A chilly Chicago afternoon, set the mood to read some poetry. So a trip to the Pilsen Community Books was the way to go, with the hopes of finding some local authors to read from…thanks to the help from the friendly staff, they recommend the works of Eve L. Ewing; “1919” is a collection of poems that explores The Chicago Race Riots of 1919. Truly an illuminating read that evokes a sentiment to those whose life was lost and to the ones who suffered from the hands of the hatful mobs. The riots lasted all summer and across major cities in the nation, it was coined as The Red Summer of 1919. After reading the book, it sparked an interest to learn more about the 1919 riots and other historical events that occurred in Chicago. That interest instinctively guided me to a trip to the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center, it seemed relevant to explore more about black causes and topics with Black history month approaching.

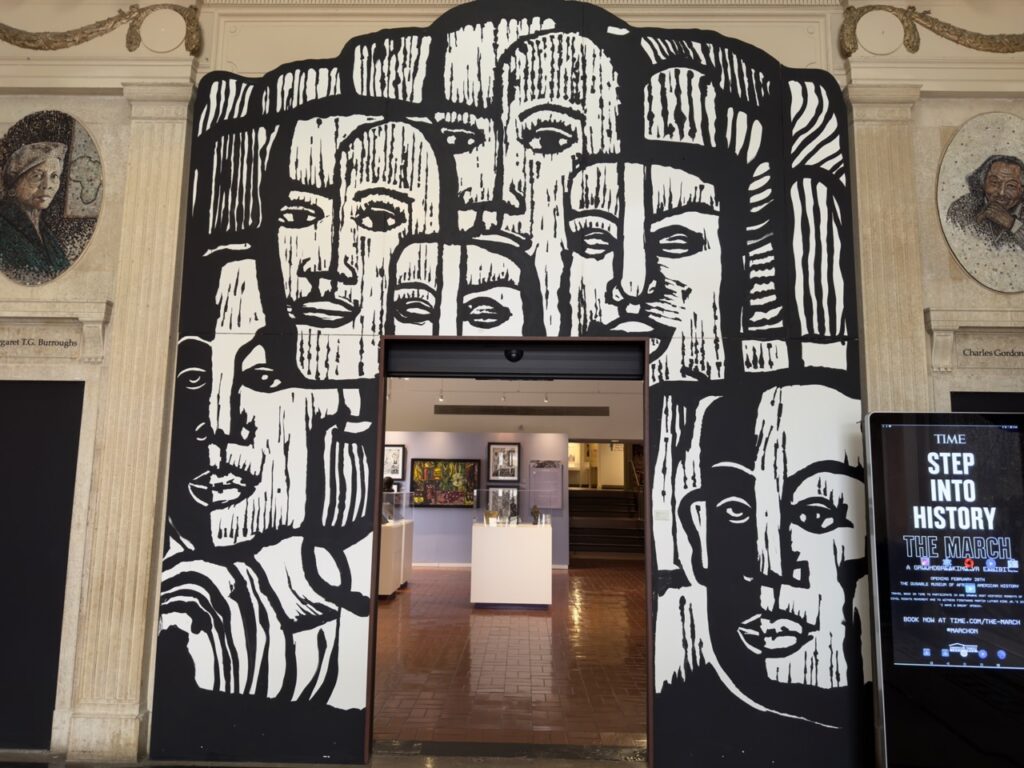

Upon entering, you’re greeted and given an overview on the new exhibit; a timed-entry pass to THE MARCH, a virtual reality experience that transports you to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C., to witness Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech. A sincerely captivating demonstration of what it would have been like to march alongside Dr. King, gaining the ability to view his renowned speech only steps away from the podium.

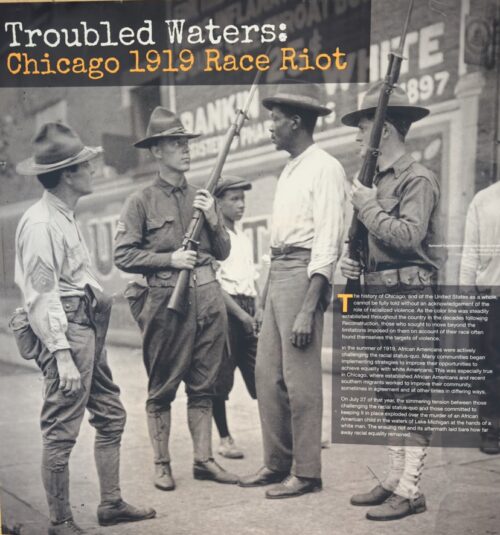

THE MARCH resonates some familiar tones that is still prevalent to Black people in America, a repetition of a fight against discrimination and systemic racism. It was the pillars of white supremacy that ignited the race riots of 1919, in a deeply segregated Chicago, The Red Summer of 1919 is the origin story of how Chicago became what it is today.

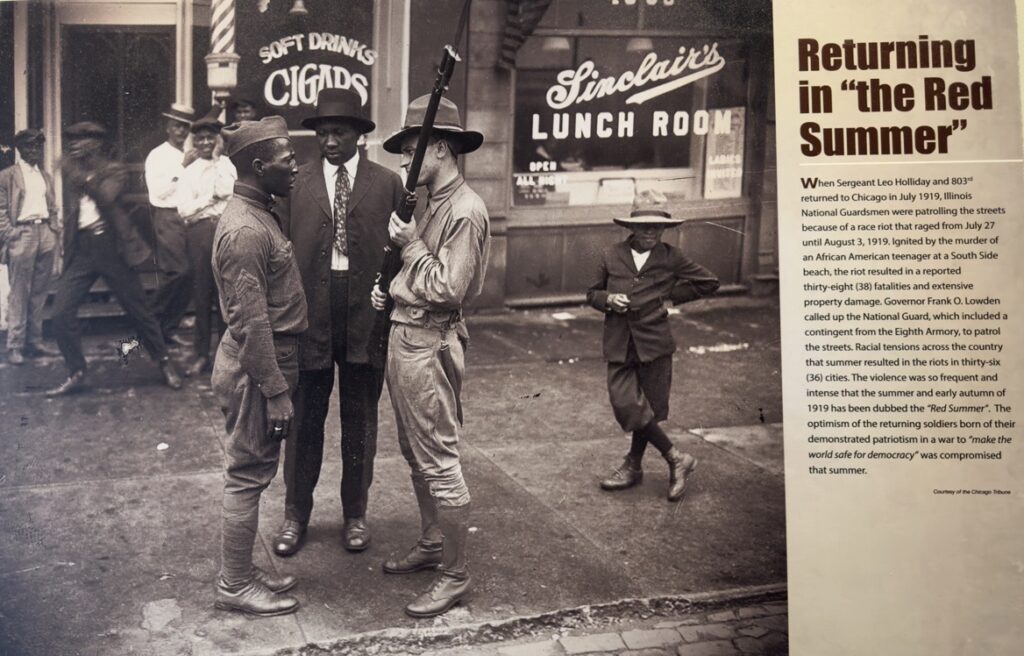

Black soldiers returning home and ordered to patrol the streets with high racial tensions, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

Map of incidents of racialized violence that occurred during the Red Summer of 1919, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

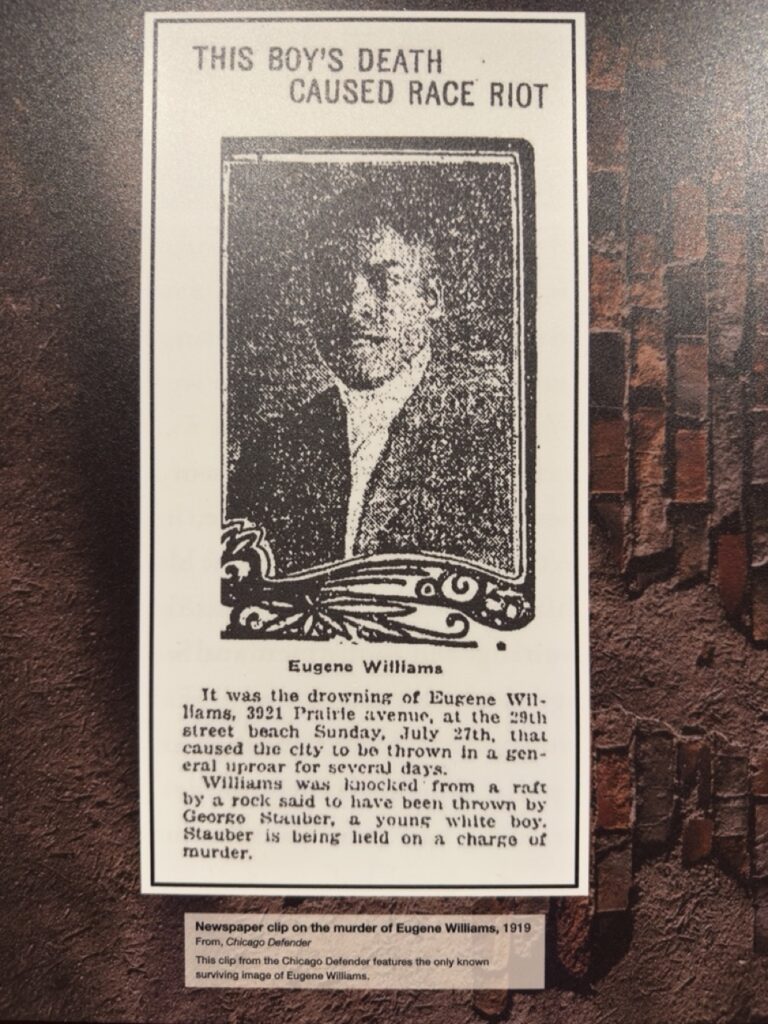

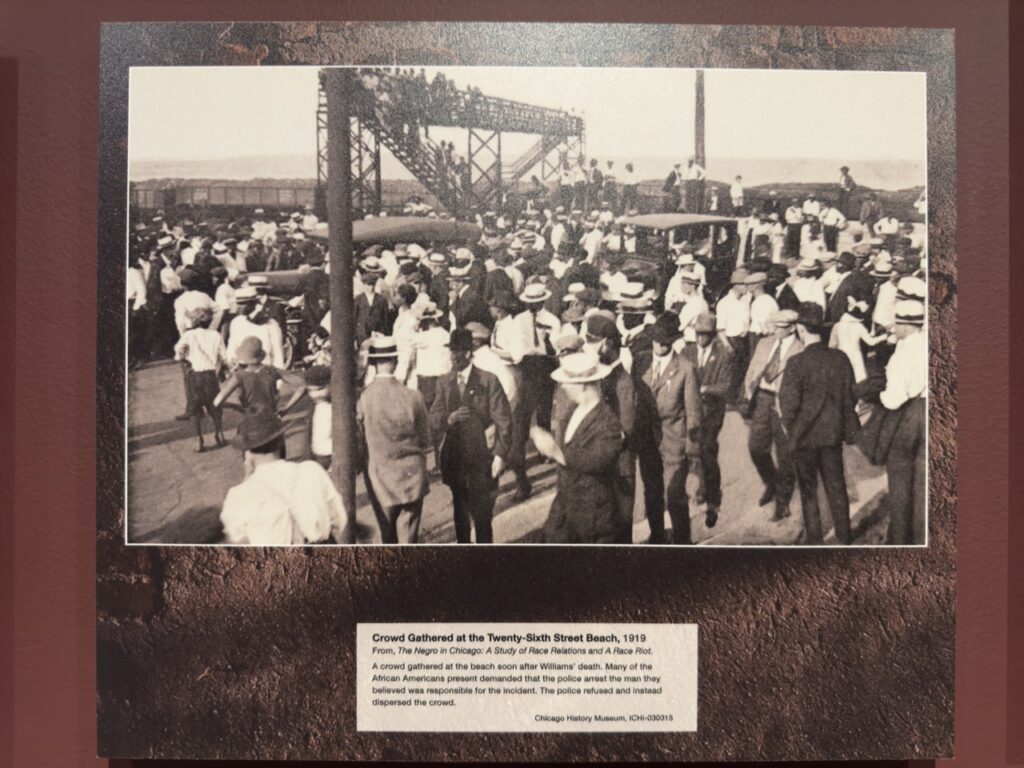

July 27, 1919 was a scorching day in Chicago. That’s when young seventeen-year-old Eugene Williams went to cool off at Lake Michigan with some friends. The boys playing in the water with their floating devices unintentionally floated past the invisible line and into the whites-only side of the beach, sometimes the line was referred to as the “Deadline” that kept both races separated. A group of whites nearby noticed and became aggressively hostile towards the kids, they began throwing rocks at them, striking Williams, causing him to drown. His murder sparked outrage in the Black community, demanding the police arrest the killers…but the police refused, causing tensions to sharply increase.

Newspaper clip on the murder of Eugene Williams, 1919, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

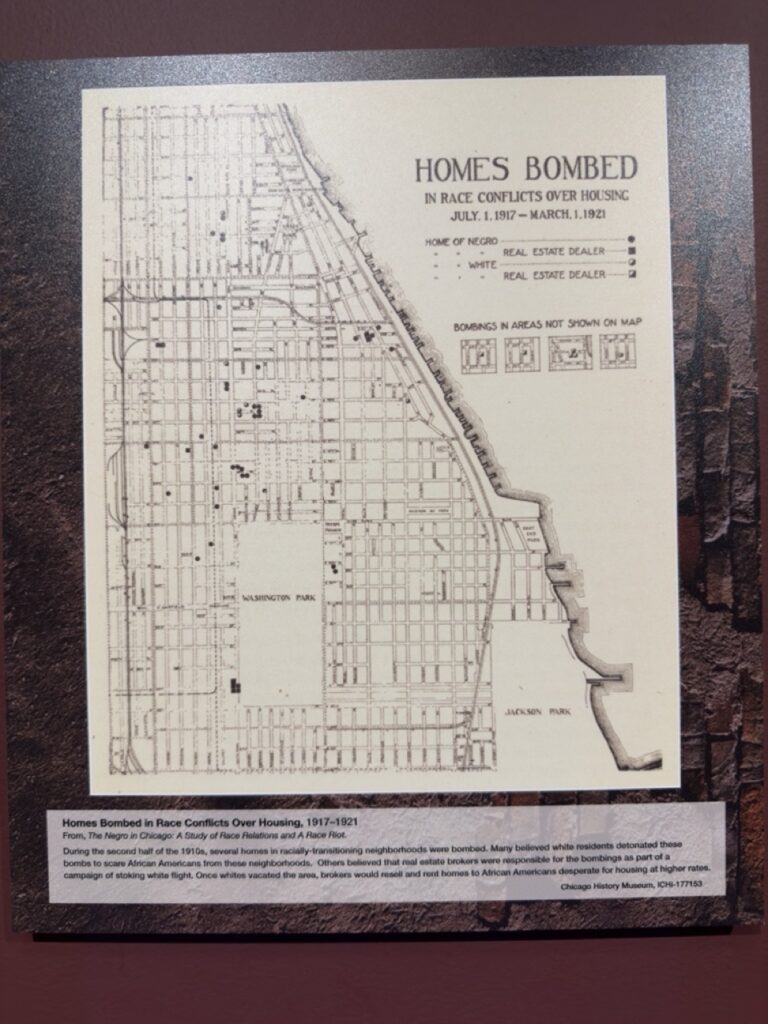

Homes bombed in race conflicts over housing, 1917-1921, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

Rioting broke out across Chicago’s West and South sides and in the downtown areas, lasting days before the military began deploying troops to restore order. The riots lasted about seven days; the resulting fighting, shooting, arson, and looting led to the deaths of 15 whites and 23 black people. Records are difficult to say exactly how many people were injured and many more were forced to flee their homes from a lack of proper documentation. Racial violence kept occurring during the summer of 1919 in other major cities across the nation.

Crowd gathered at the Twenty-Sixth street beach, 1919, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

Police attend to man lying on ground, 1919, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

The riots left a legacy of challenging racism and the social hypocrisy that failed to bring Eugene Williams’s killers to justice. The Red Summer left an impression on the Black community where the intimidation of the police and military force, as well the white mobs who contributed, couldn’t quell the voices of the Black community and letting themselves go calmly into compliance at hands of the oppressors. Activism rose prominently in the days to come, but racial violence against the black community greatly increased as well, up to post World War II. Serving as a fundamental framework for the civil rights movement and The Civil Rights Act of 1964.

National guardsmen stand watch on unidentified street corner, 1919, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

Building destroyed by fire during the riot, 1919, courtesy of The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center |

The Red Summer of 1919 has plenty of untold stories that couldn’t fit in this article. I implore readers to visit The DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center, before THE MARCH event ends, visit Dusablemuseum.org for more information. The works of Eve L. Ewing is also highly recommended, her other works include “Ghosts in the Schoolyard” and “Maya and the Robot” to name a few, she also writes comic books which include “Ironheart” and “Black Panther,” visit Eveewing.com for more information about her and her work.

References:

Red Summer. National WWI Museum and Memorial. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/red-summer

Troubled waters: Chicago 1919 race riot. DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center. (2021, March 22). Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.dusablemuseum.org/exhibition/troubled waters-chicago-1919-race-riot/