke. That was the time we kids would slip away. With all us siblings, plus our cousins and their squeamish city friends, we preferred more discreet, inconspicuous diversions, so we’d duck out of the house.

There was a neighboring property that was an irresistible attraction, despite being a ‘no-go’ zone. We’d rush down the hill and through the woods and climb over the gates. There in the valley bottom, a railroad ran through a row of fishponds, and if we could get there unseen by the keeper, a string of delights awaited us. A few old row boats were moored among the reeds, and it was enough to untie the ropes that held them to set off on an adventure. We’d paddle up and down the ponds, each connected by narrow canals crossed by pontoon walkways under which one had to duck one’s head. With luck we might catch the very instant one of the ancient regional trains chugged by, barely clanking along, reflecting its two melancholy carriages in the water. The pond reeds hid us from view from a small elevated road that ran along the perimeter of the marsh, and across it was a private game preserve whose owner kept, for his own amusement, llamas, camels, and large ostriches that roamed freely among his poplar grove. We could glimpse them from time to time, and it was fun to see the surprised faces of our guests who had never imagined we country kids could arrange a full-blown safari.

The irresistible lagoon

Despite our need to remain unseen, it was usually the girls who could not help externalizing their astonishment with excited shouts and screams. So that it was inevitable that sooner or later someone would notice us. Once alerted, the keeper called for reinforcements and they could be seen driving toward us, shouting menacingly and gesticulating from the car windows. As the landscape took on the rosy veil of evening mist – something akin to an Indian rice paddy – we’d have just enough time to tumble ashore, ditch the boats, and make a haphazard escape. Being chased provided our guests with an adrenaline rush and quickened heartbeats which spread a rosy blush on their pale city complexions. Back home, we’d find the adults stirring around the front door, our visitors long since ready to depart, with mother ushering them down the stone steps with much waving. It was not clear whether she intended to continue hugging them, or was impatient to see them off. ‘What in the world did you do to those poor girls?’ she’d ask casually at the lunch table the next day. But we all knew, even if they’d gone home stunned, they’d never had so much fun in their lives.

Awaiting guests at my home in France