In a World of 20th Century Legends

Archie and President Kennedy

By Megan McKinney

When Archie and Ada MacLeish returned to America from Paris and the South of France in 1928—following five years in the tight little circle of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Gerald and Sara Murphy, the Ernest Hemingways and Pablo Picassos—with others, including the John Dos Passos, the Cole Porters, Fernand Léger, Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker—the shared limelight would not dim.

The MacLeishes began looking for a permanent country home in the East, and their American friends were aware of this, coming to them with news of this house or that one—but nothing was quite right. One day Louise Bryant Bullitt was riding her horse in the area around Conway, Massachusetts and saw the perfect farmhouse, surrounded by more than 300 acres of rolling green property. You may recall that Louise was married to William Christian Bullitt, the first U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and U.S. ambassador to France during World War II.

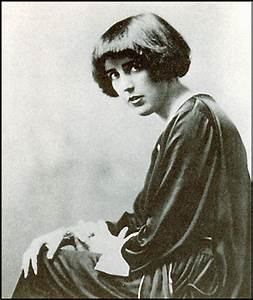

Louise Bullitt

Previously Louise had been lover, then wife, of the writer/communist John Reed, about whom the 1981 Warren Beatty film Reds was centered. She was portrayed in the film by Diane Keaton, Reed by Beatty, and another of Louise’s lovers, playwright Eugene O’Neill, by Jack Nicolson.

Diane Keaton as Louise Bullitt, with Jack Nicolson and Warren Beatty in the film Reds.

A few days after Louise’s discovery of the property, Archie and Ada, accompanied by the Bullitts, scaled the empty Conway farmhouse exterior and peered into second floor windows, eyeing spacious bedrooms with large fireplaces. It was perfect—an ideal place to live and to write for the next half century or more, they bought the property and named it Uphill Farm. Archie’s father, president of Carson, Pirie Scott & Company, had died that year, leaving Archie his stock in the great department store, with dividends that would provide needed income. The house and leisure time for writing were now Archie’s to enjoy. (It’s interesting that Marshall Field, who had been president of Chicago’s other major department store, a few blocks north on State Street, was born on a neighboring Conway farm, from which he left as quickly as he could get away.)

Henry R. Luce during his Yale years.

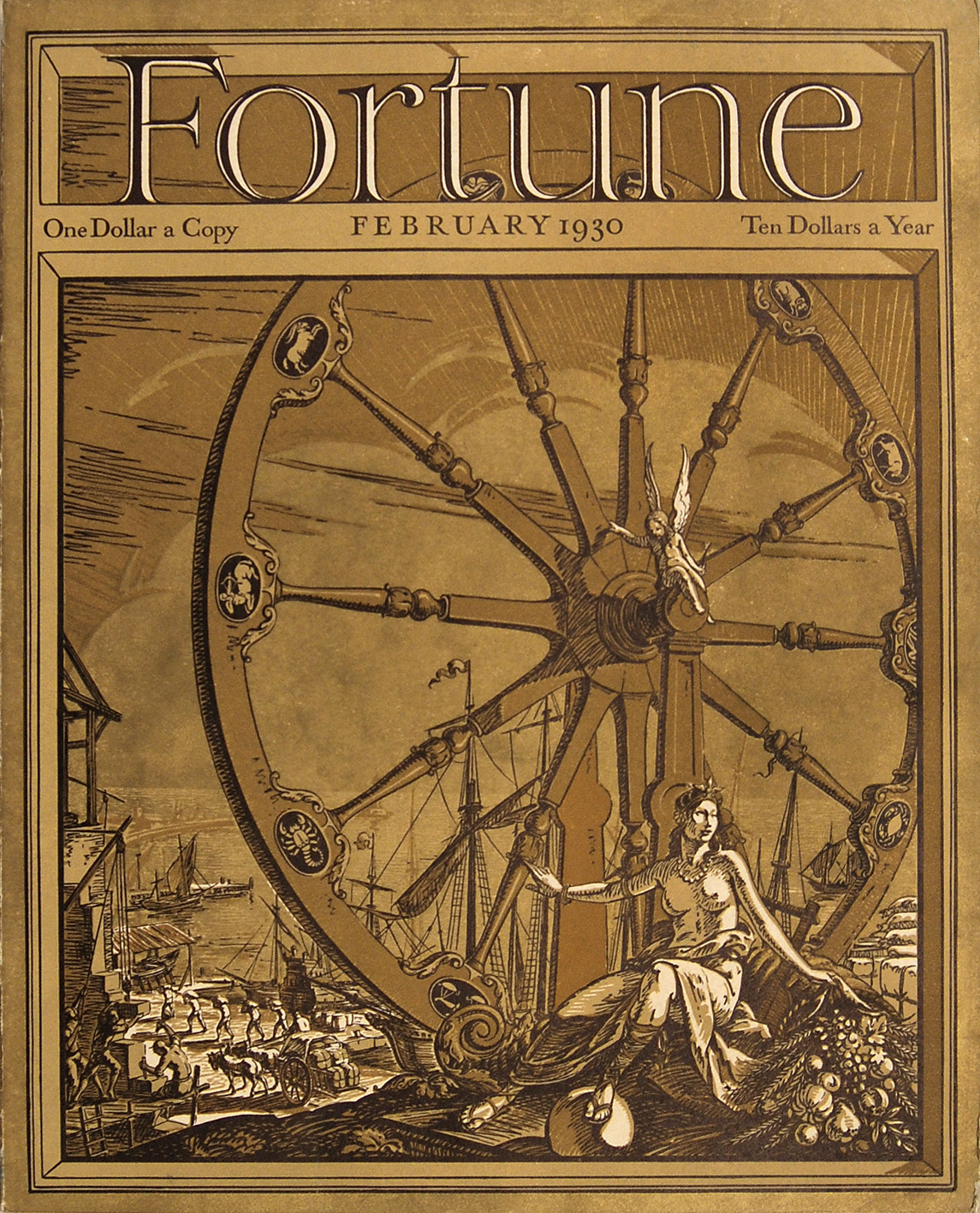

Then came October 1929 and the Stock Market Crash, which changed so many lives and suddenly made paid work necessary for Archie. Oddly, this was the moment Time Inc. magnate Henry Luce—Harry to his friends and colleagues—chose to launch Fortune, a rich man’s magazine; however, amazingly, it was one of the few stable places to work during the Depression. The scary, self-important Luce—a man who quickly and almost completely wrote his Time magazine co-founding partner, Briton Hadden, out of the history books—came close to worshiping Archie. For years, Harry, who had been four years behind Archie at both Hotchkiss and Yale, had been in awe of his predecessor, an athletic, academic and social hero at both. He was also a fellow Bonesman. So, for Archie, it was a cushy—and extremely interesting—position, with the mighty mogul deferring to his employee rather than the opposite.

From its first issue in February 1930 until 1938, Archie worked as a Fortune writer and editor, both from the Conway farm and on fascinating assignments throughout the United States, England, France and even Asia.

There was time, however, for Archie to continue his work as a major poet, a field in which he had become one of the most important of his time globally. Here he is with Robert Frost. Possibly Archie’s closest friend was Mark Van Doren, American poet, writer, critic and esteemed scholar and professor of English at Columbia University.

Archie in cap with Mark Van Doren, who was best known for a short time as the embarrassed father of fixed quiz show winner Charles Van Doren.

Those living in New York on Friday morning, December 12, 1958, an era in which Broadway was alive with great theater, may still remember that—because of a citywide newspaper strike—play reviews were being read on radio and television. All that early Friday morning, listeners and viewers were galvanized by readings of Brooks Atkinson’s dazzling New York Times review of a hit play from the previous evening.

“One of the memorable works of the century as verse, as drama and as spiritual inquiry” were Mr. Atkinson’s words about J.B. written by Archibald MacLeish, which had opened at the ANTA Theatre the night before. Any literate man or woman who had not been aware of Archie previously became so that morning. They were joined by the rest of America.

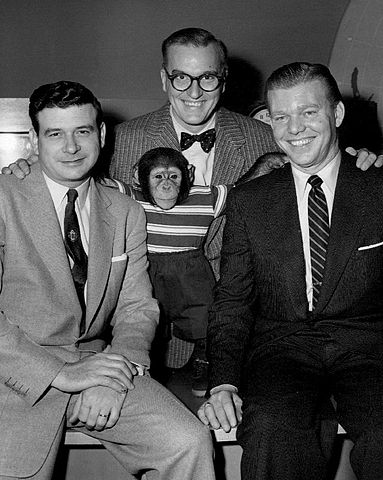

“Everyone” in New York during the midcentury began the day with Dave Garroway’s Today Show. It was where the news broke—particularly during the city’s frequent newspaper strikes. Dave, center with resident chimp, J. Fred Muggs, is bracketed by other regulars Frank Blair, left, and Jack Lescoulie.

Archie had been up all night following the J.B opening and had not heard the Atkinson review; therefore, he had no idea whether his brilliant—but somewhat pretentious drama—was a smash or a turkey with the critics. The sun was not yet up when walked into the NBC studio as the Today Show‘s opening guest that morning. Following the opening pleasantries with Garroway and the others, the Atkinson review was read on the show by Frank Blair. The exhausted Archie, hearing it for the first time, suddenly thought he “was going to weep out of a mixture of fatigue and joy.’’ No wonder. It was possibly the greatest rave in the long career of the hypercritical Brooks Atkinson.

Almost immediately, lines began forming, literally around-the-block, outside the ANTA Theatre and before the day was over, the show was a sell-out for months to come.

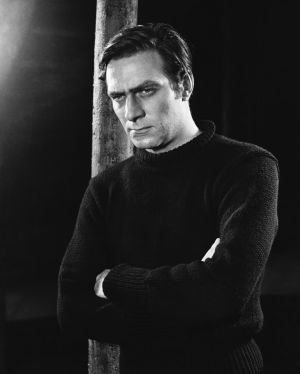

Christopher Plummer in costume for his role of the Devil in J.B.

J.B. was not a fun evening at the theater. Directed by Elia Kazan, it was written in verse. Furthermore, it was an updated story of the Biblical Job, over whom there was a struggle for his soul between God and the Devil. J.B/Job was portrayed by the convivial Pat Hingle. Raymond Massey played the role of God, and Lucifer, by Christopher Plummer. The latter two actors’ roles should have been reversed. Plummer was not only superb on stage but also a delight as a human being. The opposite was true of Massey, regarded as “nearly disastrous” in his role of Mr. Zuss (God). “A monument of egotism in a field where everybody is an egotist,” said Archie, who “learned to detest him.”

By the time Archie reached high middle age, there was possibly not a world-famous individual who wasn’t a friend. And his years at Fortune—in which he produced countless in-depth features on some of the most powerful men and women in the Western world—had intensified existing relationships, such as his cozy friendship with President Franklin Roosevelt.

In 1939, “The President decided I wanted to be Librarian of Congress,” remembered MacLeish, who was further urged by his close friend Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter to accept the position. He accepted and held the distinguished position until the end of 1944, when he was named Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs.

In 1949, MacLeish was recruited as Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University, a position he held until his retirement in 1962. “You have to have a writer who can write before you can teach him how.” George Plimpton below was among the writers who presumably benefited from gaining a position as one of 12 students in each term’s class.

When Archie finally had time to write poetry without having to squeeze it in between other activities, it had become more difficult to summon the genius he had so carefully nourished. And it became easier and quite pleasant to slip back into memories of earlier times, of which he had many.

In March 1982, he entered Massachusetts General Hospital for exploratory surgery and then surgery for an abdominal obstruction. He was still in the hospital when he contracted pneumonia, a condition which had become treatable but from which he died on April 20.

Archibald was then not quite 90 years old, a goal he would have reached 17 days later.

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl