Augusta’s Kitchen

By Francesco Bianchini

If Catherine de’Medici introduced the etiquette, customs, and flavors of civilized Tuscany to the French court, it is curious that–despite the fact that my grandmother Margherita was from Piedmont and my mother originally from Burgundy–neither of them succeeded in changing the habits of our local cooks. That’s the way we’ve always done it, they would say, cutting short any discussion.

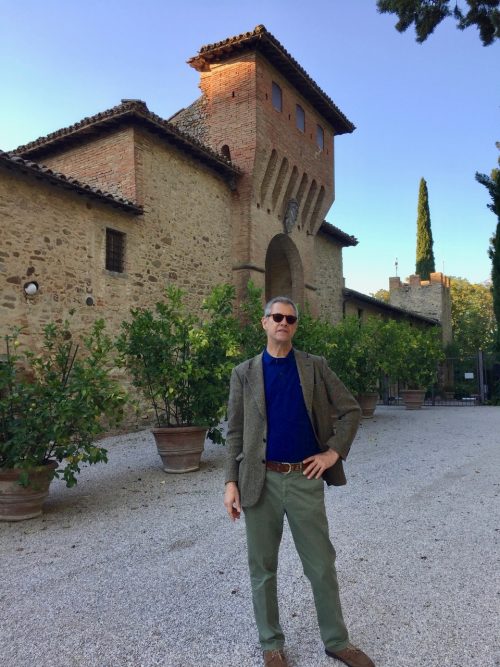

An areal view of the village of Collevalenza, central to my Umbrian childhood. In the foreground the castellated walls and the garden, my ancestral home.

Augusta, the cook during my family’s happiest years, was stubbornly opposed to any change or embellishment. It was from her that I learned something about cooking. To wit, how to prepare two mainstays of many of our regional dishes: soffritto and sugo finto. In the former, crushed garlic and chopped onion are lightly sautéd in olive oil, with chili flakes, carrots, and celery. It all starts there. Sugo finto is so called because it has neither meat nor fish; nothing more than peeled and diced San Marzano tomatoes added to the soffritto. When finished, a handful of chopped fresh parsley is sprinkled on top.

A close-up of the eastern wing of the castle

The kitchen at Collevalenza

Coming home from school, I’d walk through the kitchen where Augusta’s sugo would be simmering so gently that it never splashed onto the stovetop; a thick and orangey sauce speckled with tiny dots of carrot and celery. Distracting Augusta with some pretext or other, I’d quickly dunk a slab of bread into the pan and sneak away. Sometimes she wouldn’t notice the knavery, so involved was she in her other arts, such as cutting rolls of her incomparably thin and translucent dough with regular, precise strokes. Augusta had an unusual knife with a curved blade under the handle on which her knuckles rested. She would slice the roll of pasta on the cutting board, sweeping the resulting strings aside with quick, rhythmic movements, pausing from time to time to untangle them lest they stick together. Her name for this pasta was picchiarelli even if most Umbrians called it strangozzi or strozzapreti, a term alluding to the local belief that clerics never miss a good meal; maybe they die of indigestion, but never from hunger.

The Sugo Thief

Augusta’s gnocchi were neither too soft nor too hard, neither too small nor too large, and their ridged surfaces hosted her tomato and porcini mushroom sauce admirably. One of my first attempts to reproduce her gnocchi was, without exaggeration, a disaster; a blow to my self-esteem. I was visiting a friend in his New York apartment and our dinner guest that evening was a famous American food editor. The sauce of fresh San Marzano tomatoes and porcini mushrooms (difficult to find even at Manhattan’s gourmet grocers), had simmered in the afternoon and was resting, concentrated and fragrant, waiting for a final shot of fire. I peeled the potatoes, drawing them directly out of the boiling water, and scalding my fingers–because that was Augusta’s recommended method. (There always seemed a touch of masochism in her lust for perfection; perhaps to discourage rivals.) At the moment of kneading the mashed potatoes and flour, however, the irreparable occurred. It was the fault of an egg, actually two, that in a moment of panic – because the mixture seemed too dry – I had added to the dough. Too late to undo the damage, I realized that the gnocchi were turning into rubbery projectiles. (Had they fallen to the kitchen floor, they would have ricocheted all the way to the dining room.)

Preparing the gnocchi (from https://mammaboom.com/en/gnocchi-di-patate/)

When Augusta reached retirement age, she left us, and thus began a fatal decline in the quality of household cooking, perceptible in the debasement of the famous sauces, increasingly watery and tasteless. I was still a boy when she retired, but I remember perfectly the dishes I’d grown accustomed to enjoying (which I never ate after her departure): sliced roast beef with its accompanying brown gravy; potatoes mashed into a fluffy cloud wafting a slight caramel odor; potatoes sliced as thin as coins, also meat and cheese croquettes, deep-fried, but with such dexterity that they were tender and covered with filigree crusts. Augusta’s croquettes were rather square in shape, which is why they were always called “pillows”.

Editor’s note: Classic Chicago Magazine is pleased to introduce to readers our new monthly contributor, Francesco Bianchini. Francesco is a true Renaissance Man: born in Rome, he grew up in Todi–one of the storied medieval hilltop towns of Umbria in central Italy. His studies took him to Pisa, Heidelberg, and Trieste where he graduated as an interpreter-translator. Fully trilingual, for thirty years Francesco has taught French at the University of Perugia. He and his partner Dan now spend most of the year in France having moved first to Paris in 2010 and subsequently to the beautiful Dordogne-Périgord region. For the past several years they have operated a small hotel de charme, Les Suites Sarladaises, in the heart of the medieval town of Sarlat.

Initially penned in Italian, his mother tongue, Francesco has agreed to share with us his translations of essays reflecting on a life well lived—and keenly observed. He takes seriously Shakespeare’s admonition in The Merry Wives of Windsor that ‘The world is your oyster,’ May his love of adventure and his desire to share quiet moments of insight and delight never cease.

As background to his monthly column, Francesco says: I hope that from time to time you will enjoy these short memoirs of my life in Italy, and of my travels here and there. They provide glimpses into what I now understand was a somewhat rarefied upbringing in Umbria and include my wanderings from that point on. I advocate thinking in circular time — arguing that creativity is a loop or a spiral; that memory is not linear, a straight line from point A to point B, but rather (as in the works of Proust or Woolf) small epiphanies of remembrance—of tastes, flavors and aromas that can transport me as far back as my childhood in Italy, then forward in time to encompass journeys and experiences I’ve had around the globe.