By William Tyre

Frederic Clay Bartlett may not be a name that is instantly recognizable, but the artwork he created or collected helped establish Chicago as an important center for art in the first decades of the 20th century. The year 2023 marked the 150th anniversary of his birth, and the event brought together several scholars for a half-day symposium at Second Presbyterian Church, who discussed various aspects of his life, from his major mural commissions in the city to his advocacy for modern art, and from the significant collection of paintings he gave to the Art Institute of Chicago to his remarkable winter home, Bonnet House, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Frederic’s story begins in 1863 when his father, Adolphus Clay Bartlett, traveled from Stratford, New York, to Chicago at the age of 19 to clerk in a hardware firm. He was made a partner in 1877, and five years later, the firm reorganized as Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Co. It became one of the largest wholesale hardware firms in the country, and in 1904, Bartlett assumed the presidency after the death of William Hibbard. (The company was sold in 1962 for its “True Value” brand name, launching hundreds of retail hardware stores).

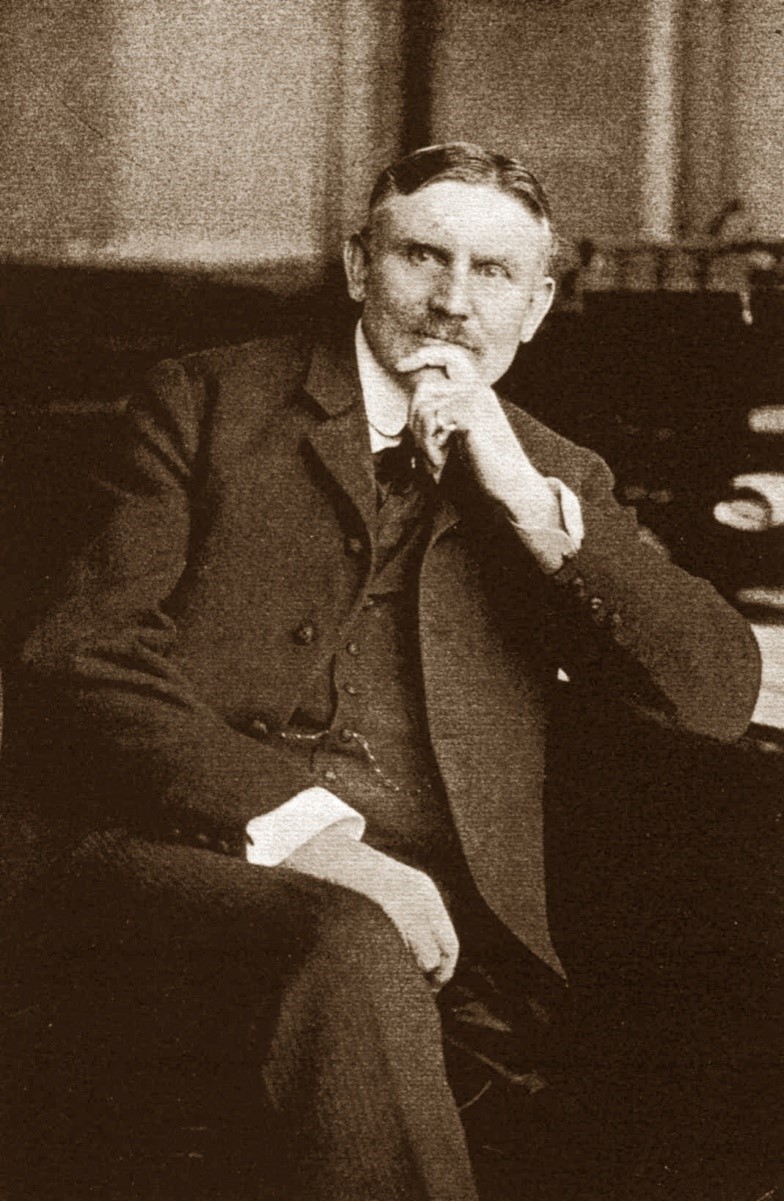

Frederic Clay Bartlett was born on June 1, 1873, at the family home at 31 Bryant Avenue on Chicago’s South Side. (The street no longer exists but was located between 35th and 36th streets, just east of Cottage Grove Avenue). When he was a young boy, his father purchased a new home at 2222 S. Calumet Avenue, placing them near the exclusive Prairie Avenue district and the homes of the Hibbard and Spencer families. Frederic attended the prestigious Harvard School for Boys, then located at Indiana Avenue and 21st Street.

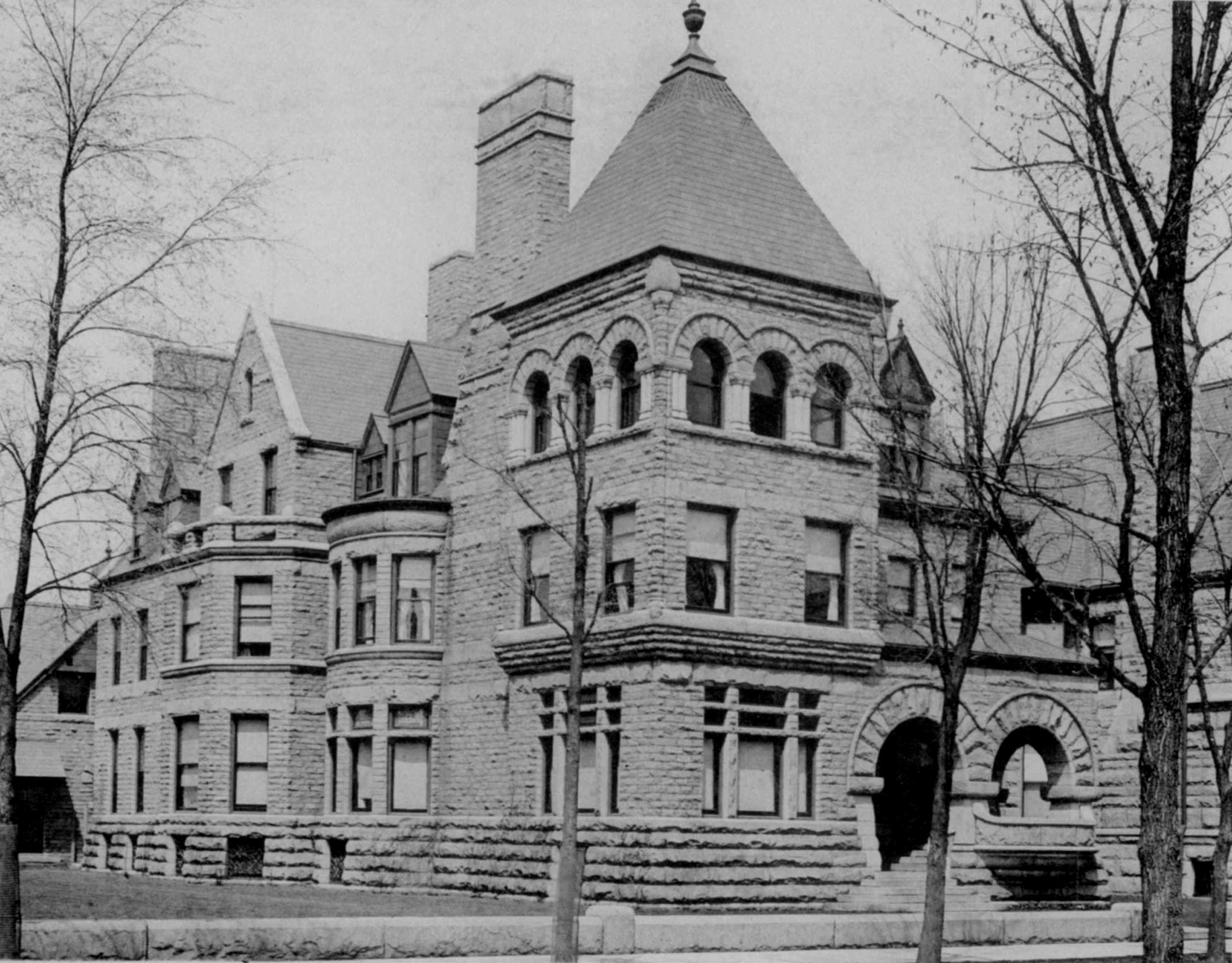

In 1886, the Bartletts commissioned Henry Ives Cobb to design a huge Richardsonian Romanesque home for them at 2720 S. Prairie Avenue. Two years later, Frederic was sent off to St. Paul’s School – an Episcopalian prep school in Concord, New Hampshire. He attended for two years before returning to Chicago in 1890 at the time of his mother’s death. It marked the end of his formal education.

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition marked a turning point in the young man’s life. He visited the Palace of Fine Arts countless times with his close friend and future art patron, Robert Allerton. Together, they studied one of the largest collections of paintings ever assembled in the world. Frederic later wrote:

“Tired we were, for as was our custom, we had walked past miles and miles of pictures, a never-ending wild excitement for us. To think that men could conceive such things, and actually bring them into being on a flat bare canvas. . . We pledge our lives to the creation of beauty and forthwith determined to leave the security and luxury of home, and at nineteen to forge out into the world, to learn the technique, secrets, and methods of artists.”

In 1894, Frederic was accepted into the Royal Academy in Munich, one of the first Americans admitted into the school. He excelled and won numerous awards by the time of his graduation two years later. He traveled to Paris, where he had the opportunity to study with the leading French muralist of the day, Paul Puvis de Chavannes. He also spent time in the studio of James McNeill Whistler, the American expat artist then living in Paris.

Bartlett married fellow artist Dora Tripp in 1898, and they set up housekeeping in Munich. His brother Frank died during a visit there in 1900, and they accompanied the body back to Chicago for burial, deciding to make the city their permanent home. Frederic leased space on the 10th floor of the new Fine Arts Building, and his long-time friend, architect Howard Van Doren Shaw, designed the studio. The studio placed him in the creative center of Chicago, with other studios occupied by sculptor Lorado Taft, political cartoonist John McCutcheon, commercial artist Joseph C. Leyendecker (creator of numerous Saturday Evening Post covers), and artist William W. Denslow, who illustrated The Wizard of Oz.

Between 1900 and 1910, several of the Fine Arts artists collaborated on the mural decoration of the 10th floor of the building. Frederic’s contribution was “Woman and Angels,” completed in 1910, which has been restored in recent years, as seen above. It is a self-portrait, with Bartlett shown as a Renaissance artist at right, standing on scaffolding. He is undertaking a large mural of angels, as seen at the center of the mural. At right, his live subject is richly robed in red and holds a bowl of flowers in front of a gold backdrop.

The depiction was appropriate, as Bartlett’s first large-scale commission, received in 1900, was for a series of thirteen pre-Raphaelite-inspired murals for Second Presbyterian Church, located at 1936 S. Michigan Avenue. The church suffered a devastating fire in March 1900, which destroyed the sanctuary and roof but left the exterior walls intact. Howard Van Doren Shaw was commissioned to rebuild the sanctuary and engaged his friend to undertake the interior decoration. The major unifying theme of the new space, designed in a blend of English and American Arts & Crafts, was the angel, of which 175 adorn the space, with dozens appearing in Bartlett’s murals.

Bartlett’s decoration of the sanctuary, which was completed in late 1901, was extensively covered in a 1904 article in House Beautiful which noted, in part:

“If you have spent hours in the dim old churches of Padua and Florence studying faded frescoes, you will feel very much at home in the recessed windows of this Chicago church. Not that the decorations are copies – not that they are in any sense an imitation of the work of the early Italians – for they are full of Mr. Bartlett’s individuality – but the spirit of the old frescoes has been seized and perpetuated. The colors are few, the tones are flat. The figures have the slender stiffness that Cimabue and his pupil Giotto painted into their pictures.”

Twelve murals are set into the side arches over the leaded glass windows. Each of these was painted on canvas and then attached to the wall. Beneath each, scriptural passages are painted directly onto the plaster. The three themes of the murals alternate between angels praising God, performing sacred music, and celebrating the abundance of the harvest. Bartlett’s original color scheme can be seen in the right and bottom portions of the image above, which shows a partially restored arch mural. Friends of Historic Second Church, a non-profit preservation-based organization founded in 2006, has overseen the restoration of several Bartlett murals in this National Historic Landmark interior.

The largest mural, completed in 1903 and known as the “Tree of Life” was completely restored in late 2022 in a project funded partly by a Save America’s Treasures grant, which covered just over half of the $500,000 cost. The work, which also included the four life-size heralding angels and other features on the front wall of the sanctuary, was undertaken by Chicago-based Parma Conservation. Their meticulous work revealed Bartlett’s original artistic intent through the restoration of features such as the beautiful angel faces, the re-emergence of the rich color scheme, and the repair of the gilded bas-relief outlines of the angels’ halos and wings.

The project at Second Presbyterian led to several other church commissions, including, most significantly, Fourth Presbyterian Church, completed in 1914 on North Michigan Avenue at Delaware Place. This was another collaboration with Howard Van Doren Shaw, along with architect Ralph Adams Cram. Bartlett created an extensive decorative program for the sanctuary, including the decoration of fourteen life-sized angels, most of which are depicted playing musical instruments, and dozens of mural panels set into the arches of the side aisles. The murals were recently restored by Parma Conservation, revealing an especially rich color palette accented with gold.

Another surviving mural commission can be found in the entry of the Bartlett Gymnasium on the campus of the University of Chicago. The building, donated by Adolphus Clay Bartlett in memory of his son Frank, was designed by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, who worked closely with Frederic to blend the Gothic and English Arts & Crafts styles. Bartlett designed the large leaded glass window on the front façade, his first venture into that medium. (It was removed several years ago and sits in storage awaiting restoration). His mural spans the full width of the main entry hall and was appropriately named “Athletic Games in the Middle Ages.” The colors are more vibrant than his church commissions, an article of the time notes:

“The colors are brilliant, often crude, and wholly Gothic, but so skillfully are they blended to form a harmony of color that is a joy to the eye and an inspiration to the mind.”

Bartlett’s largest commission was the extensive decoration of the University Club at the northwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Monroe Street, designed in 1908 by architects Holabird and Roche. For the second-floor dining room known as the “Michigan Room,” Bartlett executed 56 large ceiling panels depicting the phases of a Gothic chase and feast.

Bartlett also submitted plans for the enormous windows on the 10th floor of Cathedral Hall, with intricate designs designating universities around the world and various disciplines. Louis Comfort Tiffany also submitted plans. According to the official history of the Club, once Tiffany became aware of Bartlett’s plan, he withdrew, noting:

“The reason is that my sketches are unworthy to be seen in the presence of the most beautiful, most fitting, most remarkable stained-glass windows done in modern times, as designed by your fellow member, Frederic C. Bartlett!”

Holabird and Roche returned to Bartlett in 1911 when they received the commission for the new City Hall. Bartlett designed eleven murals for the City Council chambers, measuring nine feet in height, to “typify the active, energetic, democratic spirit of Chicago.” Subjects were treated symbolically, not historically, and included law, order, commerce, labor, justice, truth, education, construction, electricity, and the gifts of Illinois to the nation. The final mural was entitled “Havoc of the Great Chicago Fire and Aid of the Sister Cities.” Ironically, that mural and all the others were completely destroyed in 1957 when fire gutted the chambers.

Bartlett’s wife died unexpectedly in March 1917 at the age of 37. Two years later, he married long-time family friend Helen Birch. Her father, Hugh, a successful attorney, had purchased huge tracts of undeveloped land in Florida, where the city of Fort Lauderdale is now located. He gifted the couple 35 acres of oceanfront property where they constructed their winter home, named Bonnet House, after the bonnet lilies that grew on the property. The house was designed by Frederic, who continued to improve it for the remainder of his life. The property now operates as a historic house museum and is open to the public.

Frederic and Helen traveled widely and began amassing an important collection of post-Impressionist paintings. When she died in 1925, she willed the collection to the Art Institute, which at first hesitated to accept the paintings, thinking visitors would not be interested in the modern works of art. But the collection proved to be among the most important ever gifted to the museum. It contained their first Picasso, Van Gogh, Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec, and most importantly, Georges Seurat’s iconic A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884, perhaps the Art Institute’s most recognizable work. Following Frederic’s death, Daniel Catton Rich, the director of the Art Institute, noted:

“He was one of America’s first collectors to buy great post-impressionist paintings. . . Frederic Bartlett was talented as a painter and it was with a painter’s eye that he judged the great French art of this period. He and his wife, Helen Birch, built up a collection of remarkable quality . . . This became the first room of modern art in any American museum . . . It remains as a monument to its generous collector, the rare example of a group of paintings gathered with deep knowledge, taste, and warm understanding.”

In 1931, Frederic married Evelyn Fortune Lilly, also an artist. Although Frederic did not complete any mural commissions after this time, he continued to actively easel paint for the remainder of his life. The couple divided their time between a summer home in Beverly, Massachusetts, and Bonnet House. He died on June 25, 1953, and was buried beside his first two wives in the family plot at Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery. Evelyn joined him there in 1997, after her death at the age of 109.

Today, Frederic Clay Bartlett’s surviving works at Second and Fourth Presbyterian churches, the University Club, and other locations, along with his incredible collection of post-Impressionist paintings at the Art Institute, serve as a fitting tribute to this gifted and visionary artist who left his mark on the artistic and cultural landscape of the City of Chicago.

To learn more about the work of Friends of Historic Second Church and to confirm the schedule of free sanctuary tours, visit historicsecondchurch.org.