Glamorous Grandson Freddy

By Megan McKinney

Harvey men were stars; they were players in a real life mini-series that kept unfolding through the colorful last half of the 19th century and into the 20th. The dynasty’s next generation born-to-be-a-celebrity was Frederick Henry Harvey, a name too stuffy for the daredevil who would carry it.

Ford and Judy Harvey’s fearless, speed and danger chasing son, born in January 1896, soon acquired a nickname as energetic and dashing as the youngster himself; he would be known as “Freddy” for the rest of his life.

There was to be no Racine College for Ford Harvey’s son; Freddy was sent first to prep at the prestigious St. Mark’s School near Boston and on to Harvard.

St. Mark’s School

In April 1917, when the United States finally declared war on Germany, 21-year-old Freddy dropped out of his Harvard junior class to join a tiny group struggling to become named the U.S. Army Air Service, which it would in May 1918; there was not yet a United States Air Force and wouldn’t be for decades. The neophyte Air Service was all there was. But just look at its planes in action.

From a1918 lithograph of the Air Service in combat.

It was quite an era for the Harvey dynasty. The Air Service was a perfect fit for the intrepid Freddy Harvey and World War I pulled the great eating houses established by his grandfather out of their early 20th century doldrums. As trainloads of troops crisscrossed the nation, Fred Harvey was back in action to feed the tens of thousands of hungry doughboys devouring meals for which the War Department paid.

The young soldiers were crammed into eating houses at long tables or sometimes they simply received ample Fred Harvey bag lunches passed to them through train windows. They were also served hearty, no frills Fred Harvey meals in crowded troop train dining cars. The company had returned to the food service business—big time—even bringing former Harvey Girls out of retirement and into the depot eating houses.

Freddy was one of the earliest volunteers trained for air after the country joined the war. His flight training was a six month session at the Glenn Curtiss facility in Miami, Florida. Among those with him was the somewhat older Hiram Bingham, whose derring-do would later inspire the Indiana Jones character. It wouldn’t be long before many legendary aviators and other adventurous figures of the time would routinely be in and out of Freddy’s life.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Freddy was commissioned as lieutenant and “put in charge” of the 27th Aero Squadron, which joined the British Royal Flying Corps in Toronto, where the two would train together. Next it was Scott Field near St. Louis where Freddy would be “assistant officer in charge.” Then on to Camp Taliaferro in Fort Worth, Texas, “where he became a legendary instructor.” He was promoted to captain and received orders to leave for Europe in September 1918, a departure delayed for a tonsillectomy, a common procedure that year as a precaution against the Spanish flu raging throughout the world, much as coronavirus is today.

Freddy sailed for France in October, arriving a scant month before the war’s end, and he was back in New York in February. Rather than returning to Harvard, his father wanted him to begin training for his future role as head of Fred Harvey. Shadowing various company executives was necessary but comparatively dull after the Air Service years of being “in charge” here and there. However, the grand period of aviation would soon begin and Freddy would be a part of it.

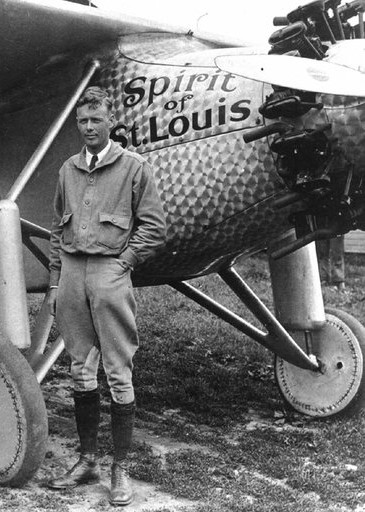

On May 21, 1927 at 10:24 p.m. an obscure St. Louis air mail pilot, Charles A. Lindbergh, landed at Le Bourget field in Paris and instantly became the most famous man in the world. Freddy had known the straight arrow, no nonsense Lindbergh from the young pilot’s stint at a 1925 reserve officers camp in Kansas City. He’d also known Lindbergh’s wealthy Spirit of St. Louis backers, including prominent stockbroker Harry French Knight, for many years. The Lindbergh backers’ St. Louis Flying Club, of which Knight was president, was similar to Freddy’s flying club in Kansas City— both part of a loosely knit national aviation fraternity. The first solo nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris would bring unprecedented fame and glory not only to the individual who made the crossing but also to his city, and St. Louis had wanted it badly.

During the months following Lindbergh’s historic flight, the Lone Eagle flew throughout the nation, making personal appearances, riding in parades, attending banquets and giving speeches, all in the interest of promoting aviation. Much of this activity was underwritten by mining and smelting heir Harry Guggenheim to the tune of three million 1927 dollars from the immense family coffers.

In addition to parades, banquets and speeches, Lindy was spending time both in air and on the ground with Freddy Harvey and Harry Knight, discussing flights, planes and aviation in general. But at the same time they were working on a mutual business interest, a passenger service that would marry air and rail, trimming 24 hours from the current three-day cross-country train journey.

One of TAT’s 14-passenger planes.

Spanning the nation entirely by air was out of the question; passenger planes were without lights, as were airfields. Therefore the plan was to design a cross-country itinerary that would unite alternate segments of day air travel with overnight train service. The result was Transcontinental Air Transport, or TAT, a project that fired the imaginations of nationally known figures of the late 1920’s. Those involved, along with Freddy Harvey, Harry Knight and Charles Lindbergh, were Wilbur and Orville Wright, Henry Ford, whose motors powered the planes, aircraft manufacturer Glenn Curtiss, and Clement M. Keys, president of Curtiss Aeroplane and Motors Company.

Eugene Vidal, father of Gore Vidal, and close friend of Amelia Earhart, became TAT general manager. Gene Vidal’s relationship with the renowned aviatrix teetered on the edge of romance and was probably consummated, according to his son, who hoped she would become his stepmother.

TAT manager Gene Vidal and Amelia Earhart.

Pennsylvania Railroad and the Santa Fe were the rail lines that joined TAT airplanes in the project; however, they would become redundant when planes began flying at night. That is when TAT morphed into TWA.

Freddy had followed his father, Ford, in making a marriage that, at least to onlookers, appeared to be idyllic. When he was 26, Freddy fell in love with the beautiful 16 year-old Betty Drage, who—while not as privileged as he—was scarcely from a background without means or glamour. Her socialite mother, Lucy Drage, was a Kansas City heiress known for her exquisite taste and Betty’s polo-playing English father, Frank Drage, was a Boer War veteran and former British Royal Horse Guard officer.

Photo Credit: Appetite for America by Stephen Fried

Betty Drage Harvey.

In the early fall of 1922, Freddy and the then 17-year-old Betty were married and, following a lengthy European honeymoon, returned to a new, beautifully decorated, house, which Ford had ordered built for them near his own.

Within four years the two generations of Harvey golden couples–Ford and Judy and Freddy and Betty—would begin to face a series of tragedies. In July 1926, during a Santa Fe vacation with her daughter, Kitty, Judy suffered a devastating stroke. Although she survived for several days, during which Freddy, Ford and their Kansas City doctor, were able to travel to her New Mexico bedside, Judy died. She was 59.

Next was Ford. A decade after the infamous Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, there was another less severe epidemic of influenza raging. One of its victims was 62-year-old Ford Harvey. Both Judy and Ford died with unexpected suddenness and at ages we would consider tragically young; however, less than a decade later, a genuinely shocking double tragedy occurred.

Freddy’s dashing new Beechcraft Staggerwing.

On April 16, 1936, Betty arrived in New York from England on the S.S. Manhattan. Freddy was there to greet her on the pier and, during the next four days, they shopped, met with New York friends and enjoyed the great city of the 1930s. On Sunday morning, the couple took off for Kansas City in Freddy’s new Beechcraft Staggerwing. As they neared the dreaded Allegheny Mountains, conditions became icing and they decided to stop for lunch at the Duncansville Airport. Although he was warned of dangerous conditions, Freddy elected to continue the trip home after lunch.

Almost immediately, they were engulfed in clouds, wings icing, and in the midst of true horror. The experienced pilot was unable to ascend to a height at which he would have visibility and an end to the icing. He attempted an emergency landing but lost control of the plane, which hit electrical wires and with devastating suddenness crashed into a mountainside, causing the newly refilled fuel tank to explode. Freddy and Betty had been airborne for 18 terrifying minutes.

At 2:18 pm on Sunday, April 19, 1936, when Freddy’s handsome Beechcraft Staggerwing crashed into the mountainside and plummeted to earth, the destiny of the Fred Harvey brand and all that went with it, shot with suddenness from the dynasty’s Ford Harvey branch to the family of Ford’s younger brother Byron Schermerhorn Harvey, and from Kansas City to Chicago. It would take a little time for it all to physically occur, but it would.

Byron Jr. and his wife, the former Kathleen Witcomb, with Byron III, representing second and third generation Chicago Harveys.

Byron Schermerhorn Harvey, who had been running the dining car portion of the company from Chicago since early in the century and carried the title president of Fred Harvey, was suddenly also patriarch of the clan, a family of delightful individuals who now have been enlivening Chicago for four generations, and growing.

Unburdened by operating Fred Harvey, which was acquired by Amfac, Inc. of Hawaii in 1971, they may be the enchanting subjects of a future dynasty series.

Publisher Megan McKinney’s Classic Chicago Dynasties series on Fred Harvey concludes with this segment.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl