By David A. F. Sweet

When Bryan Gruley worked in the Washington bureau of The Wall Street Journal, the morning staff meeting would occasionally include a guest speaker. One week, the invitee was James Berger, former President Clinton’s State Department expert on terrorism.

The meeting never happened. Instead of hearing about terrorism, Gruley covered it on Sept. 11, 2001.

“It was a terrible day, but you’re trained as a journalist to respond to that,” says Bryan Gruley about 9/11.

Because the Journal’s New York office was across the street from the World Trade Center, it was nearly impossible to get hold of anyone there that morning. As the stunning day progressed, Washington Bureau Chief Alan Murray told Gruley: You need to write a story for The Wall Street Journal Europe, whose deadline was approaching.

“It was based mainly on other reports,” recalled Gruley, a former Chicago resident who served as the Journal’s bureau chief in the Windy City. “Then he said, ‘No one in New York is able to do this today. You have to write the main news story for the (U.S.) paper.’”

Tasked with the biggest news piece since Pearl Harbor was bombed 60 years earlier, Gruley soon started receiving e-mails from reporters in New York, saying they were OK and asking how could they help.

Gruley’s writeup of the devastation appeared on the front page of the Sept. 12, 2001 Wall Street Journal.

Gruley crafted a 3,000-word piece from reports from not only New York but Boston and other spots that was e-mailed to the editors who had gathered during the emergency at the Journal’s news operation in South Brunswick, N.J. by 6 p.m. The next morning, it appeared in the Journal’s lead column on the left-hand side of the front page.

“It was a terrible day, but you’re trained as a journalist to respond to that,” Gruley said. “When I think of that day, I think of my colleagues in New York who risked their lives to cover this story. They did what they had to do to tell the world what happened.” The next year, Gruley was among a number of Journal colleagues who received the Pulitzer Prize for their coverage.

As a boy growing up in Detroit, Gruley knew he wanted to write. He worked for his high school paper and then The Observer at the University of Notre Dame. The summer after he graduated in 1979, he borrowed a book on newswriting from the Wayne State Library. He also read David Halberstam’s tome The Powers That Be, a broad look at the rise of Time, CBS and other media powerhouses of the 20th century.

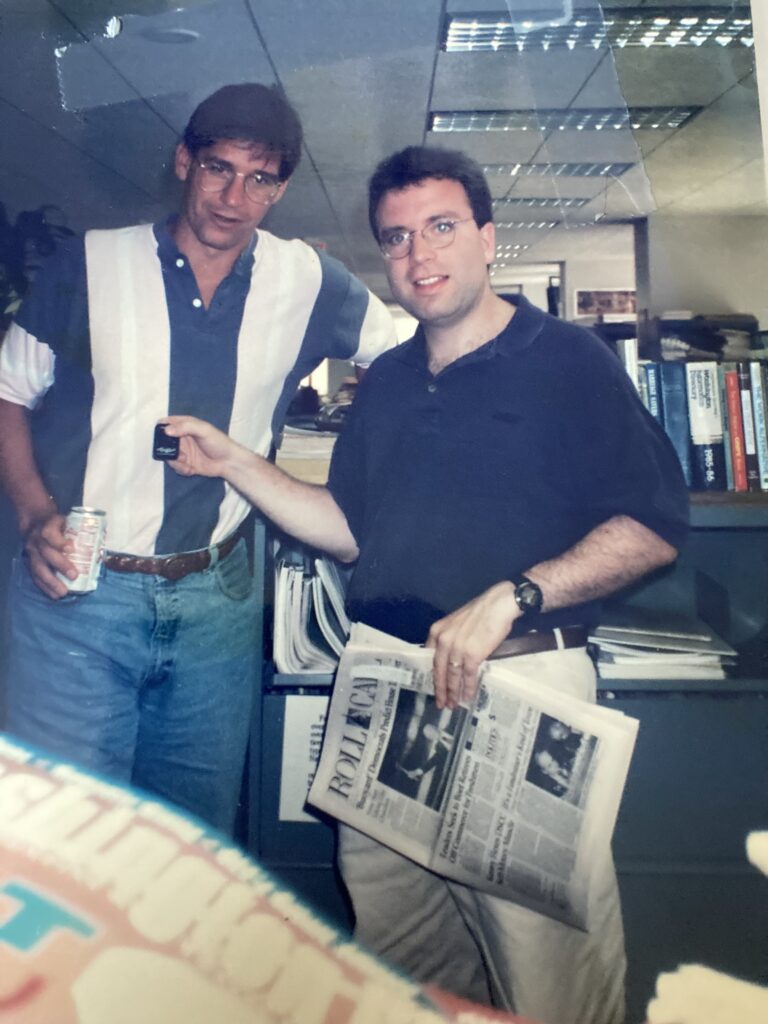

“It was a place filled with laughter and passion and soul,” says Gruley (left, with Dana Millbank) of his time working in WSJ’s Washington Bureau.

Working on a weekly in the Detroit area, Gruley was enlisted in many roles, as is typical on those all-hands-on-deck papers: he covered the school and the cops, wrote headlines, laid out pages and more.

“I did everything but sell ads,” he recalled.

Then, he joined the Detroit News to cover the auto industry. In 1987, the paper sent him to Washington, where he competed against reporters from the Journal and The New York Times. His legwork captured the Journal’s attention.

“There was one ongoing story about GM and trucks they had where people died when they exploded,” said Gruley, referring to the defective gas tank in models that ended up killing more than 2,000 people. “A number of times the Journal had to chase my stories, and they got tired of that.”

Soon after joining WSJ in the 1990s, he added telecom to his automotive-industry duties. Given that Congress had recently passed a large telecom deregulation bill, Gruley had plenty to write about and crafted many page-one stories. His time working in the D.C. Bureau was a highlight of his career.

“It was a place filled with passion and laughter and soul,” he said. “And no small amount of talent.”

Despite Gruley’s happiness with his workplace, a top editor, Dan Hertzberg, periodically tried to persuade him to serve as a bureau chief in other cities. With his children still in school, the reporter expressed no interest. But once Gruley’s youngest graduated from high school, Hertzberg said, “It’s time to make your next move.”

The Chicago bureau chief job opened up in 2005. Gruley took it.

“What a great city, and I had great people working for me,” Gruley recalled. “We covered things people understood – airlines, agriculture, real things. New York sneered at me when I suggested covering the Chicago Board of Trade and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

“I played a lot of hockey in Chicago. I’ve written plenty of stories about hockey and got a number of them in the Journal, which I think is a great accomplishment.”

While running the bureau, Gruley wrote mystery/thriller novels set in northern Michigan. Given his background, it’s no surprise journalism is a thread among them. Published by Simon & Schuster, the first three are narrated by small-town journalist Gus Carpenter. The next two – published by Amazon’s Thomas & Mercer imprint – feature important characters who are journalists.

What does he like to write better: fiction or non-fiction?

“In both cases, I love tales,” Gruley said. “Fiction is just a different challenge. Non-fiction, you usually know how the story ends. You have this pile of clay and sculpt it down. With fiction, it’s mostly your imagination, and that’s limitless. The main challenge is keeping the reader in the room.”

Now living on the west coast of Florida (“except for the tense moments around hurricanes, it’s great”) Gruley has not forgotten his non-fiction roots. In October, he penned a widely read piece for the Journal’s Weekend Edition entitled The Great Notre Dame Keg Caper. During a 1977 football game, students tried to hoist a keg into the dry stadium.

“I was at the game where these knuckleheads tried to sneak the keg in, but I didn’t know about it at the time,” Gruley said. “Years later I got to be friends with the mastermind of the plot, Jerry Castellini. Jerry told me the story a couple of years ago, and he wanted me to write it.

“I said, ‘Who’s going to read it?’ But he kept bugging me.”

As Gruley reported in the Journal last month, “Obstacles were considerable. Full kegs weigh 80 pounds or more and can’t be stowed in someone’s puffy winter coat.” Despite an initial rebuff by an usher who confiscated Castellini’s rope inside the stadium, after halftime the keg was pulled up the wall and into the stadium. Not only were fans happy; Notre Dame player Bob Golic drank an Old Style from the keg on the sidelines.

Now in his mid-60s, will Gruley keep writing or retire from the craft for other pursuits? Said he, “I don’t know how to do anything but write. I will write.”

Unsung Gems columnist David A. F. Sweet is the author of Three Seconds in Munich. He can be reached at dafsweet@aol.com.