By Cheryl Anderson

“Knotted, stretched, twisted, folded, pleated, rolled or rumpled, its silk expressive, its colours alive.” Nadine Coleno.

“Knotted, stretched, twisted, folded, pleated, rolled or rumpled, its silk expressive, its colours alive.” Nadine Coleno.

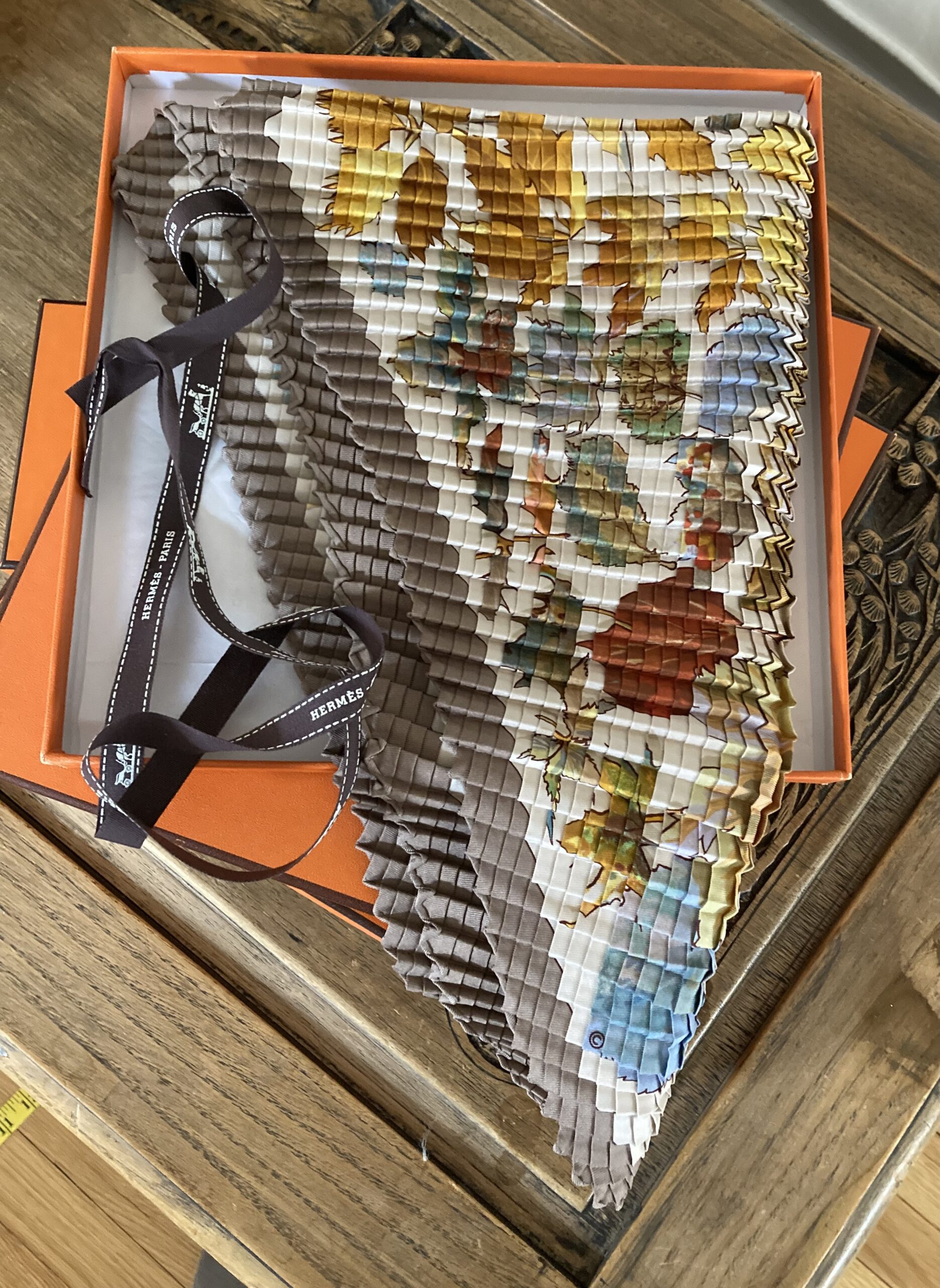

Anticipation runs high as the orange Hermès box sits in your lap. It’s tied with a narrow brown ribbon, the embossed white horse and buggy gallop between white lines that look like stitches. You pull the ribbon and lift the lid, gently turning back the tissue and there, neatly folded, a carré de soie like no other. It’s Hermès. Laying it out flat, you wonder what is its story—there’s a meaning behind the design and its name, every scarf has one, is incorporated in the design. Sometimes, the name is cleverly hidden when other times it’s boldly clear. I had to look closely to find the complete name in, Hermès at the beach.

As it slides through your hands, you sense the subtle richness of the silk, and oh, how beautiful, the luscious colours, also with their own names unique to Hermès. You will keep it forever and enjoy thinking of clever ways to wear it again and again.

“The Hermès silk scarf has a thousand secrets and deploys them like a subtle strategist. It is fun-loving, the resolute enemy of monotony. It tells stories, invents, challenges and readily overturns its own rules, which is a sure-fire safeguard against growing old.”

At a time, when the 1920s had been filled with the glorious parties and frivolity, and after the tragic financial crash in 1929, only to be followed by the horrors of war, “The Hermès scarf was born into a world that was crying out for new dreams.” The year of its launch was 1937—the company turned 100 that year.

|

|

|

That same year, 1937, the International Exhibition of Art and Technology was held in Paris—31 million people from all economic classes would attend. This exhibition showed the world innovations in utility and beauty, the same philosophy held by the House of Hermès.

Robert Dumas, (Émile Hermès’ son-in-law), together with his son, Jean-Louis, designers, engravers, colourists and screen printers created, or as Jean-Louis puts it, “invented”, the Hermès scarf—le carré de soie, “an accessory that has become a landmark in the history of style.” Their enthusiasm, passion, and determination won the day. Pierre-Alexis Dumas states, proving the aphorism, “They didn’t know it was impossible, so they did it.” And, he further encourages for all to remember, “it all began as a game.”

The board game, Jeu des Omnibus et Dames Blanches, was very popular in the 1830s. One of these games was among the vast collection of objects Émile Hermès had amassed—starting at a very young age, he spent “his modest spending money on objects whose value lay in their history or functionality.” (This collection will play an important part in future scarf designs.) But, for now, the board game is what inspired the first design, for the first scarf presented in 1937. Competition between two Parisian transport companies that ran omnibus carriages between Bastille and Madeleine is what prompted the creation of the game. One company was named, or called, les Omnibus, and the other, les Dames Blanches.

Jeu des Omnibus et Dames Blanches

Original colors for Jeu des Omnibus et Dames Blanches

In the center of the scarf, within a circle, ladies and gentlemen are seated in fashionable attire playing the game, while around the center are two circles of racing omnibus carriages. The name of the game is the name of the scarf. You’ll find it written along the top edge of the center circle above the players and below the players along the outer edge of the circle are the words, (in French), “A good player never loses his temper.”

As with everything Hermès, quality and detail matter—both elements are always perfect. The hem of each scarf is hand-stitched. I once viewed a short video on the construction of the Birkin handbag. Hermès’ extraordinary craftsmanship at its finest was on display. The same care goes into every carré de soie.

Pleated is very pretty.

Why the square, le carré? Nadine Coleno says, “The square is perfect, stable, simple and evenly proportioned, and lends itself to endless transformations—all qualities that have given it symbolic power since the dawn of time.” She goes on to mention origami and furoshiki, the Japanese form of wrapping. The same word identifies the square cloth. I still have my furoshiki and remember well wrapping my books to carry them to school when I lived in Japan.

My furoshiki.

Squares of fabric were used by the men in ancient Greece and Rome to wipe their faces. In the 16th century, pretty squares of fabric were given to women as tokens of love, and in the 17th century “snuff lovers appropriated them.” Nadine Coleno gives quite a few more examples of how the square has been used throughout history. I have handkerchiefs from when I was a child, always had one in my purse, and ones from my aunt, grandmother, and as mother-of-the-bride. Pretty little squares that hold memories. “This regard for history and flexibility of use are qualities that have always been shared by the Hermès scarf.”

Le carré de soie Hermès, comes in various sizes; from pocket squares in silk twill and pongee silk, to 45, 60, 70, 90 centimeters. Each design motif comes in different color-ways to choose from thus changing the visual character of the design. And, quite often there is one color-way that speaks right up, the one you want the most.

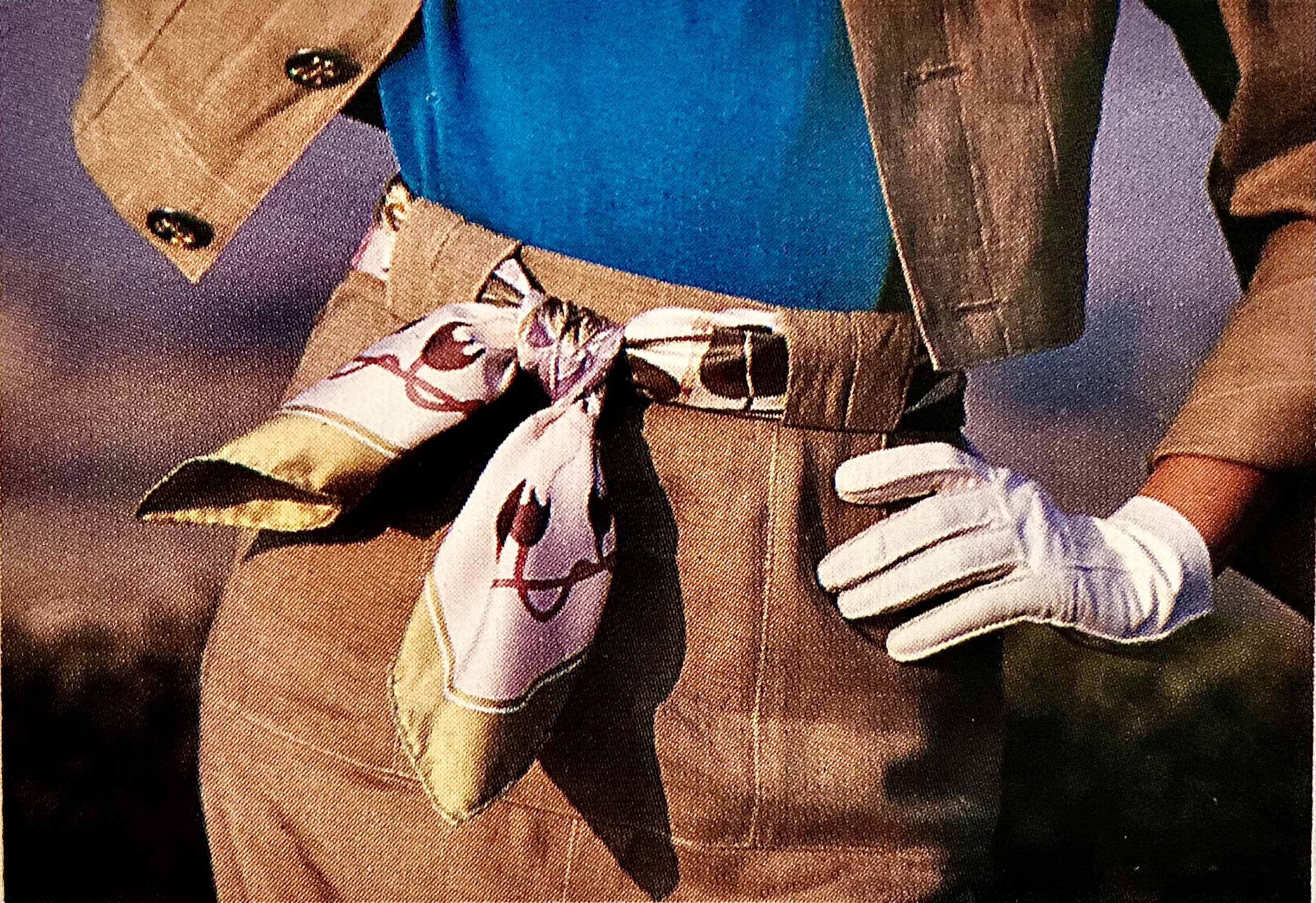

You’ll find a use for every one of the sizes. The 40s are perfect for wrapping around your wrist or around your neck for a jaunty look with a crisp white shirt or sweater. Tuck one in a pocket for a pop of color, or tie one on the handle of your handbag, that little touch adds personality—so fun. Once, at the Hermès store in Monaco, I watched as the handle of a customer’s Hermès handbag was wrapped with a scarf—the chosen scarf was perfect with the color of the handbag. Round and round it went and when it was all done, the ends of the scarf looked like little wings. The young lady made it look easy to do, but I dare say it takes a lot of practice. However, you choose to wear or use, le carré de soie Hermès, as Pierre-Alexis Dumas puts it, has “become a landmark in the history of style.”, so you cannot go wrong.

|

|

|

|

In a small Hermès publication, I saved from many years ago, How to Wear your HERMÈS scarf”, there is a line on page 22 with the Sextants scarf: “Faded jeans and an Hermès carré—what could be more right?” My thought exactly. They are to be worn and enjoyed. Rolled and slipped through belt loops and tied around your waist, tied into a bow around your neck, or into a series of knots, Hermès calls them “silk pearls.” Written at the top of page 18 is Monte Carlo. The Napoléon is used for a strapless top. Monte Carlo is perhaps where you might see an Hermès scarf worn just that way.

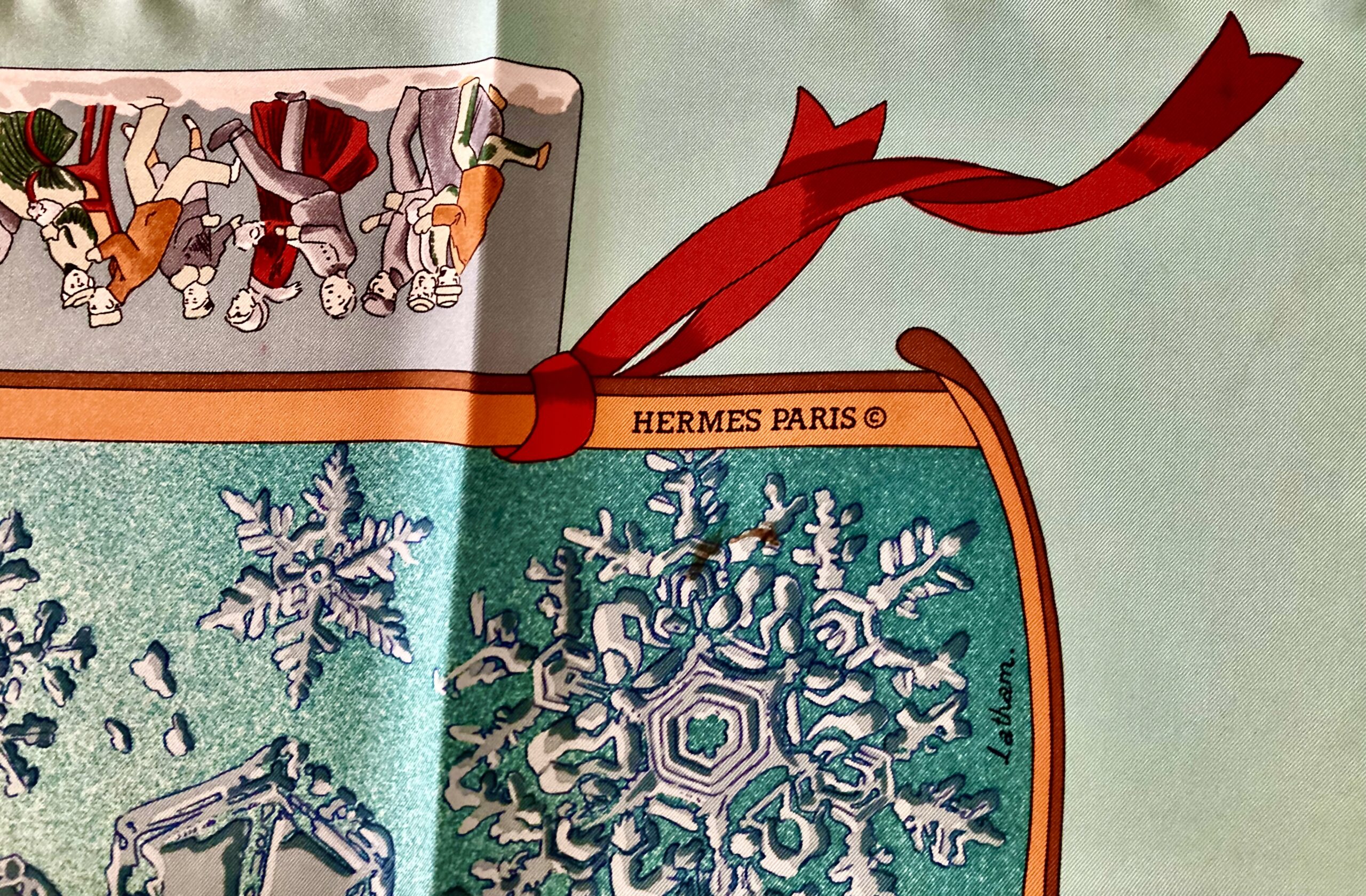

Remembering snow of yesteryear. |

xxxxxxx |

|

|

|

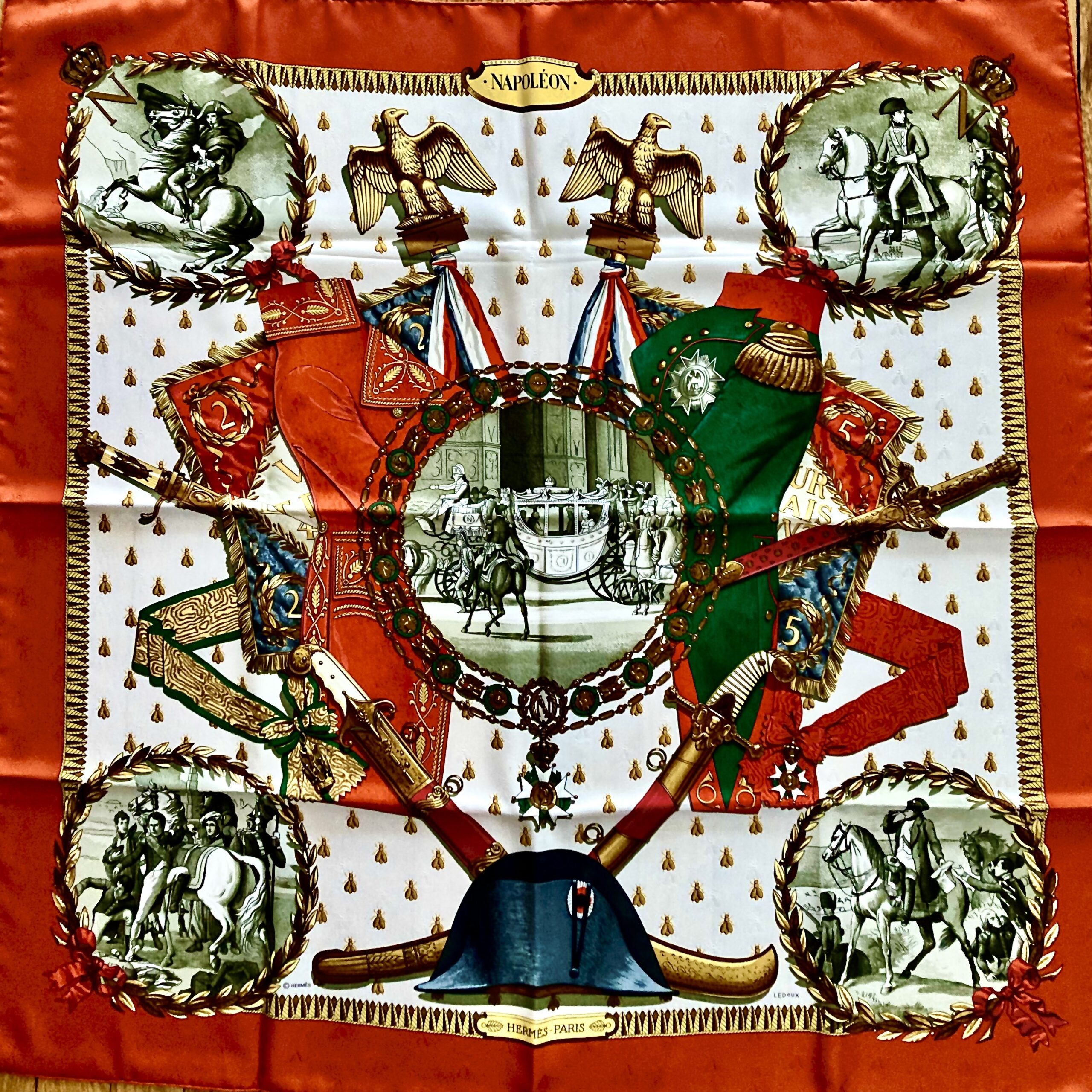

An Hermès scarf is easily identified, even from a distance, the colours, and perhaps a bit of the motif gives it away. “I love your scarf”, words spoken to me recently. I was wearing the, Napoléon, in orange—it’s delicious in a heavenly pink. My mother wore the pink with her pale pink cashmere sweater set and pearls—it suited her perfectly.

The Napoléon in orange. |

ccccccccc |

In the weeks to come, I will tell the stories behind specific scarves—from the one Collette wore as a bow-tie to those carrés with motifs relating to Èmile’s object collection. I’ll share pictures from HERMÈS POP-UP, (a delightfully fun little book), the stories behind designers of the scarves that are considered Hermès classics, and others of course, and a bit of the history of the House of Hermès and some of what they have created over the decades. They began with “made to measure” saddles and harnesses, but as we know their passion for quality, functionality, and beauty has led to so much more.

Recognizing, it’s Valentine’s weekend, I leave you, for now, with two images…Brides de Gala Love and Brides Fleuries. Hearts and Flowers from Hermès.

|

|

À bientôt

Quotes and Pictures

Little Book of HERMÈS The story of the iconic fashion house, by Karen Homer, publisher Welbeck, 2022

The Hermès Scarf—History & Mystique, by Nadine Coleno, Thames and Hudson, publisher.

Hermès publications.