Daniel Burnham’s Brilliant Partner

John Wellborn Root’s unforgettable style in The Rookery.

By Megan McKinney

John Wellborn Root was a brilliant, original and thoroughly delightful man. Although he was clearly among the greatest architects in Chicago history, his talents swept in every direction throughout the visual arts and music. He sang before he talked, soon out-played his piano teacher and might easily have moved from drafting table to concert stage. But his greatest gift was charm; he thoroughly captivated everyone he met.

Credit: The Art Institute of Chicago

Credit: The Art Institute of Chicago

One of the most delightful men in the Chicago of his time.

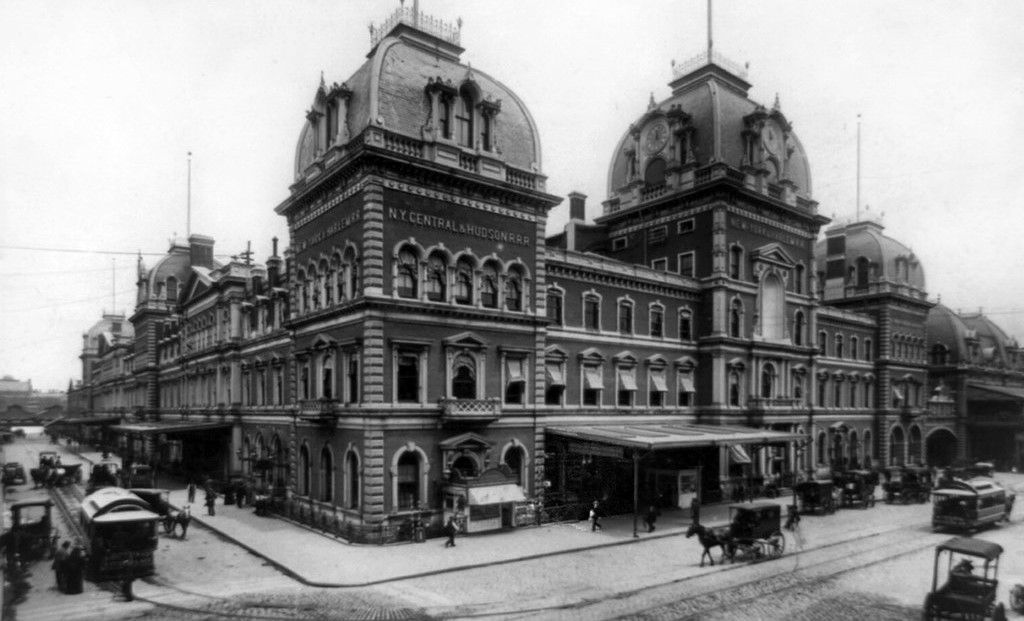

The United States was still without architectural schools in the 1860’s, thus New York University’s undergraduate civil engineering program was John Root’s foundation. After graduating from NYU with honors in 1866, he was apprenticed to architect James Renwick, Jr., designer of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and, while still in New York, he participated in building the 1871 Grand Central Terminal.

The first of New York’s three Grand Central Terminals

Among the many New Yorkers who were charmed by Root was architect Peter B. Wight, who marveled at John’s original designs as well as his personal charisma. Wight, who moved out to Chicago and established the firm Carter, Drake and Wight, soon summoned Root to join the company. Another young architect, who had recently been hired, was Daniel Hudson Burnham and the two became immediate friends.

The young Daniel Burnham.

The architectural brilliance of both Root and Burnham quickly emerged, each with talents that balanced the other. Throughout a formal partnership that began in 1873 and would last until1891, Burnham tended to be the organizer and Root the designer—but not always. Any company launching in 1873, the year of an economic panic, was in for a bumpy beginning. The two scraped by “with a couple of pencils, a piece of rubber…and one stick of India-ink.” But the following year a commission arrived that transformed both the future of their firm and the remainder of Daniel Burnham’s life.

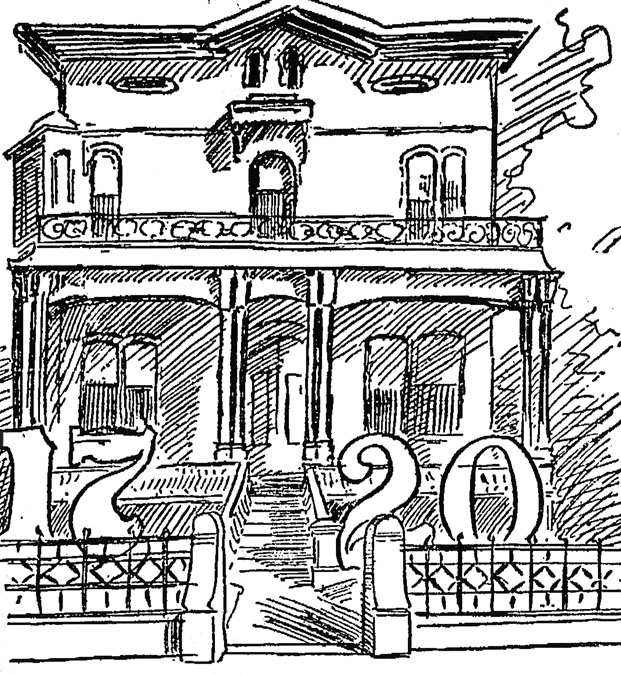

The three-and-a-half story mansion Burnham & Root designed for stockyards magnate John B. Sherman at 2100 South Prairie Avenue was the embodiment of the house virtually every other Chicago tycoon of 1874 wished to own and soon a torrent of residential commissions were surging in. But there was more. Sherman’s daughter Margaret began visiting the site during construction and Daniel made a point of being there when she arrived. What started as an intense mutual attraction soon grew into a life-long love affair; they married in early 1876.

Credit: Glessner House

Virtually the same romantic story was repeated, but with a tragic ending when, during the construction of the house Burnham & Root designed for James M. Walker, John fell in love with Walker’s daughter, Mary Louise. In 1880 they too married and moved into the new house at 1720 South Prairie Avenue along with her parents. Tragically, Mary Louise, 21, died of tuberculosis six weeks after the wedding.

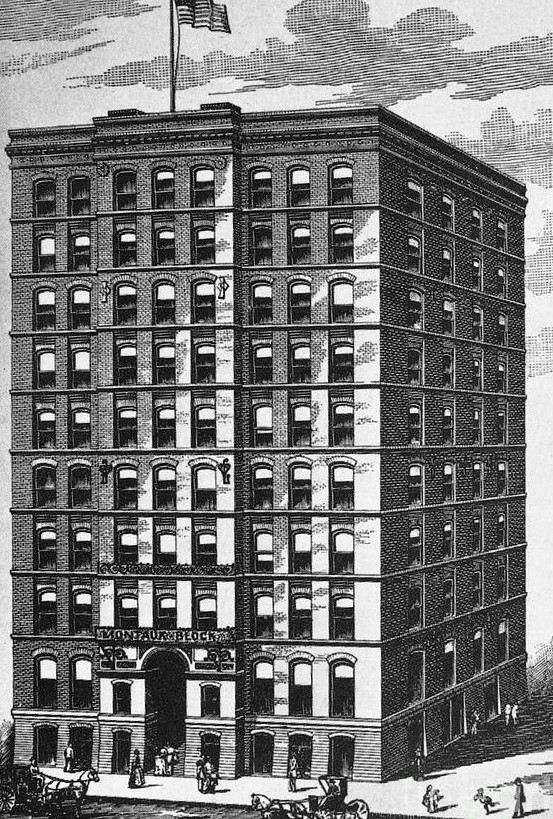

The previous year, 1879, John had met Owen Aldis at local reception. Aldis, a highly sophisticated, Yale-educated Vermont native, had moved out to Chicago and become a powerful real estate lawyer with strong Eastern connections. As usual, the immense Root charm, along with his brilliance, overwhelmed the one he was meeting. “No other man ever impressed me so quickly and so deeply,” Aldis later remembered. The two wandered off to a side room and talked until the early morning hours. Architecture was never mentioned and John was unaware that Owen represented the Massachusetts investor Peter Brooks, who, with his brother, Shepherd, had been financing Chicago buildings from the 1860’s. The next day Aldis brought Burnham & Root a commission to design the Grannis Block, a seven-story office building on property owned by Peter Brooks on Dearborn Street.

The Grannis Block.

The red brick and terra cotta Grannis Block, was followed by the Montauk Block, about which architect Thomas Tallmadge uttered his often quoted remark, “What Chartres was to the Gothic cathedral, the Montauk Block was to the high commercial building.”

The legendary Montauk Block.

New inventions were rapidly expanding “the high commercial building” industry in downtown Chicago. Passenger elevators created the glamorous experience of soaring to the heights of these buildings, and the telephone made it possible to move the management portion of a business away from its production portion. Soon Pullman, Armour, and the other great tycoons were transferring their own offices and those of their top executives downtown to be close to each other and to the Chicago Club, where they lunched at noon and gathered again for poker at the end of the day. There was no need for owners to be located in the stockyards or far flung factories when their production centers were but seconds away by telephone.

Yet, throughout the area we now term the Loop, there remained the challenge of securing skyscraper foundations in the soft, moist shifting earth. Root approached the challenge with his customary belief that just because a solution had not been found, it was not attainable. He focused his keen, trained engineering mind on the problem for less than two days and developed the floating raft system. The interlaced steel beams created a foundation for tall buildings that would not sink in Chicago’s marshy soil. Root’s first use of this revolutionary system was for the Montauk in 1882.

Harriet Monroe.

Harriet Monroe.

In 1882, John married Dora Monroe, sister of Poetry magazine founder Harriet Monroe, author of the 1896 biography John Wellborn Root: A Study of His Life and Work. John and Dora’s son, John Wellborn Root, Jr., would become an important architect of the Art Deco period, during which he collaborated in the designs of some of Chicago’s great circa 1929 landmarks, including the Daily News and Palmolive Buildings and 333 North Michigan Avenue. But that is a story for another day.

1310 Astor Street, center, today.

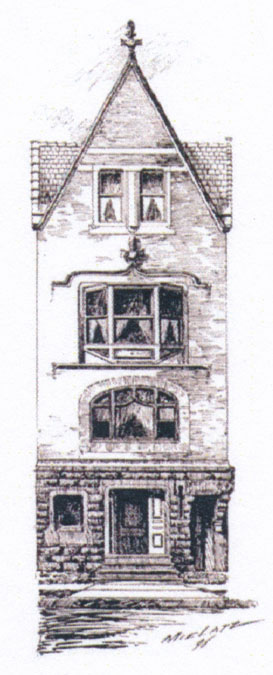

In 1888, the senior Root designed a house for his little family at 56 Astor Street, now 1310 Astor Street. Through 18 years and 300 buildings, the firm Burnham & Root had prospered, growing to be one of—if not—the greatest, of the city’s illustrious firms of the Chicago School. Then, suddenly, shockingly, everything changed.

This is the way the Chicago Tribune told the heartbreaking story on January 16, 1891.

“Chicago will be shocked at the news of the untimely death of John W. Root, easily its most distinguished designing architect, if indeed he had his superior in the whole country. In the prime of his life, his vigor, and his usefulness; in the midst of his invaluable services to the World’s Columbian Exposition, he seemed to be the man of all others who would be sure to continue for many a day one of its most esteemed and beloved citizens. In the flower of his days pneumonia at 56 Astor Street has suddenly ended his life, as it has during late years ended the lives of so many men young and strong like him. Less than a week ago he was in the best of health. Saturday he took a Turkish bath and later at his own house thoughtlessly stepped into the street to hand a friend to her carriage, becoming slightly chilled in so doing. During Sunday he received at his hospitable home a visit from the Eastern architects visiting the scene of the World’s Fair, and that night he was seized with a severe chill, which proved the beginning of a fatal illness. Even as late as noon of that day of his death he seemed in a fair way of recovery, but death came suddenly last evening.”

56 Astor Street in 1888.

56 Astor Street in 1888.

Daniel Burnham had been pacing the floor of Root’s house, waiting for each update from the doctor. It has been said that when the horrifying report arrived, Burnham was heard to respond “Damn! Damn! Damn!” In his extraordinary book City of the Century, Donald L. Miller, offers an extended and more intimate picture of the Root house on the night of January 15, 1891.

One of Harriet Monroe’s aunts secretly watched from the high corner of the stairway as Burnham paced the living room, alone, between intervals of restless sleep on the couch, punching the air with his fist and talking to himself in low, despairing tones. “I have worked, I have schemed and dreamed to make us the greatest architects in the world—I have made him see it and kept him at it—and now he dies—Damn! Damn! Damn!”

Subsequent segments of Classic Chicago Publisher Megan McKinney’s Great Architects will explore the life and career of Daniel Hudson Burnham, who would become director of works for the World’s Columbian Exposition and the great urban planner of his era.

Edited by Amanda K O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl