BY KATIE FREIBURGER

There is one question that has remained steady throughout my years living in Chicago: “Why here, when you were raised in California?”

In reality, we have contemplated moving back to Pasadena so often that we have exhausted our friends and family with the topic. Despite all of our hemming and hawing, staying here feels right and, after 25 years of winter, I will readily admit my true love for the first snow.

And we are certainly not the first to build a proverbial bridge between Chicago and Pasadena. Growing up, neighbors and friends in Pasadena always had a preoccupation with our hometown’s Midwestern roots. I would hear the banter but never stopped my carefree days to study the history. Beyond the obvious connections, such as the Wrigley Mansion (present-day home to the Tournament of Roses), I often wondered to what everyone was referring. So, this past Summer, I decided to research these mythical connections and discovered that the influence of Chicago is everywhere in Pasadena.

Beautiful, serene, and famous for Caltech, the Tournament of Roses, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena also holds a rich and impressive history, which (after much digging) can be attributed to some of Chicago’s leading families. The breadth of names on the list of individuals who made their way from the Windy City to Pasadena at the turn of the last century is remarkable; more impressive is what that small but mighty group accomplished upon arrival.

Around 1887, Amos Throop, a self-made Chicago businessman and politician, began traveling to Southern California. Throop was in his seventies and still full of life and adventure. He and his wife bought and sold farmland in Los Angeles before finally settling in the Pasadena area. And Throop instantly fell in love with his newly adopted city and set out to leave his mark. As a former Chicago city treasurer, Amos had famously secured financing from NYC to rebuild his hometown after the Great Chicago Fire. Many years later (and after having lost two runs for Mayor in Chicago), his leadership skills prevailed—he was elected the third mayor of Pasadena, a job he coveted and took very seriously.

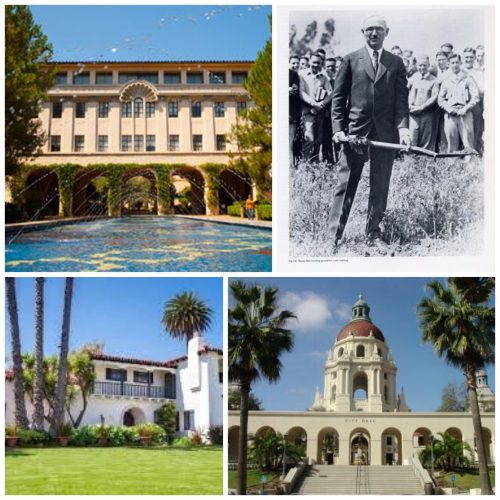

He saw the potential for a Great Western City, desiring nothing less than perfection. By far, his largest contribution to Pasadena came in 1891, when he founded Throop University, later renamed Caltech in 1920. Caltech’s first PhD was awarded that same year to Roscoe Dickinson in chemistry, establishing it as one of America’s great universities. Throop, previously a businessman, was 80 years old when he founded the University. Today, Caltech is highly regarded as one of the world’s leading scientific institutions.

Although Throop died shortly after the school’s opening, he was a leading visionary brimming with educational and civic ideas. In ten short years he accomplished a lifetime’s work in Pasadena, leaving the city with one of the jewels in her crown. His story reminds us all that our work is never done, and our ability to create and maintain change is not tied to our youth, but rather our passions.

Following the path of Throop was Myron H. Hunt. Born in the East, Hunt was raised in Chicago and educated at Northwestern and MIT. He opened his own architectural firm in Chicago in 1897 and shared office space for a few years with several famous architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright. However, Hunt’s young wife suffered from tuberculosis, thrusting the Hunts from Chicago to sunny Pasadena in 1903.

Upon arrival, he and his wife settled in an affluent area of Pasadena with prominent neighbors that included the Procter & Gamble heirs, David Berry and Mary Huggins Gamble; painters Alice and Freida Ludovici; and fellow architect Charles Sumner Greene. Inspiration and beauty were everywhere, providing Hunt with the energy to design an avant-garde type of building for his new hometown. Hunt immediately instilled a new level of academicism to the area’s building boom, setting off one of the greatest architectural movements in the history of Southern California. He leveraged his never-ending creative side, drawing deeply upon his early travels to Italy (and study of Renaissance buildings) to construct a signature style of architecture unique to Pasadena and Los Angeles, highly regarded worldwide.

Today, most of his 500 buildings still stand and include the Caltech, Pomona, and Occidental College campuses, the Huntington Library, Pasadena Public Library, the Rose Bowl, the exclusive Valley Hunt Club (the club sponsored the first Rose Parade to promote Pasadena as a warm-weather destination), major aspects of the Hollywood Bowl, Mount Wilson Observatory, the Huntington Hotel (now The Langham), and many of the most impressive Mediterranean-Spanish revival homes in Pasadena and the Southland. He also designed Polytechnic, the school all of my siblings and I attended, as an extension of Caltech and a place for professors’ children to be educated. Imagine a group of Spanish buildings housed around courtyards with fields that include views of the mountains—this was the setting for my 14 years of education, and it is nothing less than stunning.

All of this from a Chicagoan who had a penchant for tweed and who hailed from the vast cold plains. His greatness was in the detail and simple but tasteful grandeur of everything he built, a gift to Pasadena that has withstood earthquakes and change, and still draws awe in 2016.

The move west also included women. One in particular brought feminist leadership and views of equality straight from Chicago to the Southland. Heiress Kate Crane Gartz became one of Pasadena’s leading visionaries. The daughter of Richard Crane, founder of Crane Plumbing, Gartz came to Pasadena around 1908 with her family in tow, following the tragic death of two of her young daughters. The mother and wife quickly became a leader in the socialist movement (even nicknamed a Millionaire Socialist by some) and a major philanthropist, establishing the Pasadena Playhouse, Pasadena Civil League, and the American Civil Liberties Union. She also held famous salons in her home, with participation from such notables as Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, and Upton Sinclair. It is often reported that she personally financed many of Sinclair’s works.

Her lifelong interest in socialism and international politics helped establish Pasadena as a city of tolerance and acceptance. Through her courage and voice, Pasadena evolved into a place of privilege for all, not just a few. Although she never left her own social class, she worked diligently to never leave anyone behind. Her influence extinguished the “old” ideas of how women with her background were supposed to behave, installing a conscience for the wealthy newbies arriving in Pasadena from the East and Midwest. These liberal influences can still be felt in Pasadena today but live in harmony with conservative views.

Gartz adopted many of her ideals from her parents, and as a testament of her love for them, installed them into her daily life in Pasadena. As a woman, she opened her heart and soul to the meek, wrongly accused, and the underrepresented. She fought for justice, ruffling a few feathers along the way. At the end of the day, she was a strong, solid Midwesterner who helped cultivate the current culture of Pasadena, making her work immeasurable.

Not to be left behind in the cold, internationally renowned astronomer George E. Hale also arrived in Pasadena in 1903. Hale quickly began his work in astronomy at an observatory on top of Mt. Wilson, overlooking Pasadena. Having stemmed from a wealthy, sophisticated Chicago family—his father, William Hale, made his fortune selling Hydraulic elevators—Hale realized the potential for a rich arts scene in Pasadena, thus investing his free time and efforts in the founding of the Pasadena Music and Art Association, an organization which led the way for bringing well known musicians and the Los Angeles Philharmonic to Pasadena.

Not content with his civic involvement, in 1922 he convinced the City Board to hire the Chicago firm of Bennett, Parson & Frost to make a masterplan for Pasadena and create the “Athens of the West.” Hale had a vision of what the playground to the wealthy could look like and with a bit of prompting he set the wheels in motion for the beautification of Pasadena. The Pasadena Civic Center, City Hall, and the Library were all inspired from Chicago’s White City, and they all stand today as testaments to the unwavering good taste and long-term visions of Hale.

He went on to discover some of astronomy’s greatest advancements and made significant contributions to the expansion of Caltech, even establishing his own observatory there. Beyond this, he will be forever known as an early tastemaker of Pasadena. His mark is everywhere, including in many of the movies we view, with City Hall holding a starring role.

Of course, there were others who arrived from Chicago and left their mark on Pasadena. But the collective stories of these four individuals are what make them special, inspiring each of us to achieve a generosity of spirit that defines a life well lived. They easily could have landed and simply enjoyed the good weather; plenty of their friends did just that. Instead, they choose to invest their talents, resources, and time towards molding Pasadena into a city for future generations.

Today, Pasadena is replete with rich architecture, world-class educational institutions, and a way of life unique to the area. No one leaves Pasadena without a little awe and inspiration. If you happen to visit on a clear day in January, with snow covered peaks in the background, you may decree that these four Chicagoans had the right idea. I know that is the time of year I always say, “Time to move home,” but then I arrive back to our magnificent city and see I have the best of both worlds.